It’s 11 p.m. on a Thursday in New York’s Greenwich Village, and Lucas Zelnick, MBA ’22, is on the mic. He’s already done sets at two other clubs in Lower Manhattan this June night. Now it’s his third and final set, this one at the famed Comedy Cellar, the launching pad for comedy legends Jon Stewart, Chris Rock, and Amy Schumer.

“I feel like everyone has their own reasons for not being religious. Personally, I’m not religious because I grew up rich, so I just never needed that excess hope,” he says, drawing a round of laughter. “How are you gonna be a religious rich kid? Like, ‘My dad bought me an apartment, so I’d like to thank god—thank god for private equity!’”

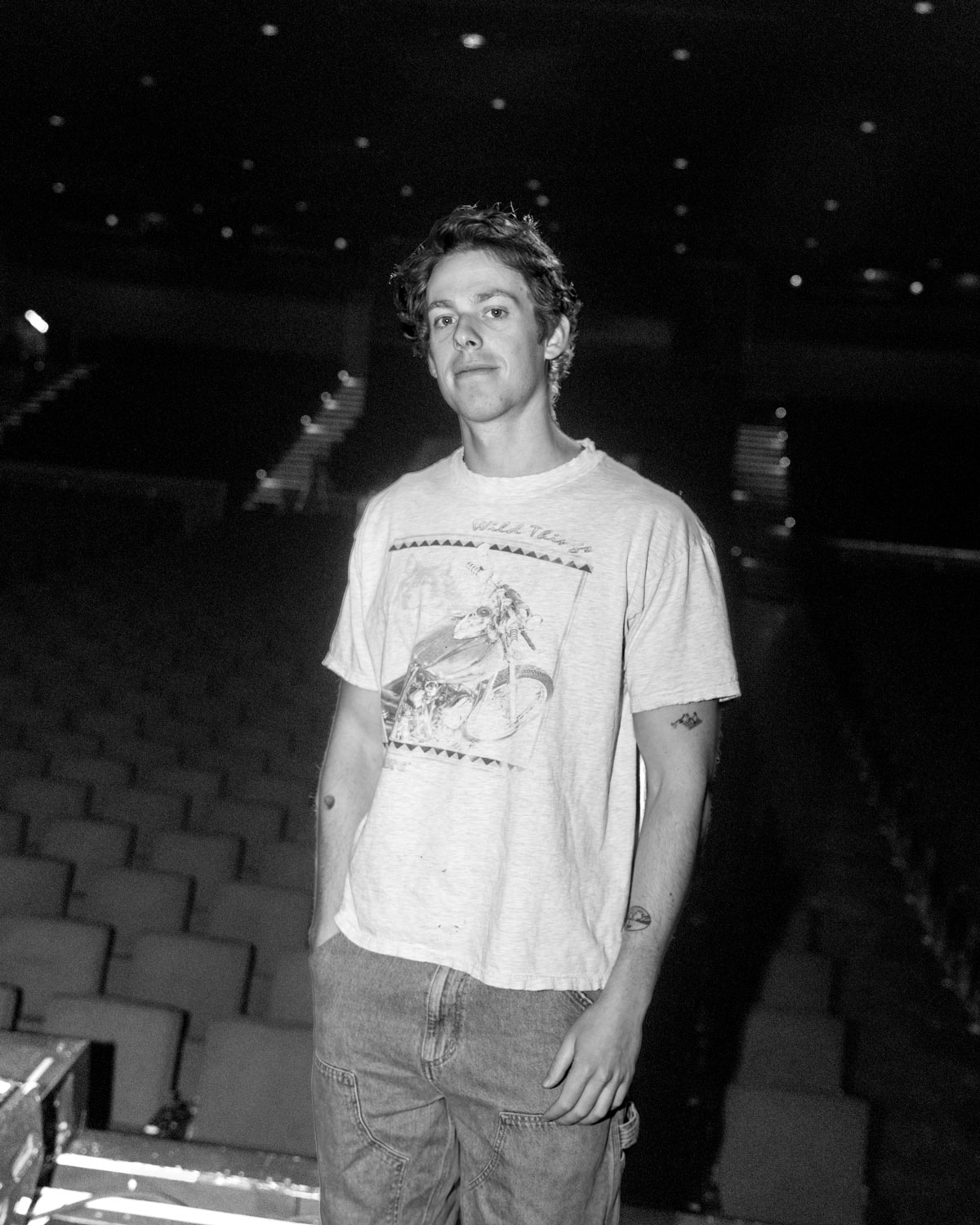

He is wearing his standard getup, a graphic tee and jeans, and holds the microphone loosely. Lights glint off his auburn hair. By all indications, this set has been going well. The audience, filling the dimly lit room, is laughing at Zelnick’s jokes and participating gamely in the give-and-take that is live performance.

But then, partway through his 15 minutes, a pair in the front row begins talking to each other, and not in a polite whisper. There was a time when he wouldn’t have known how to handle such an interruption. But today, he’s got experience on his side. He weighs his options, then confronts the talkers: “You have to stop having, like, a full-blown conversation.”

It’s been a whirlwind for Zelnick, 30, who, in six short years, has gone from non-comedian to having TikTok posts reach 10 million views. He first dipped his toe into stand-up in 2019, when he took a class filled with retirees in a performing arts space in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. (“The class was more, like, insane and lonely people than aspiring comedians,” he says.) It was the most immediate and structured way he thought he could try comedy without chickening out.

Zelnick grew up on the Upper East Side. His father founded a private equity firm, and when Zelnick went to undergrad at Williams College, he thought he’d go the business route too. After graduation in 2017, he worked in corporate strategy at Viacom. But it didn’t feel quite right. So, on the side, he tried improv—he’d always connected with people by trying to be funny. It turned out he wasn’t very good at improv. And that’s when he took that fateful stand-up class, and things began to click into place.

‘When doing new jokes, sometimes you walk all over the laughter. Then sometimes you pause and there’s nothing, and you’re like, Oh, no. That sucks for all of us!’

“I would describe my comedy as personal, with political and observational elements. I like to be silly, physical, and above all else, honest,” Zelnick says. “I find it easiest to write a joke if I feel like there’s a unique reason why I can say that. I start with myself and my own experience, so that when I say, ‘This is how the world works,’ the audience doesn’t go, ‘What do you know?’ Because I’m really saying, ‘This is how my section of the world works, and I hope you can relate to a couple pieces of that.’”

Ashley Gavin, a fellow comic and a mentor, says Zelnick is not interested in false premises or contrived twists. “He talks about his special needs sister. He talks about his wealthy family. He talks about things that many people would be like, ‘Oh, this is unpalatable. I shouldn’t talk about this.’ But he has no problem approaching it.”

A mere three weeks into developing his first set, he was asked by a family friend to perform at a hospital charity event. He probably should have said no, given that he still hadn’t performed for a crowd outside his comedy class, but that also meant he didn’t know how badly he could bomb.

“All the doctors there were doing jokes out of joke books, so all the jokes were like, ‘a priest walks into a bar’ or whatever,” Zelnick says. “Then I got up and was trying to do jokes about, like, having sex and stuff.” That material—which he now knows has its time and place—did not amuse the 500-person audience, among them Martha Stewart. He cut what was supposed to be a 10-minute set to four and ran off stage. “That was the first time I was like, ‘Oh, this is a hard job,’” he says.

In 2020, not yet fully committed to comedy and still thinking his future might be in business, he enrolled at the Graduate School of Business. The pandemic put his nascent performance career on hold, for a while. But the following summer, he returned to his native New York and, he says, “accidentally” co-founded Sesh Comedy Club on the Lower East Side. He’d only meant to rent a space with a friend for the summer to work out of and write scripts, but then they realized they could offset the rent by producing shows. And suddenly he was performing 14 times a week.

Zelnick sold Sesh after that summer, a decision made with the help of lessons from the GSB. “If I hadn’t taken Finance 201, I probably wouldn’t have understood how a company is valued, and that our club was worth selling,” he says. During the second year of his MBA, he was regularly going to class during the day, then performing in San Francisco at night. By then, he knew that this path was it.

Stand-up is an iterative process in which practice hones everything from a comic’s stage presence to a specific new joke. That’s why the schedule is nonstop. These days, from September to May, Zelnick tours the country, usually doing six hour-long shows to crowds of around 400 (and, so far, as big as 1,200) every weekend in locales ranging from Dallas and Seattle to Savannah, Ga. and Appleton, Wis. (He makes good use of his Delta Airlines Diamond benefits.) Summers are for writing and trying out new material nightly in short sets at the comedy clubs across New York City.

He jots down ideas on his phone as they come to him before crafting them into jokes worthy of the microphone. Then onstage they go, where he’s able to gauge audience reactions so he can progressively tweak them. Inevitably, that process includes bombing. “While creating a joke, you start to develop a sense for the timing, and that takes a while,” Zelnick says. “When doing new jokes, sometimes you walk all over the laughter. Then sometimes you pause and there’s nothing, and you’re like, ‘Oh, no. That sucks for all of us!’”

Bombing and uncooperative audiences are a fact of stand-up comedy, no matter your experience level. It’s just that now, Zelnick has developed a toolbox of potential ways out—that don’t include running off stage. “If I can kind of playfully get upset at the audience, because I think it will improve the condition of the set, I’ll do that. I could switch up the jokes I’m doing. I could pull out of a joke I’m doing if I feel like it’s not landing well or not as I intended, or I get interrupted. There are a lot of paths,” he says.

It’s one of those paths that has helped him build a large online following. Clips of his crowd work—when a comic interacts directly with the audience in an unscripted manner—have earned him half a million followers on Instagram and more than 58 million likes on TikTok.

“I give Lucas a lot of credit for, from early on in his career, being really confident in knowing that there will always be a light at the end of a tunnel of interaction. He’s not worried about how long he spends in that uncomfortable space, which can take some comics many years to learn,” Gavin says. “Another thing that takes many comics a long time to realize is to just point out the awkwardness that everyone’s feeling. Lucas had a good instinct for doing that almost immediately.”'

“I have a great deal of trust in myself that I can go ‘skydiving’ and build the parachute on the way down, because I know that I can summarize what I’m seeing in a way that feels emotionally accurate relatively quickly. And knowing that makes those moments really fun, because when it works, it feels like a magic trick,” Zelnick says. “Everyone’s like, ‘How the f— do you improvise on stage?’ And it’s like, well, how do you have a conversation? You’re improvising in a conversation, and you’re not worried about it.”

And so, at this Thursday night set with the chatty couple, Zelnick reaches into that toolbox. In this instance, he decides to engage. “Be funny,” one of the women shoots back. Ouch. He brings in the rest of the crowd to shift the energy: “I think I am. Clap if you think I’m funny!”

Cheers and applause—there’s no question most of the audience is on his side, and the interruption is quashed. And anyway, it’s just one set. Soon enough he’s out of there, satisfied with what he’s been able to give the audience.

“I feel like that was me handling that situation better now as a result of experience,” he said after the set, relaxing in the comedian’s hangout upstairs. “But it’s a fine line to walk. You want to be equal parts in control of the set but also responsive to what’s really happening with the audience. And the second that you think you’re better than the audience, the audience reminds you that there are more of them than there are of you.”

Evan Peng, ’22, is a contributing editor at Stanford. Email him at stanford.magazine@stanford.edu.