In 1925, the very concept of the Stanford Graduate School of Business needed to be explained to students via articles in the Stanford Daily. A quarter-century earlier, the teaching of business subjects had just found its way into schools. That education was highly vocational, a “natural outgrowth of the traditions carried over from the apprenticeship system, which had existed for centuries,” wrote author Neill Wilson in a 1930s overview of the GSB. The MBA itself still had that new-degree smell; it had only been established in 1908, at Harvard.

Thus were articles written and informational talks held to encourage undergrads to, one, consider getting an MBA; and two, not abandon the West for it. The fledgling school would teach not the how of business but the why. The Stanford business student would learn to “observe keenly, discriminate intelligently, to use his imagination profitably, to judge evidence correctly, and to concentrate,” wrote Wilson, Class of 1912. The business executive of tomorrow was “to be able to take a given business situation, and, by a process of straight thinking, arrive at a sound and practical solution.”

A century later, the MBA degree is solidly rooted in society. GSB alums have innovated, transformed, and founded, from Nike to Electronic Arts, Sun Microsystems to Capital One, Charles Schwab to Trader Joe’s. And the GSB’s vision—and influence—is decidedly global. Its motto is Change lives. Change organizations. Change the world. Here are a few of its signature moments and milestones over the past 100 years.

1920s

How the West Was Won

A strong economics department and some encouragement from a future U.S. president helped launch the Stanford Graduate School of Business in 1925. Herbert Hoover, Class of 1895, then the U.S. secretary of commerce and a member of the university’s Board of Trustees, advocated for the GSB. Willard Eugene Hotchkiss, PhD 1916, had helped found business schools at Northwestern and the University of Minnesota and was recruited to be the GSB’s first dean. The school was created with a simple goal: to give Stanford undergraduates an option to pursue graduate education in business on the Pacific Coast.

Willard Eugene Hotchkiss (Photo: Stanford News Service)

Willard Eugene Hotchkiss (Photo: Stanford News Service)

“Once in the East, many of these young people remain there and the West loses their services,” Hotchkiss told the Daily.

The school, first housed in the Quad’s Jordan Hall, opened its doors on October 1, 1925, with 16 students. Murray Shipley Wildman, head of the economics department at the time, was credited with helping lay the foundation for the GSB by tripling enrollment in the economics department between 1912 and 1920. The GSB graduated its first MBA class—two men, both of whom ultimately became ranchers—in 1927.

The University proposes to build a graduate school of the first rank in which young men and women may be trained for business leadership.

All About Interest

One of the GSB’s founding faculty members was professor of psychology Edward Strong Jr., an expert in vocational psychology. The work that would define his career became available shortly after the GSB opened: the Strong Interest Inventory, a questionnaire to help people determine their aptitude for certain careers—40 for men and 18 for women. “I’m not interested in financial success,” said Strong, who had helped assess soldiers’ suitability for Army roles during World War I. “I’m concerned with personal happiness.” In 1943, after analysis and follow-ups with test-takers, Strong concluded that interest was a better predictor of professional success than ability. Versions of the test are still used today, by the Myers-Briggs Company.

Christine Isabelle Ricker (Photo: Stanford News Service)

Christine Isabelle Ricker (Photo: Stanford News Service)

Dining in

The GSB graduated its first women—Helen Carpenter and Gertrude Benedict Lasher—in 1930. But the school’s first female matriculants, Etta Howes Handy and Christine Isabelle Ricker, arrived in 1926. Neither completed her graduate degree, but both made their careers at Stanford. Handy was director of the student union (now Old Union) and the university’s dining halls for eight years. She later authored two books, Furnishings and Equipment for Residence Halls and Ice Cream for Small Plants. Ricker succeeded Handy in those two roles, holding the positions for 28 years. Sterling Quad’s Ricker Dining is named for her.

$4o,ooo

to launch the GSB—about $730,000 today.

The GSB ‘had a specific aspiration that was consistent with Stanford’s regional nature at the time. Fast-forward a hundred years and the school, like the university, has become a national and global institution. People come from everywhere, and the amount of innovation and leadership that has come out of the GSB is extraordinary, world-changing.’

1930s

Jacob Hugh Jackson (Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries)

Jacob Hugh Jackson (Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries)

Invested

In 1931, accounting expert and GSB professor Jacob Hugh Jackson became the school’s second, and longest-serving, dean. He served through the Great Depression and World War II, and into the economic boom of the 1950s. During his 25-year tenure, he established a focus on “scientific management,” a theory centered on industrial efficiency and standardization (and often criticized for draining workers) that still reverberates in society today.

Main Quad to the History Corner (Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries)

Main Quad to the History Corner (Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries)

In 1937, the GSB relocated a few doors down the Main Quad to the History Corner. The school gained five classrooms—and left behind the wafting dogfish odor of its biology lab neighbor in Jordan Hall.

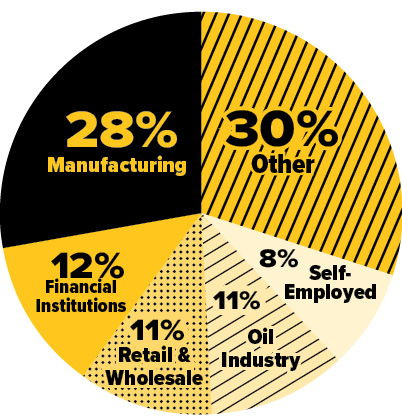

Manufacturing for the Win

79% Pacific Coast

The school’s first alumni employment and salary survey was published in 1939. In it, GSB professor Paul Holden showed that manufacturing work dominated and that graduates were indeed staying on the Pacific Coast.

We visualized ourselves in high-paying, responsible positions in a relatively short period of time. As matters turned out, we were rapidly deflated, and I suppose we were lucky to have stayed off the [Works Progress Administration] rolls during the ’30s.

1933

The Stanford GSB Library opens with 7,000 books.

1940s

War Arrives

In 1941, a few months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Stanford was doing what it could to prepare for the country’s possible entry into war. Eliot Mears, one of the GSB’s three pioneer professors, oversaw the university’s summer quarter in 1941 and noted the “greater seriousness evident in every aspect of university life.” (Mears, an expert in international trade, went on to join the War Shipping Administration the following year.)

At the GSB, efforts included expanding offerings so that students could complete graduation requirements as quickly as possible and “further the program of national defense.” After the attack on Pearl Harbor, typing and shorthand classes at the GSB were opened to undergrads as a “war-time training measure,” and, for a few years, the school offered a bachelor’s degree in business.

By 1942, the GSB was offering war-specific courses, including Occupational Hygiene in War Industries and Industrial Relations in War Industries, and had created an intensive, four-quarter graduate program that led to the degree of Industrial Administrator.

7

students in the MBA Class of 1944. Enrollment plummeted during World War II but surged afterward. In June 1947, the GSB celebrated 164 graduates—its largest class up to that point.

Behind the Scenes

Lillian Owen (Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries)

Lillian Owen (Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries)

In the summer of 1943, special certificates were offered to female students who sought employment in war industries. One of the women’s instructors, Lillian Owen, was the GSB’s executive secretary. The first female faculty members wouldn’t be hired until 1972, but Owen was, according to one report, “the person who really ran the school during its first two decades.”

1950s

Captains of Industry

It’s been more than four decades since the manufacturing industry ran on all cylinders in the United States. It peaked here in 1979, when the sector employed nearly 20 million people. But as a share of overall employment, manufacturing was highest in 1953, when 32 percent of the nation’s non-farm-employed people made their money making things.

The GSB was in manufacturing then as well, running an “industrial laboratory” out of two small rooms on campus. The lab, reportedly the only one of its kind at a business school, produced a limited run of new products each year (50 circular saws in 1950; 250 tiny motors in 1951). Some failed: A “food chopper” designed by a student had to be, well, chopped, after it was found to infringe on an existing patent. And there were supposed to be 500 motors in 1951, but material shortages forced the students to rev down production.

1,630

MBA degrees awarded in the GSB’s first 25 years. As of September 2024, 25,376 MBAs had been awarded, along with 14,477 PhD, MSx, and Stanford Executive Program degrees.

YELL, LEADER: Arbuckle directs football fans in a round of the Axe Cheer. (Photo: Chuck Painter/Stanford News Service)

YELL, LEADER: Arbuckle directs football fans in a round of the Axe Cheer. (Photo: Chuck Painter/Stanford News Service)

“If the private enterprise system as we know it is to survive, we must instill in our students attitudes that accept integrity, rooted in the bedrock of principle, as more important than operational competence.”

1960s

A Revolution

Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries

Photo: Special Collections & University Archives/Stanford Libraries

In 1959, a bombshell report by UC Berkeley’s Robert Gordon and GSB professor James Howell dropped into the world of university business education. The Gordon-Howell Report was sponsored by the Ford Foundation to improve business school education, and its economist authors argued for a more intellectually rigorous approach, drawing more from disciplines including economics, psychology, and statistics.

Howell profoundly changed how management education was taught around the world, inspiring greater emphasis on fundamental disciplines and on knowledge creation in the form of faculty research. His efforts are considered core in the GSB’s rise to national prominence. “It’s hard to imagine where Stanford Graduate School of Business would be today if not for the vision and work of Jim Howell,” said then-dean Levin in 2019. “He is considered one of a handful of catalysts responsible for the management revolution of the 1960s.”

Photo: Reprint Courtesy IBM Corporation ©2025

Photo: Reprint Courtesy IBM Corporation ©2025

“Many people foresee greater changes in the practice of management in the next 20 years than in the past 2,000, with the computer playing a catalytic role. Some view the anticipated changes with great enthusiasm for the efficiencies they will bring and the new vistas they will reveal. Others worry about what will happen to their jobs. Will some machine ‘displace’ them? Is their present skill obsolescent?”

1966

The GSB and Stanford Law School announce a joint LLB/MBA (now JD/MBA) degree. Today, the GSB also participates in five joint master’s programs, in education, public policy, computer science, electrical engineering, and environment and resources.

‘Touchy Feely’

Twelve students took Interpersonal Dynamics when it was first offered, in 1966. Over time, the elective course gained the nickname Touchy Feely and became one of the school’s most popular offerings. The course’s hallmarks are intense introspection, experiential skill-based learning, and the use of coaches to teach students how to create relationships that can make them better managers. In the 2024–25 academic year, 432 students took the course.

1970s

Going Public

Arjay Miller (Photo: Stanford News Service)

Arjay Miller (Photo: Stanford News Service)

When Arjay Miller was offered the deanship of the GSB in 1968, he was president of Ford Motor Company. He had two full-time secretaries and two full-time chauffeurs, and was second in line for the use of 12 private airplanes (after Henry Ford II). But he had also seen the need for effective management and leadership in the public sector and made his acceptance of the deanship conditional on training leaders for it.

Miller had chaired the Economic Development Corporation of Greater Detroit, where he was charged with bringing jobs to the city following urban unrest and deadly riots in 1967. The organization raised $7 million to develop businesses in the city but was, as Miller recalled in a 2008 interview, “a failure.”

“I came to the conclusion, first, businesspeople really didn’t understand the political process or know what to do and how to respond to the new demands being placed on them,” he said in a GSB oral history. “And secondly, the government sure didn’t understand business. The mayor had no plan, no money, nothing. And third, nobody anywhere was doing a great deal about this.” Stanford’s public management program, launched in 1971 and now known as the certificate in public management and social innovation, was the first of its kind.

1980s

Changing the Culture

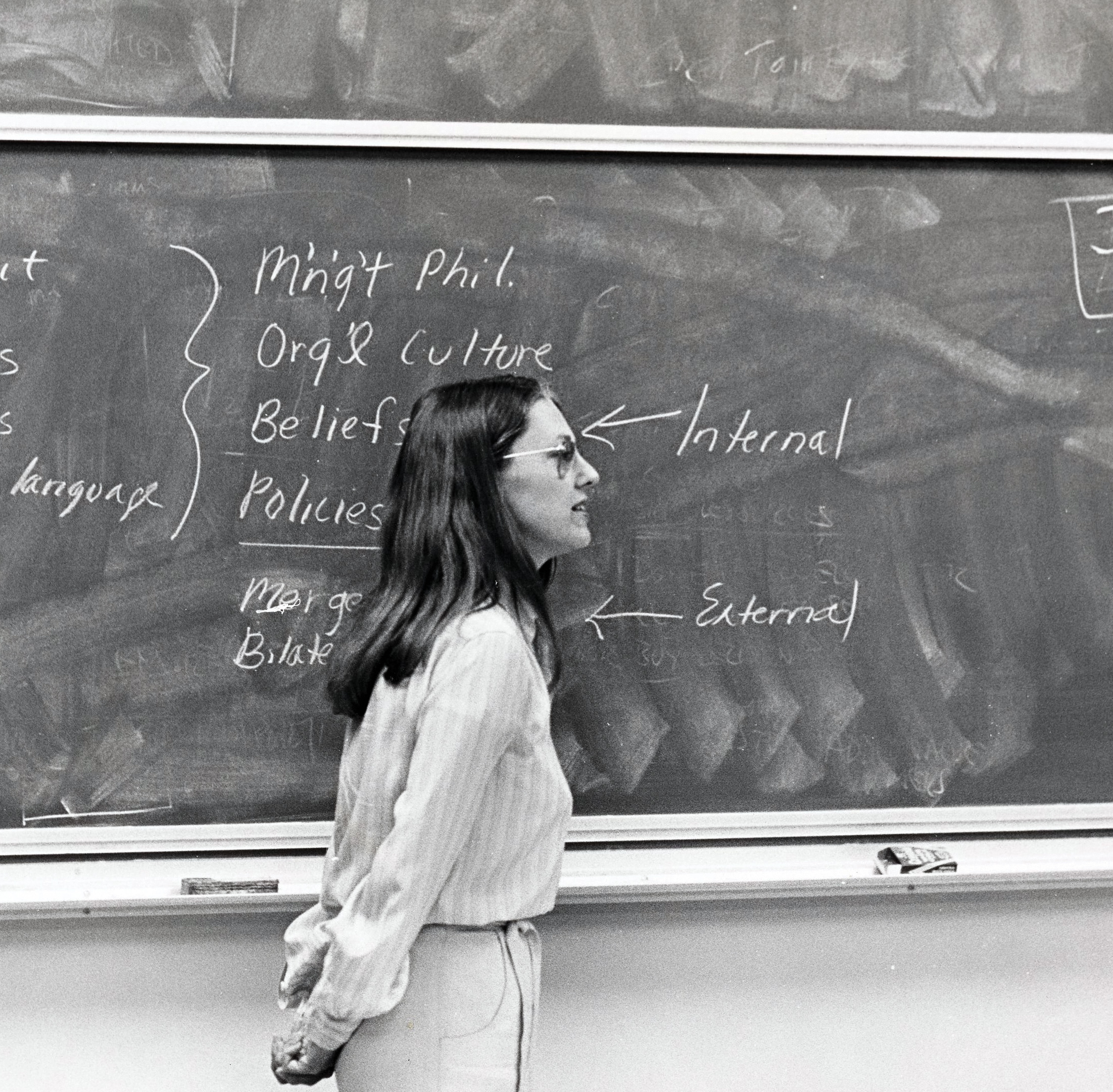

Joanne Martin (Photo: Stanford GSB Archives)

Joanne Martin (Photo: Stanford GSB Archives)

100:1. That was the ratio of men to women on the GSB faculty when Joanne Martin was hired in 1977. Two women had come before her, including influential labor economist Myra Strober, who went on to become a tenured professor at the Graduate School of Education.

“The amount of prejudice against the idea that a woman could be a first-class intellectual was intense,” Martin said in a 2015 oral history. MBA students walked out of her class in protest (only to be sent right back in by Dean Miller), and the two colleagues she admired most told her after she became pregnant that she would never earn tenure. They were wrong. Martin, known for her research on organizational culture, became the first tenured female faculty member at the GSB in 1984. Since 2008, the leading professional association for her field—organizational management—has presented the Joanne Martin Trailblazer Award.

Return on Investment

George Leland Bach, a professor at the GSB and in the department of economics and an expert in the causes and effects of inflation, retired in 1983 after 45 years in academia. As a teacher, textbook author, and task force chair, he influenced the economics education of millions of K–12 and college students nationwide.

Photo: Stanford GSB Archives

Photo: Stanford GSB Archives

In the mid-1980s, GSB students began organizing international trips. Today, all MBA students are required to participate in a global experience program to explore challenging issues facing the world, such as changing social demographics, sustainability, or AI.

1990s

Nobel Wins

William Sharpe (left) and Guido Imbens (Photo: Stanford GSB Archives; Andrew Brodhead/Stanford University)

William Sharpe (left) and Guido Imbens (Photo: Stanford GSB Archives; Andrew Brodhead/Stanford University)

In 1990, professor William Sharpe became the GSB’s first winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, along with two other economists, for work that led to the creation of the Capital Asset Pricing Model, which evaluates the pricing of securities to assess potential investment returns as well as potential risks. Since then, five additional GSB professors have won the prize. The latest, in 2021, was awarded to Guido Imbens, who is also a professor of economics, and his MIT colleague Joshua Angrist for their work to discern causation from real-world situations—such as with questions that can’t practically or ethically be studied with randomized controlled trials. The pair’s methodologies have been used to deliver insights on the implementation of economic and social policies, as well as those in medicine and epidemiology.

A Giant Leap for MBAs

Steve Smith (Photo: NASA)

Steve Smith (Photo: NASA)

Steve Smith, ’81, MS ’82, MBA ’87, is to this day NASA’s only astronaut with an MBA. In 1994, he embarked on his first of four space shuttle missions, which included seven spacewalks. He also served as deputy chief astronaut, the second in command at the U.S. Astronaut Corps.

Good Behavior

In 1997, GSB professor Margaret Neale, an expert in bargaining and negotiation, helped create what became known as the school’s Behavioral Lab, or B-Lab, where GSB faculty and PhD students have run human experiments to explore concepts ranging from happiness and reciprocity to inequality and power.

The Boom

In 1999, professors Haim Mendelson and Garth Saloner, MA ’81, MS ’82, PhD ’82, a future GSB dean, launched the Center for Electronic Business and Commerce. When others were predicting that “electronic firms” would destroy corporations, Mendelson and Saloner saw the future differently. “We didn’t heed the calls to establish electronic business as a separate field of study,” Mendelson said in an interview with the GSB. “Instead, we integrated it with the school’s traditional teaching and research programs.” Two years later, they predicted that electronic business would continue to create value and, over time, transform industries. The center created 54 research papers, seven business courses, and 130 teaching cases that were used worldwide. Over time, the professors’ predictions came true. They shut the center down, as planned at its founding, in 2005.

2000s

Home Sweet Home

Photo: Elena Zhukova/Stanford GSB Archives

Photo: Elena Zhukova/Stanford GSB Archives

After nearly 30 years in the Quad, the school headed up Lasuen Street to a new building, later dubbed GSB South. Littlefield Management Center was added next door in the mid-1980s. In 2008, ground broke on the Knight Management Center, a 360,000-square-foot business school campus. The school relocated there in 2011.

Sticky Stuff

Urban legends about kidney theft; a wildly successful anti-littering campaign slogan (“Don’t Mess with Texas”); Sony’s “pocketable radio.” The research and writing of GSB professor Chip Heath, PhD ’91, revealed six principles that make for successful messages and how those traits can make people better communicators.

2010s

Worldwide Webs

In 2011, the GSB launched the Stanford Institute for Innovation in Developing Economies, or Stanford Seed. Today, it delivers business training and resources to founders and CEOs in 43 countries and, according to surveys, has created nearly 50,000 jobs and added $1.7 billion in revenues to local economies. In 2023, the GSB and the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability launched the Stanford Ecopreneurship program to accelerate work on climate solutions in private, public, and nonprofit entities.

Baba Shiv (Photo: Linda A. Cicero/Stanford News Service)

Baba Shiv (Photo: Linda A. Cicero/Stanford News Service)

In general, you’re far better off making decisions in the morning.

Tech For More

GSB professor Susan Athey, PhD ’95, launched the Golub Capital Social Impact Lab so that students from CS, engineering, education, and economics can work together to help organizations develop digital tools and expertise that are generally unavailable or unaffordable for all but the largest technology companies. The lab has studied how to increase charitable donations; evaluated methods to speed the delivery of health care; and built a tool to help people compare the benefits of government-funded training programs.

Rise of the Entrepreneurs

The Center for Entrepreneurial Studies was created in 1996 as a one-stop shop for students interested in pursuing their own ventures. Today, the GSB offers more than 50 courses on entrepreneurship and innovation—including the popular Startup Garage, launched in 2013 by the GSB and Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design. The course aims to give students hands-on practice designing and field-testing new business concepts that address real-world needs.

‘Ask yourself: “Who is my audience and what is my goal in engaging them?”’

2020s

Power Points

Brian Lowery (Photo: Andrew Brodhead/Stanford University)

Brian Lowery (Photo: Andrew Brodhead/Stanford University)

Professor Jeffrey Pfeffer’s research on power aimed to unveil the forces that shape our workplaces. Pfeffer, PhD ’72, wrote 7 Rules of Power: Surprising—but True—Advice on How to Get Things Done and Advance Your Career to help leaders change organizations.

Professor Brian Lowery, a social psychologist, studies social identities. In his book, Selfless: The Social Creation of “You,” he argues that the “self” as we know it—that “voice in your head”—is created through our relationships and social interactions.

Looking to the Future

Sarah Soule (Photo: Nancy Rothstein)

Sarah Soule (Photo: Nancy Rothstein)

In its 100th year, the GSB appointed Sarah Soule as dean. A member of the school’s faculty since 2008, Soule has focused her research on organizational theory, social movements, and political sociology. As dean, she plans to build on two platforms launched by Levin: the GSB’s business, government, and society initiative, which funds cross-disciplinary thinking and research aimed at solving the world’s most pressing problems; and the school’s investing initiative, which includes a new summer finance course for incoming MBA students interested in investment careers. “I see them both as directly tied to the idea that democracy, capitalism, and the rule of law are important institutions that, when functioning well, lead to great economic prosperity,” says Soule.

Fresh Faces

In 2023, the GSB launched Pathfinder, a pilot program that offers courses in finance, entrepreneurship, and other business topics to college juniors, seniors, and co-

terminal master’s students.

55%

proportion of U.S.-based GSB alums who live on the Pacific Coast. (About 3/4 of alums are U.S.-based.)

Rebecca Beyer is a freelance writer in the Boston area. Email her at stanford.magazine@stanford.edu.