After Jennifer Felix’s father died in 2021, she was so consumed with arrangements that she simply had his belongings trucked, sight unseen, from his home in Arizona. Last winter, Felix, who owns several canine daycares near her home on Long Island, decided it was time to finally address his stuff. On January 23, while she went to work, her husband, Nelson, emptied out the storage unit. That night, a wooden crate awaited her in the kitchen. “I’m pretty sure it’s a typewriter,” Nelson told her. “It’s heavy.” But when Felix looked inside, it was unlike anything she’d ever seen. “I’m like, ‘This isn’t just a typewriter. These are not English symbols.’ ”

Her husband posted photos to a Facebook page he found called “What’s My Typewriter Worth?” before they sat down for dinner. By the time they were finished, messages had poured in from people around the world: It was a singular prototype known as the MingKwai—the first Chinese typewriter to have a keyboard. Some were offering to buy it; others were beseeching them to make sure it ended up in the right hands. (There were varying opinions about whether that meant in China, Taiwan, or the United States.) As the couple went to bed, messages continued with an urgency that made them wonder if it had been smart to announce the machine was in their home. “We just kind of laid down and we were like, ‘What the hell is happening right now? What did we just stumble on?’ ” Felix says.

MACHINE LEARNING: Mullaney hopes to create a working replica of the MingKwai for research purposes. (Photo: Didi von Boch)

MACHINE LEARNING: Mullaney hopes to create a working replica of the MingKwai for research purposes. (Photo: Didi von Boch)

Many commenters were tagging Thomas Mullaney, a Stanford history professor who’d literally written the book on the MingKwai, in which he had lamented the machine was now likely entombed in a landfill if it hadn’t been scrapped for parts. Years earlier, Mullaney had been digging in the archives of the National Museum of Natural History when he found the only known photograph of the MingKwai with its internal gears revealed. “It was like finding a picture of Great-Great Grandpa,” he says. “I’m not going to see Great-Great Grandpa, but I found a picture of him.” Now looking on Facebook, Mullaney was stunned to see the forebear not only in one piece, but in near-pristine condition. His elation quickly turned to dread. The machine could so simply disappear again. Mullaney dashed off a plea to not sell it on the Facebook thread, then started searching Whitepages and LinkedIn for Nelson’s name. Eventually the Felixes replied to him—they would call in the morning. “There was a good two hours of panic,” Mullaney says.

And that—with the assistance of a private donation—is the short version of how a 78-year-old typewriter unlike any other came to be sitting on a medical CT scanner in the Stanford radiology department in October as a team of scholars awaited a view of its inner secrets. The goal is to build a working replica. “Because this is a one-of-a-kind artifact, we cannot operate it for fear of damaging it, and disassembly is obviously impossible,” Mullaney says. “The only viable way to investigate its internal workings is through nondestructive imaging—to see what lies under the cover.”

The Invention

The 26 letters of English readily fit on a keyboard so compact we hardly stretch our hands to reach our P’s and Q’s. But the tens of thousands of Chinese characters? In popular imagination, you’d sooner get an elephant through a keyhole than fit them on anything like a standard keyboard, Mullaney says. There’s ample allusion to the absurdity of even trying throughout 20th-century Western culture, from 1900s newspaper cartoons that depicted Chinese typewriters the size of houses to the 1990 video for the hit song “U Can’t Touch This” that featured rapper MC Hammer doing a frenetic sidestep that came to be dubbed the “Chinese Typewriter.” It was reference, Mullaney says, to the furious back-and-forth operating such a giant machine must surely demand.

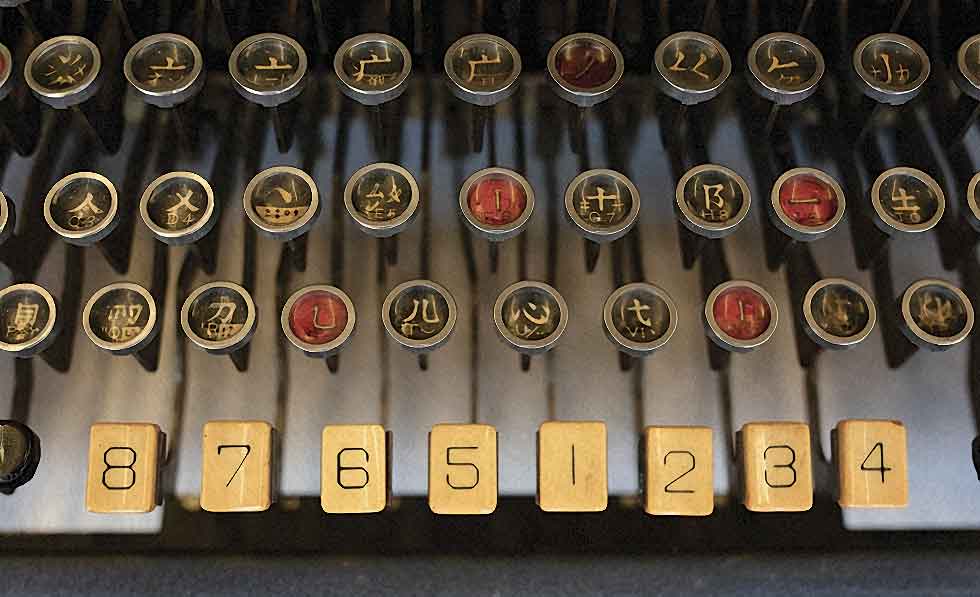

The MingKwai—roughly “clear and fast” in Mandarin—was proof of a far more elegant possibility. Produced in 1947, it had only 72 keys—fewer than a MacBook today—but by pressing them in combinations related to the shapes in the desired character, the user could summon as many as eight options into view in a small window called the “magic eye.” The typist then chose among them. The result was a desktop device that could produce tens of thousands of options, enough for every Chinese character in existence. It was a marvel—and a missed opportunity. For a variety of reasons, not least the business uncertainties created by the ongoing Chinese Communist Revolution, the MingKwai was never produced beyond a single prototype. After decades of trying to realize his vision, the typewriter’s inventor—the Chinese author, linguist, and polymath Lin Yutang—was too financially and emotionally drained to continue. But while the MingKwai simply disappeared, its significance endured. “It is the great-great-whatever parent of the entire Chinese digital age, at least in terms of human-computer interaction,” Mullaney says.

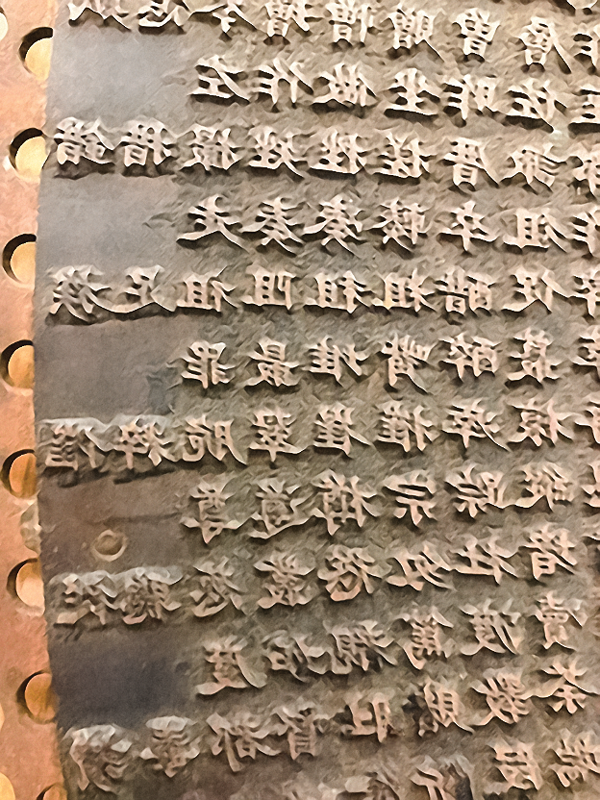

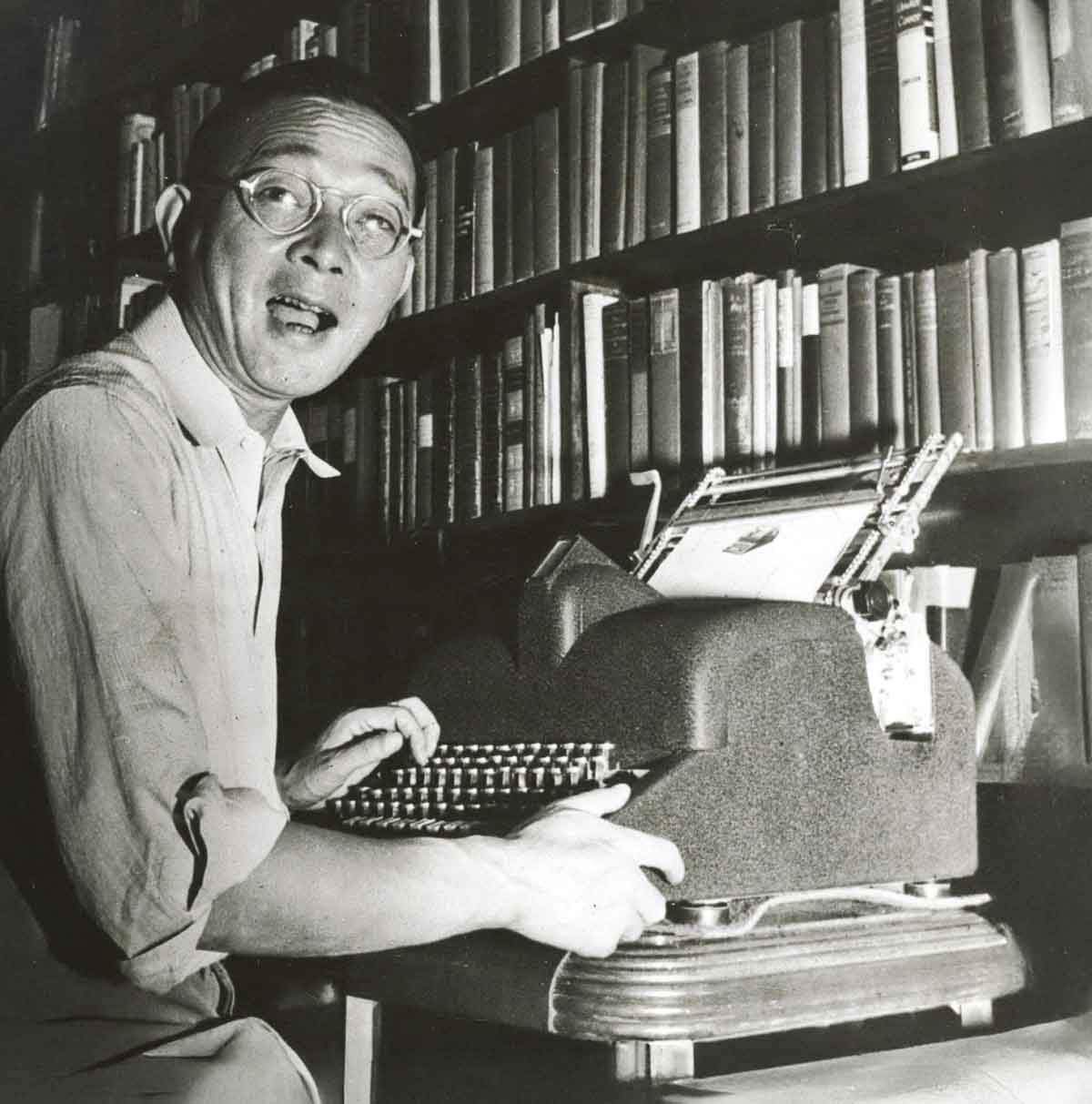

COMBO LOCK: By pressing the keys in particular combinations, a typist could summon as many as eight options into view in a small window called the “magic eye,” as designed by inventor Lin Yutang, above. (Photos, from top: Didi von Boch (2); Keystone Press/Alamy Stock Photo)

COMBO LOCK: By pressing the keys in particular combinations, a typist could summon as many as eight options into view in a small window called the “magic eye,” as designed by inventor Lin Yutang, above. (Photos, from top: Didi von Boch (2); Keystone Press/Alamy Stock Photo)

The Scholar

Having first studied Mandarin as a college freshman in the mid-’90s, Mullaney never really knew a world when Chinese could not easily be written on a computer-based word processor. He’d never seen a mechanical Chinese typewriter, and never really contemplated one. Even MC Hammer’s exertions in parachute pants had passed him by. But in 2007, Mullaney was browsing a bookstore in Beijing when he came across something that would send him deep into the subject: a dictionary of “ambiguous” Chinese characters that had fallen into such disuse that nobody knew how to pronounce them or what they meant.

The book cast Mullaney’s mind on a search for explanations, and he began to think about the funneling effect of technology on a language with no alphabet and tens of thousands of characters. With ink and brush, all writing was equally within reach. But in the industrial age, where, say, a printing press could only create a character from a physical plate, new means of communication provoked an implicit question—which characters should make the cut? Mullaney was in his Stanford office one day when he started to wonder about what role the typewriter might have played in this winnowing, and he realized he had no clue what a Chinese typewriter even looked like. Two hours later, he had reams of patent information from dozens of engineers and inventors from the early 20th century and an intense new focus.

Mullaney has an eye for a story hiding in plain sight and a fascination with what he calls “world-making,” the process by which societies shape reality. His first book, Coming to Terms with the Nation, won raves for its examination of China’s 1954 Ethnic Classification project, a sweeping government effort that funneled hundreds of different ethnic groups into the 56 categories that still stand today. “We all know that China has 56 official ethnic groups, but until now none of us knew precisely why,” one reviewer wrote. In the Chinese typewriter, Mullaney saw an inverse story: an outlier resisting absorption into the supposed universal model, the Western-style typewriter and its partner, a Western alphabet. (Mullaney starts this month as director of the program in science, technology, and society, a nod to his interdisciplinary scholarship.)

Mullaney would throw himself into the typewriter research, a process that would take him to archives around the world and crowd his apartment with what was probably the world’s largest collection of Chinese typewriters, manuals, and related paraphernalia. (It has since been donated to Stanford.) It would lead him to write an award-winning book, The Chinese Typewriter. And ultimately it would bring him, and Stanford, what he calls “perhaps the most well-known, but also most poorly understood, Chinese typewriter in history.”

The American Typewriter

Mullaney’s tale of the Chinese typewriter begins with its American cousin. The first mass-produced typewriters began to circulate in the United States soon after the Civil War and were produced by Remington, an arms maker whose rifles had been synonymous with the conflict. The Remington 1, the first typewriter with a QWERTY keyboard, was overshadowed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition by Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, but an updated model—now with a “shift” key—exploded in popularity. Remington was soon on a global march with branches throughout Europe and representatives all over the Americas, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

With minor adjustments, its typewriters—and those of rivals—were able to accommodate the accents of French, the right-to-left progression of Hebrew, and the ligatures of Arabic. But, if need be, language would be made to submit to machine. The American inventor of the first Siamese typewriter could find no way to fit the full Thai script on a typewriter created for English, Mullaney writes. So, the designer jettisoned two consonants, dooming them to lasting oblivion. Chinese, however, defied such limited surgery. And while some—in China and elsewhere—argued for radical change to make the writing system compatible with modernity, the proposal met strong resistance. “We Chinese wish to say that the privilege of a mere typewriter is not tempting enough to make us throw into waste our 4,000 years of superb classics, literature, and history,” a 1913 editorial in Chinese Students’ Monthly declared. (While spoken Chinese languages can be “quite distinct from one another,” Mullaney says, the conversation regarding typewriters is “always about Chinese’s standard written form.”)

STUDY HALL: MingKwai research collaborators Adam Wang, MS ’08, PhD ’12, Zhaohui Xue, Regan Murphy Kao, Robert Bennett, Mullaney, and Bryant Lin apply modern tools to an historical inquiry. (Photo: Timothy Archibald)

STUDY HALL: MingKwai research collaborators Adam Wang, MS ’08, PhD ’12, Zhaohui Xue, Regan Murphy Kao, Robert Bennett, Mullaney, and Bryant Lin apply modern tools to an historical inquiry. (Photo: Timothy Archibald)

Stymied in their attempts to make a product, Western typewriter manufacturers ultimately acted as if the Chinese market didn’t exist. In 1958, the Italian typewriter giant Olivetti bragged that its machines “write in all languages,” a boast that conveniently forgot the world’s then-most populous country. “They knew full well that Chinese was not included,” Mullaney says. “But they had set the terms of what counts as universal.”

The Chinese Typewriter

By contrast, the Chinese typewriter developed outside what Mullaney calls the “Remington monoculture.” The first functional Chinese typewriter—a prototype created in 1897 by an American missionary named Devello Sheffield—could hardly have looked less like its Western kin. Eager to write without relying on Chinese secretaries, Sheffield consulted with typesetters near Beijing before commissioning a device that resembled a round table. Its surface contained 4,662 characters grouped in three regions—“very common,” “common,” and “less common”—that could be rotated over a manuscript.

Like the MingKwai, the invention would never be mass produced, but it exemplified challenges ahead. As a missionary, Sheffield had obvious reason to want to efficiently write Jesus—Yesu in translation. But the character for su was otherwise of minor importance. So where to put it? “Sheffield was decisively indecisive,” Mullaney writes. “He included two copies of su on his machine, placing one where it belonged empirically—within the list of 2,550 ‘less common characters’—and the other where it belonged theologically—within the exclusive list of ‘very common characters.’ ” With finite space, such double-booking meant less real estate for other characters. It was a problem that nagged at all attempts to shrink the lexicon for the sake of a machine. Choices would eventually become unresolvedly personal.

Other strategies included typewriters that tried to replicate brush strokes or create characters from radicals, the semantic building blocks that repeat in characters. These approaches would founder on their own challenges. The version of the Chinese typewriter that would come to predominate through the 20th century—developed by inventor Shu Zhendong following the work of Zhou Houkun—was not unlike Sheffield’s device. Its design principle was premised on amassing the most common characters. But in this rendition, the characters were contained on thousands of moveable slugs on a flat bed. With tweezers, characters could be added and removed. You could have your su where—and if—you liked.

By gliding a selection lever over the bed, a trained user could type 2,000 characters an hour, but the typewriters never had the ubiquity of their Western kin. They were large, hard to transport, and customizable to a degree that could render them unusable except by the person who had arranged the slugs. A newcomer would be simply lost in the layout.

Zhaohui Xue, the Chinese studies librarian at Stanford’s East Asia Library, remembers working at a government agency in China in 1980 when such typewriters were still the norm. “In the power hierarchy, as I observed it, the real power was not the director or the leaders, it was the typist,” she says. “She could slow-roll your work. You really had to stay on her good side.” When the MingKwai arrived at Stanford, Xue says she was most astonished by its size. The Chinese typewriters of her memory would fill half a desk. The MingKwai—for all it contained, in terms of characters and history—was not much larger than a Western typewriter. “It was truly stunning to me.”

The MingKwai

Indeed, judged by its exterior, the MingKwai looked like the device that had finally brought Chinese into the United Nations of QWERTY-ish typewriters. But its cover hid an interior unlike anything else—a tight cluster of 36 octagonal bars each lined with hundreds of characters and packed, Mullaney observed, like “Ferris wheels inside Ferris wheels inside Ferris wheels” that rotated and revolved like moons and planets in a solar system. “Lin’s system encompassed a total of forty-three separate axes of rotation: thirty-six metal bars rotating around their own lunar axes, six higher-order cylinders rotating around their own planetary axes, and finally one highest-order cylinder rotating around a singular, stellar axis,” Mullaney writes.

MID-CENTURY MODERN: The MingKwai’s inventor uncovered “an entirely different way of understanding human-machine interaction,” Mullaney says. (Photo: Didi von Boch)

MID-CENTURY MODERN: The MingKwai’s inventor uncovered “an entirely different way of understanding human-machine interaction,” Mullaney says. (Photo: Didi von Boch)

At the time of its creation, virtually every other typewriter in existence exemplified a “what-you-type-is-what-you-get” approach, Mullaney says. You pushed a key, and the corresponding letter hit the page. But when you pressed a key on the MingKwai, nothing appeared. Nor did it when you pressed a second key. Instead, there was a turning of bars and gears. Only when the typist chose from the options displayed in the “magic eye” would ink hit paper. The MingKwai didn’t type letters; it retrieved them. Its keys weren’t commands; they were notes to be combined into tens of thousands of chords. Lin had set out to make a better Chinese typewriter. He had uncovered, Mullaney says, “an entirely different way of understanding human-machine interaction.”

Even nearly 80 years later, the mechanics of the metallic algorithm that enable this are staggering, Mullaney says. He’s adamant about not removing anything beyond the machine’s detachable cover. “Nothing else can be disassembled because we have no way, we have no knowledge of how to put it back together.” Instead, a team of experts from the School of Engineering, the School of Medicine, and outside museums are making casts, scans, and measurements of the machine in hopes of reconstructing the device in duplicate. “Since the original cannot be used, the only way to understand its mechanism in practice is to construct a faithful, working replica,” he says.

If the researchers succeed, the copy will be only the second MingKwai to exist, a reminder that for all the typewriter’s glory, it was a commercial dud. The MingKwai publicly debuted to rave reviews. An August 1947 New York Times article, which quotes a manager of the Bank of China in New York, is characteristic of press accounts across the United States: “I was not prepared for anything so compact and at the same time comprehensive, so easy of operation and yet so adequate,” the bank manager said. But in the boardroom, momentum flagged. When Lin and his daughter demonstrated the machine to a group of Remington executives in New York, the machine stalled, and historical headwinds would prove only harsher. Businesses were concerned that China’s ascendant Communists would not honor patents, and there were fears that Mao Zedong would romanize the writing system, Mullaney says. Then came the death knell, the Korean War, which put the United States and China on opposite sides of armed conflict. By that time, bankrupt and exhausted, Lin had sold the prototype and the commercial rights to the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, a printing company in Brooklyn, where—Mullaney would discover—Felix’s grandfather was a machinist.

Felix remembers him as a brilliant man building steam-engine trains in his basement—she doesn’t know if he worked on the MingKwai. He clearly esteemed the machine. It was kept in meticulous condition for decades in a handmade crate. Her dad too must have known he had inherited something special. Why else, Felix says, would he have hauled such a 50-pound weight to Arizona from New York? She downplays her own importance in the saga. “I’m just a girl from Long Island who found a frickin’ typewriter.” But she’s happy it has landed at Stanford. “I wanted it to go somewhere where they would appreciate it,” she says. “I think it was important for it to be there.”

Lin died in 1976 thinking he failed at the MingKwai, Mullaney says. But his prophetic reimagining of a keyboard’s potential would in time change the world. The MIT engineers who created the first Chinese-language computer in the 1950s leaned on Lin’s input research to enable Chinese typing using a QWERTY keyboard. And Mullaney traces a direct line of descent from there to modern China’s multi-trillion-dollar IT market. Not long ago, the very idea of a Chinese typewriter was held up as either a joke or an impossibility. Today, the fastest Chinese typists can sit at the same keyboard the rest of the world uses and easily outpace their English-language equivalents thanks to combinations of keystrokes that descend from the MingKwai. Clear and fast—and prescient.

|

|

|

Last summer, after learning their local library was planning an exhibit of historic typewriters, David and Elise Adams offered a contribution: a large metal disc covered in thousands of precisely rendered Chinese characters. The two knew little about it other than what David had deduced decades earlier: It was part of an old Chinese typewriter. David had chanced upon the disc while working for mainframe manufacturer Univac in Pennsylvania in the early ’80s. One day, a tractor-trailer stopped in the parking lot with a load of typewriters from around the globe for sale. Univac was part of a conglomerate that included typewriting pioneer Remington, and the corporation was evidently shedding collections tied to this heritage. “It just seemed so curious and nothing like anything I had ever seen in my life,” David says. He offered $17—all the cash in his wallet—and rolled the disc to his car. Since retiring to Castine, Maine, in 2001, the couple had kept the beloved collectible in a workshop amidst “tools, car parts, lawnmowers, scrap lumber, and poetry magazines,” son Christiaan Adams recalls. At the library exhibit, the disc stopped visitors in their tracks, says Kathryn Dillon, library technician at the Witherle Memorial Library. “It’s just so beautiful and so unusual,” she says. It weighed around 30 pounds and spanned about 30 inches, yet glided perfectly on a pivot, at least until the library’s youngest patrons got hands on it. “It almost spun off the table a couple times,” Dillon says. The only frustration for Dillon was her inability to add much context to the display. The Adamses had uncovered that it was likely part of the first Chinese typewriter, a prototype created by Devello Sheffield,a Civil War veteran turned missionary to China. Dillon assumed several such devices must have made their way into the world, but she was confounded by how little else she could glean. Finally, she sent photos of the disc to the professor whose writings on the Sheffield had guided her—Stanford historian Tom Mullaney. “I knew there was something not right—something not complete,” she says. “Someone needed to figure it out. And that someone was most likely going to be Tom.” She’d barely hit send when her phone rang. It was Mullaney. The one and only Sheffield had disappeared from the public eye more than a century earlier. After seeing more photos, Mullaney was confident it had been found. It was another stunning moment for Mullaney, who was still high on the reappearance of the MingKwai. Now the key part of the first Chinese typewriter had been rediscovered. “This was the first attempt to mechanize Chinese,” Mullaney says, “the first ever attempt to merge the mechanical age and Chinese writing.” It was almost too much, he says. The device was quietly withdrawn from the reach of 5-year-olds. “I went to the bank and said, ‘Do you have space for a big disc?’ says Elise Adams. “And they said, ‘No, no, no, we have only space for money and jewelry, but not 30-inch discs.’ So, we took it home.”

Mullaney approached Stanford Libraries about acquiring the Sheffield as it had the MingKwai. “Immediately we’re like, ‘Yes, we want it,’ ” says Regan Murphy Kao, director of Stanford’s East Asia Library. The library hopes to develop an East Asia Media Lab where the Sheffield, the MingKwai, and related items are on display. In November, the Adams family agreed to donate the device to Stanford. “We were always in awe of this thing, seeing this round, heavy brass thing with these beautiful signs,” Elise says. “It was amazing that we finally found something out about it.” Photos: Witherle Memorial Library (2) |

Sam Scott is a senior writer at Stanford. Email him at sscott3@stanford.edu.