Nick Thach is a big fan of theme parks. So when, after his junior year, he got an internship with NBCUniversal testing roller coasters and crunching data for its new park, Epic Universe, he jumped at the chance.

There was one hitch: The internship was for the academic year. He would need to stop out.

“I really wanted to ride roller coasters and have some fun,” the management science and engineering major says. “And I felt like I wasn’t ready to graduate.” Thach, ’25, took a leave of absence (known better to some generations as stopping out) to go live his dream.

“It was the type of work experience I’d hoped for,” he says. “And it was the break from school I needed.” But when he returned this fall for his delayed senior year, it was to a different Stanford—one that no longer included most of his Class of ’25 friends. “Returning has been tough,” he says. “All my friends are gone. I sort of had to start from scratch.” But there was also an upside: “Taking time off made me appreciate school more,” he says.

Thousands of Stanford undergrads have taken time off over the years for all kinds of reasons—from starting a family to launching a business and from volunteering in refugee camps to going pro. What’s unusual is how easy Stanford makes it to come back, whether it’s been one year or 65. “We have students who want to pursue opportunities,” says Christine Lee, director of academic support programs for Stanford’s Office of Academic Advising. “Students have family emergencies or leave for missionary work. Stanford saves a place for you to return.”

Stopping out can induce emotions that range from excitement about a new opportunity to embarrassment about leaving due to tremendous stress. “Sometimes, students are looking for reassurance,” says Lee. “They may almost want someone to tell them it’s OK.”

It’s OK.

Here’s how things turned out for six stop-outs.

Jessica Fry, ’19

Stopped out: 2 years

Why: Broadway called

Today: Doctoral candidate in physics at MIT

Toward the end of her sophomore year, Jessica Fry got a call from her agent saying, “Hey, can you get to New York on Tuesday? There’s a role on Broadway I think you’d be great for.”

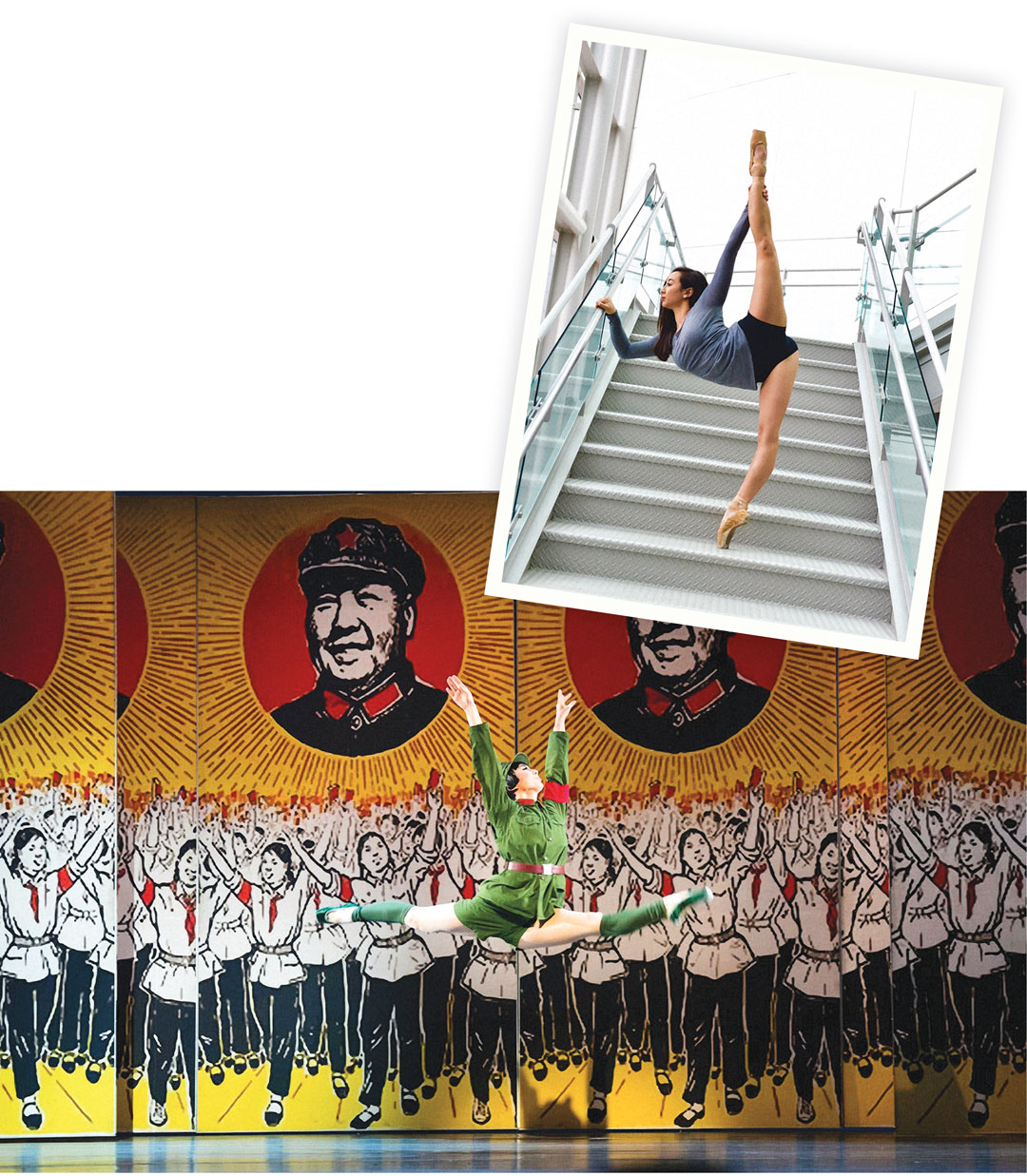

Fry had danced since she was 3, and she won Miss Dance of America in 2015. That landed her an agent. But dance was never her only love. “I am passionate about both performance arts and particle physics, which is why I went to Stanford, where I could do both right off the bat,” she says. She was a member of Cardinal Ballet as well as Stanford’s Alliance hip hop and Urban Styles jazz dance teams when she landed the Broadway gig.

She and her parents discussed both the opportunity of performing on Broadway—very possibly a once-in-a-lifetime shot—and her concerns about leaving school without knowing if or when she would return. It helped to know that Stanford would leave the light on. Ultimately, she says, “when Broadway comes calling, you don’t say no.”

In October 2017, Fry made her Broadway debut as part of the ensemble in M. Butterfly. When

the play’s run ended in December of that year, she stayed on in New York, appearing in an episode of The Americans, then touring for a year as an ensemble member and understudy for Veruca Salt in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. At the end of the tour, she found herself at a crossroads: forge ahead as a performer or return to Stanford to pursue particle physics?

“A part of me thought that Broadway would be the entirety of my career,” Fry says. “But I got a little bit sad, because that would have been turning off a whole other passion I have for physics and for the sciences. I feel like I need to have both in my life to be a happy person.”

AMONG THE STARS: Fry left the footlights to study dark matter. (Photos, from top: Courtesy Jessica Fry (2); Sara Krulwich/The New York Times/Redux)

AMONG THE STARS: Fry left the footlights to study dark matter. (Photos, from top: Courtesy Jessica Fry (2); Sara Krulwich/The New York Times/Redux)

Vince Gotera, ’75

Stopped out: 6 Years

Why: To have more control over his Vietnam War military service

Today: Professor emeritus of English at the University of Northern Iowa; poet laureate of Iowa

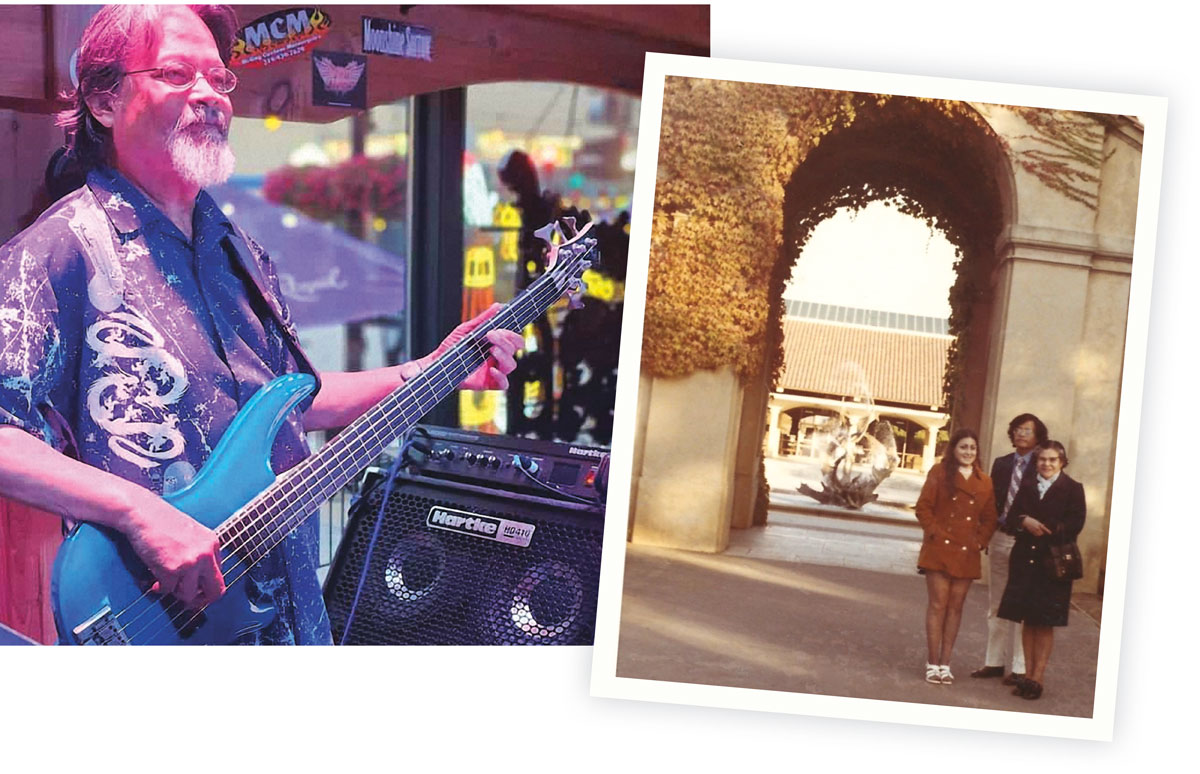

Two things happened just as Vince Gotera was entering Stanford in 1971: The Selective Service System lottery assigned him the number 30, and the military draft exemption for students was phased out. After two quarters on campus—newly married, seeking a job, and sure he would be drafted—he took matters into his own hands. “I enlisted in the Army in order to have some control over what I would be doing,” he says.

Gotera served as a military pay clerk and was able to remain in the United States for his three years of service. Afterward, he returned to school but couldn’t afford Stanford, so he attended City College of San Francisco and then San Francisco State. For his final year, his father offered to pay for his return to the Farm.

“Probably my dad thought the prestige of a Stanford degree would be good for me and my career—which it has been,” Gotera says. He returned to Stanford a father himself, commuting from Daly City and squeezing four quarters’ worth of courses into three. “It was a pretty intense year,” Gotera says.

After graduation, he taught high school English but soon discovered he wanted to teach college students. He earned an MFA and a PhD and did just that for more than 40 years, landing at the University of Northern Iowa in 1995. Among his books of poetry are Fighting Kite, about his dad, and Ghost Wars, about the effects of war, which won the 2004 Global Filipino Literary Award in Poetry. He also won a creative writing fellowship in poetry from the National Endowment of the Arts in 1993, served for 16 years as editor of the North American Review, and for three years edited Star*Line, a long-running publication of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association (apt preparation for his latest book of poetry, Dragons & Rayguns). In his two-year term as poet laureate of Iowa, Gotera told the Northern Iowan, “I would like to dispel the stereotype that many people have about poetry that it’s hard to understand and it’s too damn serious.”

Gotera credits Stanford with giving him the skills and the courage he needed to pursue graduate education. His English professors on the Farm encouraged his love of writing, he says. For years, he kept in touch with Belle Randall, MA ’73, a Stegner fellow who’d taught the first poetry course Gotera took, in his first year. “One of the things I loved about Stanford was that students were treated as family,” Gotera says. “Stanford was the most student-friendly university I’ve ever gone to. I’ve been to a lot.”

WORDS THAT SING: As poet laureate, Gotera travels throughout Iowa for readings and workshops. As a bassist, he plays in the blues-rock band Deja Blue. [Photos, clockwise from top: Sean O’Neal; Courtesy Vince Gotera (2)]

WORDS THAT SING: As poet laureate, Gotera travels throughout Iowa for readings and workshops. As a bassist, he plays in the blues-rock band Deja Blue. [Photos, clockwise from top: Sean O’Neal; Courtesy Vince Gotera (2)]

Thomas Isakovich, ’99

Stopped out: 7 years

Why: To run TrueSAN Networks

Today: Founder and CEO of Nimbus Data

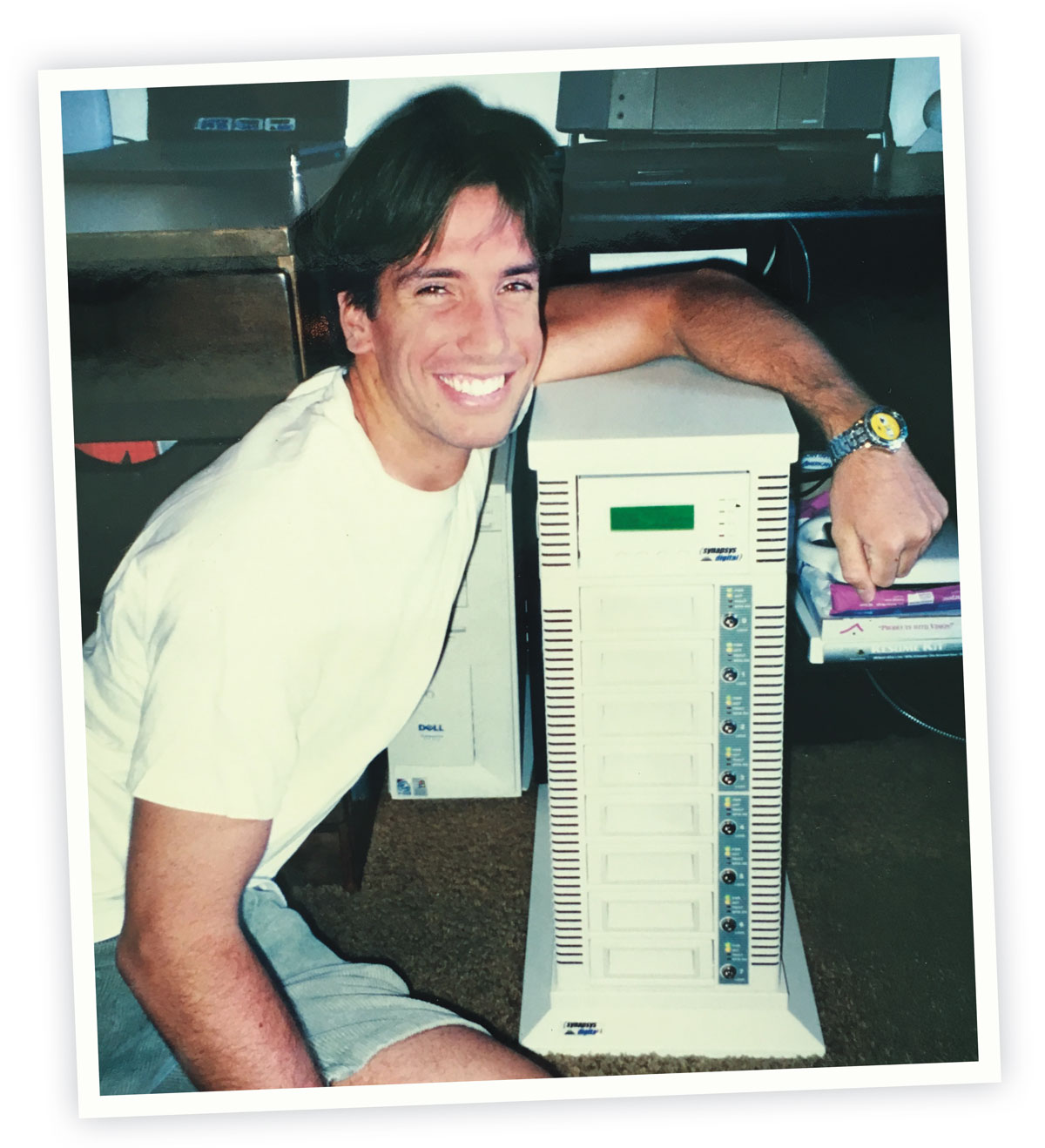

During Thomas Isakovich’s first two years at Stanford, he spent early mornings at rowing practice and late nights launching a data storage start-up from his rooms in Larkin and the Theta Delta Chi house.

“It got to the point where I just didn’t have time to go to class,” he says. When his adviser pointed out his low grades and said he would need to choose between his business and school, Isakovich stopped out. His adviser understood. His dad, on the other hand, did not. He said that if Isakovich left school, he’d have to pay his own way when he returned.

“I said, ‘OK, well, the business is profitable,’” Isakovich says. “‘I’ll keep my expenses low, and I’ll figure it out.’ I had no idea what I was in for.” Thus began a six-year odyssey as an entrepreneur, raising $27 million from investors and later navigating the demise of TrueSAN when the dot-com bubble burst. Isakovich was 26.

“I decided I was going to start another company and keep it lean and mean this time,” he says. That company became Nimbus Data, which he has run for 22 years. But his experience out in the business world also made him want to get back to school.

“Frankly, the day-to-day running of a business, there’s a part of your brain that sort of slowly dies,” he says. “I wanted to go back and exercise it again.” Isakovich returned to Stanford full time in 2004, and after hearing a 2005 guest lecture by Condoleezza Rice, then on leave from Stanford to serve as secretary of state, chose to major in political science. He completed an honors thesis before graduating in 2006. “I was so proud of [it],” he says. “It completely gave a rebirth to that intellectual side of me that had been dormant for years. To turn it around and become a top student, that meant a lot. It’s one of the things I’m most proud of in my life.”

DIAL-UP: Isakovich built data storage arrays in his room during his first stint on campus. “Imagine—that giant system was probably 1/4 of the storage you have on your iPhone today,” he says. [Photos: Courtesy Thomas Isakovich (2)]

DIAL-UP: Isakovich built data storage arrays in his room during his first stint on campus. “Imagine—that giant system was probably 1/4 of the storage you have on your iPhone today,” he says. [Photos: Courtesy Thomas Isakovich (2)]

Arthur Alvarez, ’03

Stopped out: 10 years

Why: For his mental health

Today: Associate director of quality enhancement plan at Clemson University

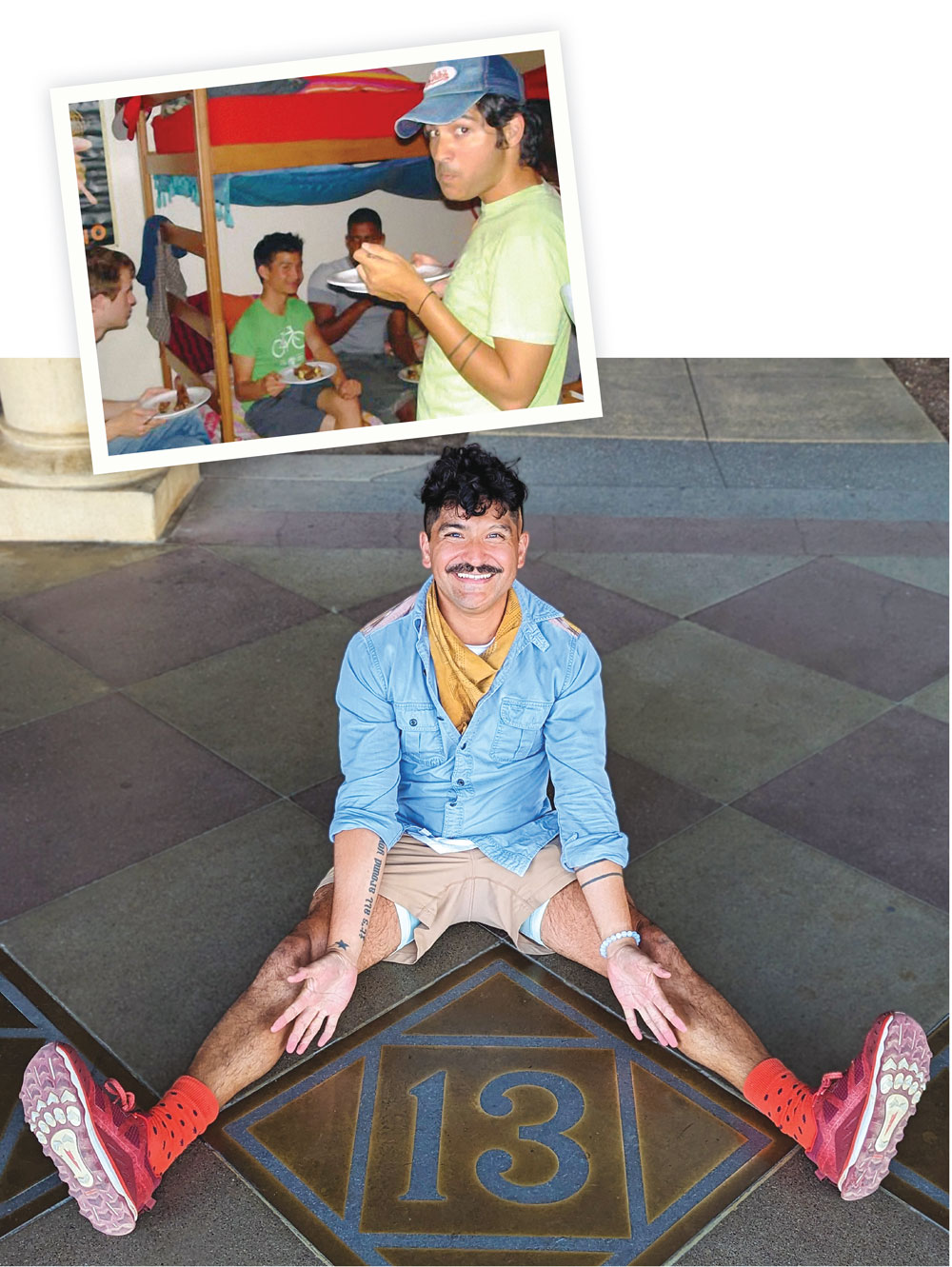

During high school in Fresno, Calif., Arthur Alvarez had a counselor who told him he had the potential to go to Stanford. So he made the Farm his goal. Once that dream came true, and he arrived on campus as a first-generation student, he realized he had no idea how to fit in.

“I freaked out,” he says. “You have some of the top talent across the world there. I just immediately caved under all of it.” There were complicating factors, Alvarez says. His hearing aids weren’t working well, making it hard to follow along in class, and he’d had some anxiety issues in the past. College pressures brought them to a new level.

“I felt this intense amount of shame that made me afraid to leave my dorm room,” he says. “Toward the end of October, I wasn’t even going to classes anymore. I was just sleeping under my bed because I was just so scared to step outside of that door and go into a classroom.”

Over the years, Alvarez took several mid-quarter medical withdrawals along with four leaves of absence. Many times, he thought of giving up, but says his Stanford advisers provided the encouragement he needed to make it to graduation. They also inspired his career choices. After graduation, he earned a master’s in educational leadership at San Diego State and worked as a student adviser for three years at UC San Diego. Now at Clemson, he works with faculty, staff, and students to support experiential learning. “It is wonderful,” he says. “This was the first time that I felt like I was able to utilize a lot of my knowledge.”

His experience at Stanford made him want to help others beginning their higher education journey. “I got to see so many layers of the university as a result of various needs of my own, as well as resources that the university provided,” he says. “Maybe I could help alleviate some of the stress I went through.”

CORNERSTONE: Alvarez (top, right) became what he calls a “professional undergraduate.” Today, that experience informs his career. [Photos, from top: Weronika Hipp: Courtesy Arthur Alvarez (2)]

CORNERSTONE: Alvarez (top, right) became what he calls a “professional undergraduate.” Today, that experience informs his career. [Photos, from top: Weronika Hipp: Courtesy Arthur Alvarez (2)]

Georgiary Bledsoe, ’80, MA ’96

Stopped out: 14 years

Why: Marriage and kids

Today: Semiretired music instructor at Louisburg College

Georgiary Bledsoe stopped out after her sophomore year to get married—she’d fallen for a graduating senior. They moved to New York, where her husband worked for two years on Wall Street. Then they returned to Stanford, where he got his MBA and Bledsoe planned to finish her undergraduate work. But life intervened.

“I had one child by then and was eight months pregnant, so I put off going back,” she says. “After I had four kids, I thought, I’ll never finish now. My brain has turned to mush. I really gave up.” Bledsoe worked as a stay-at-home mom for nearly a decade before taking a job as a substitute teacher in a San Jose school. She taught music and theater classes—and she loved it. When the headmaster encouraged her to get a degree so the school could hire her permanently, she decided it was time to return to Stanford.

She graduated in 1994. But she didn’t go to work at the high school. Encouraged by her adviser, she went to graduate school, earning a master’s in music at Stanford, then a PhD in musicology at Duke in 2002, the same year her youngest child graduated from high school. Since then, she’s done postdoctoral work at Brandeis, taught at Duke, Tufts, and the University of North Carolina, and started Afrocentric music programs for youth across the country.

Looking back on her initial years on the Farm, Bledsoe says, “I was not prepared to really take advantage of the opportunity.” Her goals changed as she matured, she says. “When I look back on it now, I am glad I did what I did. And I’m so glad Stanford made available the opportunity to come back. I wouldn’t change anything.”

IN THE WINGS: Bledsoe acted in plays at Stanford in the ’70s—including in The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (left)—but would wait more than a decade for her academic encore. (Photos, from top: Makalya Williams; Courtesy Georgiary Bledsoe)

IN THE WINGS: Bledsoe acted in plays at Stanford in the ’70s—including in The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (left)—but would wait more than a decade for her academic encore. (Photos, from top: Makalya Williams; Courtesy Georgiary Bledsoe)

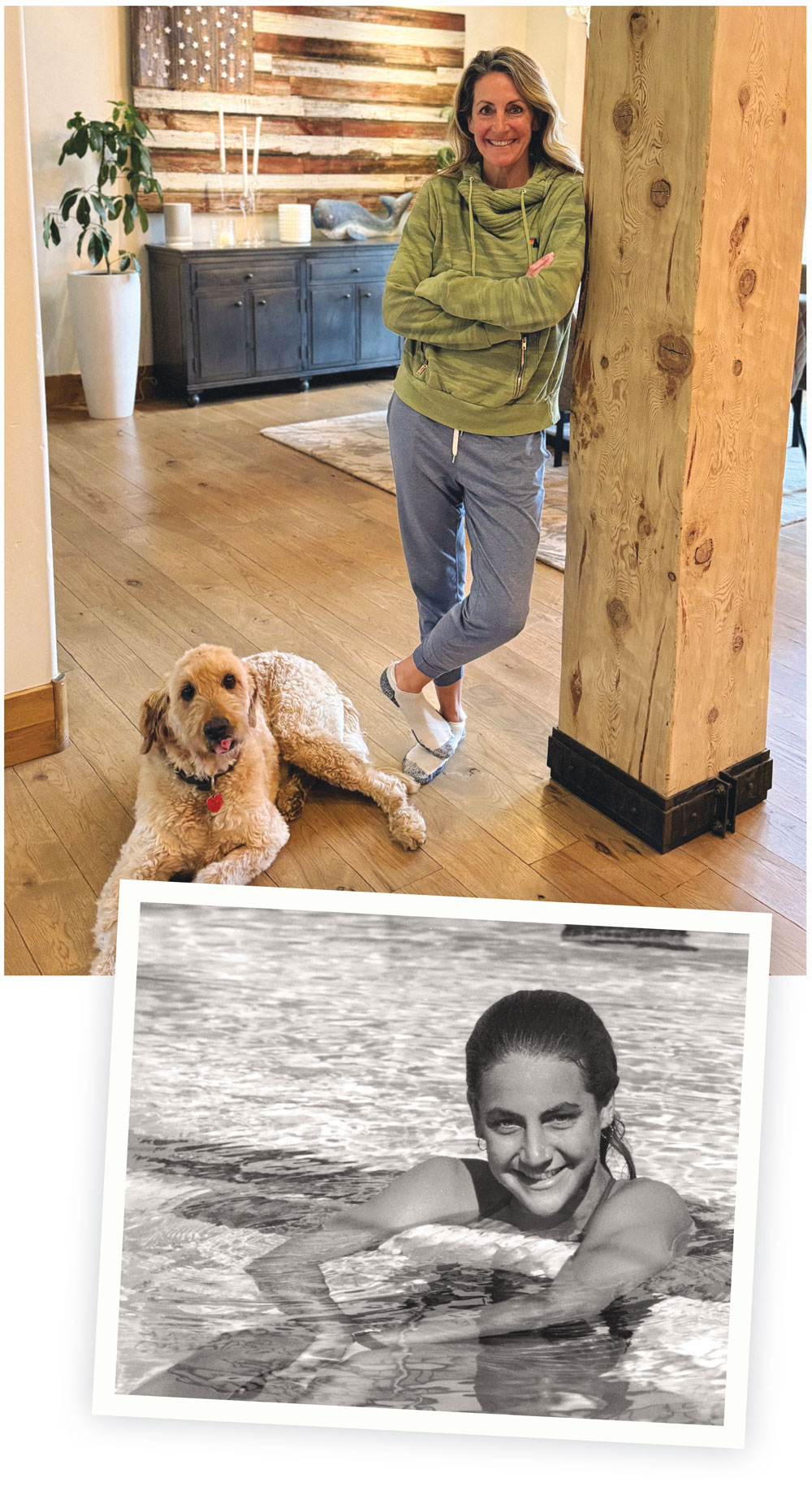

Summer Sanders, ’94

Stopped out: 23 years

Why: Post-Olympic opportunities

Today: Sports commentator, spokesperson, and philanthropic ambassador

Summer Sanders won 10 NCAA national championship titles in her two seasons swimming at Stanford, then gained international fame when she won four medals in the 1992 Olympic Games. After Barcelona, she took off one quarter from Stanford, then returned to campus as the most decorated swimmer of the Games. Resuming student life kept her grounded, she says. “It was a lot to handle. I would only do media on Wednesdays. My roommates would always answer the phone. They were the difference makers, to be honest.”

For the next two years, Sanders juggled celebrity and college courses while launching a career as an NCAA commentator for CBS. She walked with her class at Commencement in 1994 but wasn’t technically done.

“At first, I wasn’t that worried,” she says. “I knew I was coming back.” But even after summer courses, she was seven units short—and by fall, she was busy working in L.A. Her career in television was taking off. She was already co-hosting MTV’s beach game show, Sandblast; then she was an NBC analyst and host for the 1996 Olympics; and the gigs kept coming. But that unfinished business hung over her head. “There was always the ongoing stress of, ‘When am I going to fit this in?’” Plus, there was a smidge of pressure. “My dad just couldn’t understand. ‘How can you not get your degree?’” she says. “Which of course, I wanted to. It was just fitting it into life.”

As it turned out, the question wasn’t when she’d do it; it was how. “I had to wait until online classes became a thing.” In 2017, married, raising two children, and traveling for work, she was able to graduate with her communication degree by transferring online credits from the University of Utah back to Stanford. When it finally happened, she thinks she was more excited than her dad. “I knew he was proud of me, but I think in the end I did it for myself.”

INDIVIDUAL MEDLEY: Sanders finished her last lap with online credits. (Photos, from top: Summer Sanders (2); ISI Photos)

INDIVIDUAL MEDLEY: Sanders finished her last lap with online credits. (Photos, from top: Summer Sanders (2); ISI Photos)

By the NumbersWhat we know about the 8,000-plus stop-outs who crossed the finish line |

|

6.5

Years, on average, from matriculation to graduation ●

69

Years it took the longest stop-out to graduate (1942–2011) ●

269

Average annual stop-outs completed by those who entered with the classes of 1997–2024, as compared with 19 per year for the classes of 1930–1996 ●

902

Bachelor’s degrees completed by stop-outs in their most frequently chosen major, computer science (the runner-up: human biology, at 627) ●

5

Alums who stopped out before CS became an undergraduate major in 1986 and returned to get a degree in it |

Tracie White is a senior writer at Stanford. Email her at traciew@stanford.edu.