The year 1935 was good to American 60-somethings—assuming you weren’t already dead, which, statistically, you probably were. But if you weren’t, the passage of the Social Security Act set you up to be among the first to receive Old Age and Survivors Income benefits—aka Social Security retirement income. The plain-English deal to American workers was this: You contribute payroll taxes to OASI; the government pools those taxes together; Uncle Sam cuts you a monthly check when you reach that sweet, sweet age of 65. You, having avoided the grim reaper this long, could expect to live 13.7 more years, enjoying grandchildren or dancing the foxtrot or whatever retirees did then. Economic security, huzzah!

But we are in 2026. Most of us born after 1960 will survive to—and well beyond—our new and improved retirement age of 67. In 1940, when the first checks rolled out, 6.8 percent of the nation was 65 or older. Today, 18 percent are over that particular hill. So many people living so long is causing some epic funding problems. In a recent policy brief, Andrew Biggs, a fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and an expert on Social Security reform, and John Shoven, a professor emeritus of economics and a senior fellow emeritus at SIEPR, laid out a partial solution—one they believe most people could get behind.

|

You Are HereIn 2026, Social Security is largely running the same playbook it did at its creation: one with a bias toward single-income marriages; a fertility rate about double what it is today; and a lifespan that we’ve busted through like Jell-O. How It WorksThe government doesn’t sock away the 5.3 percent of your paycheck that goes to OASI (and the matching 5.3 percent that your employer pays, plus another 0.9 percent from each of you for Social Security Disability Insurance) into a personal savings account that waits for the day you sign up for midday water aerobics. It’s a pay-as-you-go system—taxes paid by today’s workers fund today’s retirees. There have always been more workers (OASI income) than retirees (OASI spending), so reserves built up. But retirees are closing the gap. “It’s so dependent on demographics,” says Shoven. “That is, how many retirees are there compared to how many workers are there? And if people are living longer and fertility rates are low, it doesn’t work nearly as well.” According to projections, in 2033, our spending will still be increasing, our income will continue to fall, and our surplus will be gone— necessitating reduced payouts unless something changes.

|

|

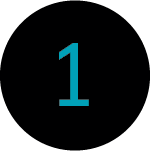

The amount a person gets in Social Security income depends on two things: • Your income while you were working (a wage-indexed average of your 35 highest-earning years). • And the age at which you claim Social Security. You can receive Social Security as early as 62, but your benefits go down for each year you claim prior to your full retirement age (up to a 30 percent reduction if you claim at age 62). Going the other direction helps you: For each year you don’t draw on benefits up to age 70, your checks go up by about 8 percent.

|

|

Social Security’s benefit formula is progressive: It’s designed to give higher returns on lower earnings. As you move up the income ladder, you’re likely more able to save on your own with 401(k)s or other investments.

If you claimed Social Security in 2024 at age 67, for the first $926 (in average indexed earnings) you had made per month, you’d receive about 90 percent in retirement benefits. This is called a replacement percentage.

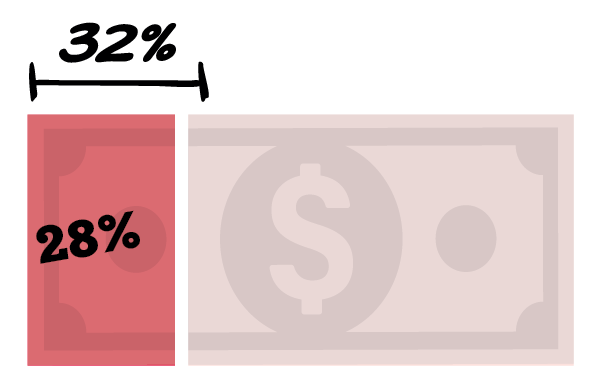

For the next tier ($927 to $5,583 per month), the replacement percentage would be 32.

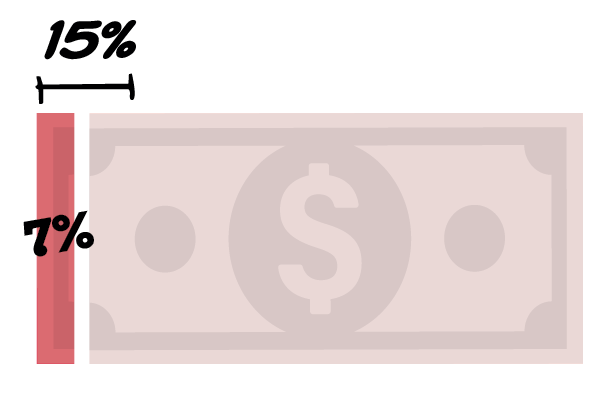

For the next tier ($5,584 to $14,050) the replacement percentage is 15. That’s the point at which OASI benefits max out. (Relatedly, those still in the labor force in 2024 paid Social Security taxes on up to $168,600 in wages—or $14,050 per month.) |

|

Show Me the MoneyThe average retired worker receives about 40 percent of preretirement income. This added up to about $1.3 trillion in 2024.

|

|

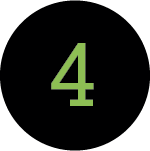

Problem Part 1: Living Too LongIn 1940, when the first Social Security retirement checks went out, remaining life expectancy as of age 65 was about 13.7 years. Today, remaining life expectancy at age 65 is, on average, 20.5 years. But it’s not equal across incomes.

|

|

Problem Part 2: Fewer Buns in Our OvensThe U.S. fertility rate has dropped from 3.6 in the baby boom years to an all-time low of 1.6 and is projected to stay there through 2100. |

|

RIP, Trust FundIn 2033 (give or take a few months), the OASI reserve coffers will be empty and, without reform of the program as a whole, a $26.1 trillion funding gap will develop over the rest of the 21st century. We did the math. In 2033, the eldest . . . • Boomers are still at the party. 87 years old • Gen Xers are retiring just as the money runs out. That tracks. 68 years old • Millennials finally own homes. Maybe? 52 years old • Gen Zers aren’t speaking to the rest of us. 36 years old • Gen Alphas are . . . probably merged with AI, right? 20 years old Déjà VuIn 1983, we faced a similar problem. Part of the solution then was to gradually raise the age at which workers are eligible to receive full benefits from 65 to 67.

|

|

OK, Boomer. What Are Our Options?Stick our fingers in our ears and sing.This is the course we’re on. The reserves will run out, and our shrinking worker ranks won’t be able to keep up. The way the law works, Biggs says, Social Security “can’t borrow, it can’t raise taxes on its own.” So, in this scenario, benefits would immediately be cut—for all retirees, not just new ones—by about 23 percent. Sorry, Nana! Raise the tax cap so that high earners pay more into Social Security. (In 2026, $184,500 in earnings are taxed.)Any solution is likely to raise the cap a bit, says Biggs. But the way he sees it, raising it dramatically would make it politically tougher to increase taxes for other societal priorities, such as infrastructure or education. “All this comes down to not just what you think should happen within the system, but it’s taking into account the fact we have all these other pots on the stove.” OMG just raise the retirement age, then.Sounds egalitarian, but this disproportionately harms the lowest earners, who would end up working more years to correct a kale-fed longevity “problem.” “They’re not living longer, so why should they have to work longer?” says Biggs. Raise the retirement age and adjust the progressivity of the formula to compensate lower earners.This is what Biggs and Shoven propose. It would get us about halfway to a fix. The rest would need to come from other measures. “We wouldn’t be [recommending] this if Social Security was in great shape,” says Shoven. “But Social Security’s got a huge budgetary problem. Most of the Republicans think we should do it with benefits cuts. Most of the Democrats think we should do it with tax increases. We think the politically realistic thing is probably half and half.”

|

|

Shoven and Biggs propose raising the age at which individuals receive their full benefits to 69. They’d also change the replacement percentages:

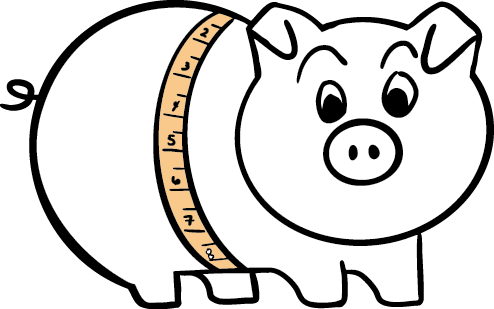

For the first $926 earned per month (using 2024 figures), the replacement percentage would be 106 percent. If you’re a lower earner, you’d get the most support from OASI.

For the next tier ($927 to $5,583), the replacement percentage would go down to 28 percent.

For the next tier ($5,584 to $14,050), the replacement percentage would decrease to 7 percent. |

|

The Fine PrintThe time is nigh. Ideally, the policy would be gradually implemented over years (as was done after 1983). The policy would only apply to workers newly drawing on benefits. So, if you just celebrated the big 6-7 by setting fire to your work pants, you’re good. Both Biggs and Shoven say they’d design the system differently if they were starting fresh today. Shoven likes the idea of progressive price indexing—keep the wage-index approach for lower earners but shift to the price index—i.e., what things cost—as you go up the income scale. Wages typically increase more than prices do over long periods of time. “If wages triple and prices double, then we triple” benefits for lower earners, he suggests. “What if, for the well-off, we said, you’re only going to get double?” Biggs would create a minimum benefit—a strong safety net at the bottom. “We’re a rich country. There’s no reason you have to have seniors living in poverty,” he says. But overhauls don’t often get traction when a crisis is afoot, and the two scholars say something needs to be done urgently. “Since [the Clinton administration], we’ve known roughly when this is going to happen and how bad it’s going to be, and we just kicked the can down the road,” says Shoven. “And I think the realistic thing to think is that, you know, we’re probably not going to fix it until it’s broken, completely broken.”

|

|

The OutcomeUnder Biggs’s and Shoven’s plan, a lot of people would work longer. (You could still start collecting Social Security—with a pretty steep hit—at age 62.) But low-wage workers wouldn’t be penalized. In fact, they could still retire at age 67 and get the same benefits that they would today. The middle class would take about a 13 percent hit—which they could make up by working to 69. Wealthier workers would get a 26.7 percent benefits cut. They’d need to work for about four more years to receive what they would under the current formula. But hey, they’re the ones who are practically immortal. |

What do you think of Biggs’s and Shoven’s proposal?

Summer Moore Batte, ’99, is the deputy and digital editor of Stanford. Email her at summerm@stanford.edu.