Water Ways

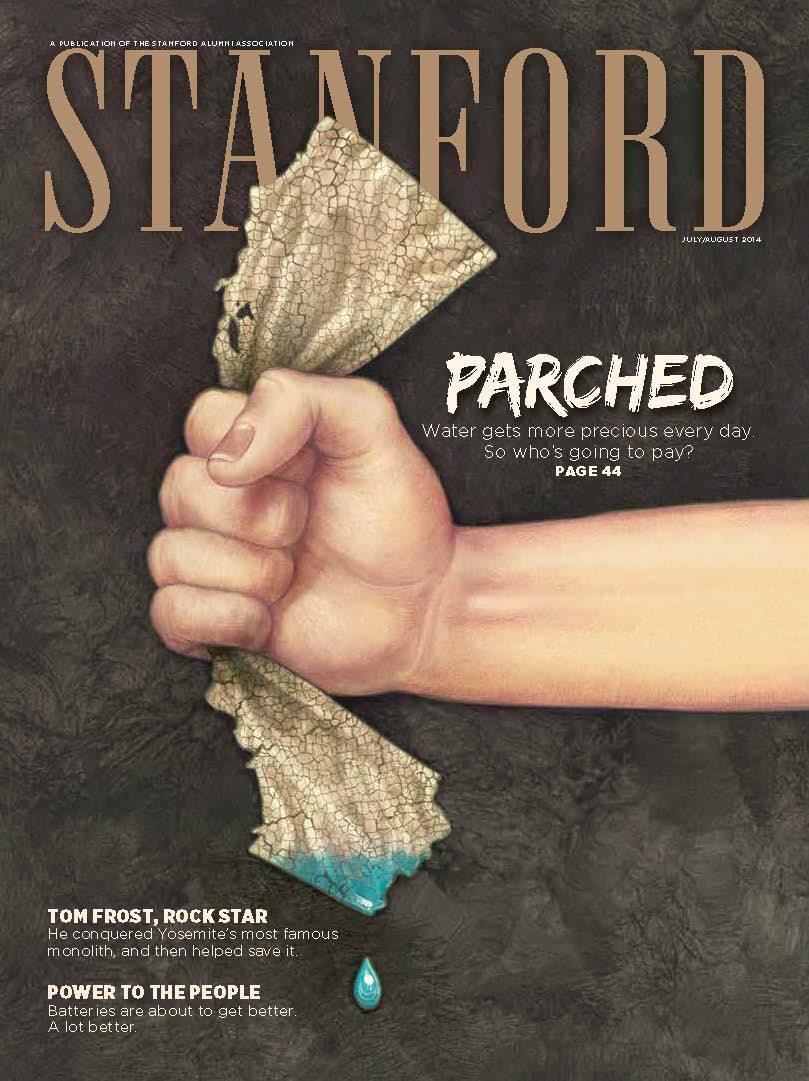

It surprises me that an article such as Kate Galbraith’s “Tapped Out” (July/August), about the water crisis in California, can comprise thousands of words addressing demand for water with essentially zero words about supply. Perhaps I can provide an alternative perspective.

California is a dry state, to be sure, but there is also no shortage of water, should we want to increase supply instead of constricting demand. For example, in Carlsbad, a desalination plant is under construction and will go online in 2016. It will produce 18 billion gallons of water per year, at a competitive price, and supply 7 percent of the residential water consumption in the San Diego Metro area. The site is environmentally friendly and especially easy on the eyes, requiring six acres of coastal land and buildings only 35 feet high.

Another 150 plants could provide all water for California businesses and residences and increase water supply in California by 10 percent. If the state were committed to balancing all perspectives, including increased supply, it would not be hard to envision a 20-year plan to build desalination plants at 100-mile intervals up the entire California coast.

Another perspective not provided by the article is the restriction of supply. There was a single oblique reference to barring farmers from their expected allotment of state water; this refers to the 2007 decision by Judge Oliver Wanger to divert 150 billion gallons of water annually into the Sacramento River delta, water that was otherwise earmarked for agriculture. Why will this water run down the drain instead of being used to irrigate crops or supply homes? To spare the delta smelt, a 2-inch fish that fishermen call bait.

The decision to remove from supply such an enormous amount of water, in an already dry state, was not the reasoned result of a deliberative process but a controversial political decision with very clear losers: California farmers. Agricultural lands lie fallow in our Central Valley not because of a shortage of water but because of an abundance of government regulation and brazen environmentalists. I note that eight desalination plants would replace this diverted water.

The state of California is not “tapped out.” We can increase supply in addition to, or in lieu of, reducing demand. We just have to have the political will to battle entrenched environmental interests to succeed. And while we almost impulsively refer to water as a “precious” resource, let’s remember that water is renewable and readily available to coastal states such as California at reasonable cost.

Tom Hernandez, ’78

Encinitas, California

The amount of water on Earth is the same now as when it and the Earth were formed; we can neither create nor destroy it. Nature controls the amount of water available at any given time in any given location, and the form that it is in: liquid, solid or vapor.

Consequently, there are land areas of the Earth that are subject to drought at times and abundant precipitation at other times. The only natural bodies of water on Earth that are truly drought-proof are the oceans.

As human beings, we are capable of trying to help nature by building dams, reservoirs, aqueducts, pumping stations, treatment plants and pipelines to capture, purify and move water around. In California and elsewhere on Earth, we have survived severe, lengthy droughts in the past largely because of the help we have been able to give nature.

As neither creators nor destroyers of water, we need to limit our role as consumers and advance our role as recyclers by controlling our own numbers before we exceed our natural water supply. This nexus between population numbers and available water supply, drought or not, cannot continue to be overlooked.

Ralph Wagner, ’52

Lake Arrowhead, California

The practice of trading water rights, described as “not commonplace” in the article, is old news in northern Nevada. The conversion of water rights from agricultural to municipal use through an orderly state transfer process has been done here since the 1950s. In the late 1970s—a drought period—a rule was imposed in Reno-Sparks requiring that water rights be purchased and deeded to the cities as a condition for obtaining a building permit. Water rights are also purchased and transferred for water quality enhancement, instream flows, wildlife habitat and other environmental purposes.

There is a robust market for water rights in Reno and other northern Nevada communities that have adopted similar rules. The system hinges on water rights being well defined and sellers being constrained from substituting another source, usually groundwater. It works for us.

Janet R. Phillips, ’74

Reno, Nevada

“Tapped Out” appears to advocate the same old solution of soaking the public financially. While Galbraith correctly points out the extent of the problem, she seems to advocate doing more studies and taxing water consumers more than governments already do. The article is simply more of the same old excuses, and the solution is no solution at all.

[Professor Thompson] points to the Irvine Ranch Water District as a successful example of a tiered pricing system. Having been on Irvine’s first planning commission and the second city council, I feel that Galbraith has completely missed the reason that Irvine’s water consumption is so much less than other communities’ in California. Since the late 1960s or 1970s, the IRWD has been reclaiming its water. While officials claim that the reclaimed water is pure enough to drink, in the ’70s they were reluctant to mix it with the drinking water. The utility used the reclaimed water on parkways and in many parks scattered throughout the city of Irvine. Of course Irvine’s consumption of water is far less than that of most other communities in the state. It has nothing to do with a pricing mechanism that encourages people to save water by not taking showers or flushing those low-water toilets two or three times in order to get rid of solid waste. Let’s face it: If Irvine people had really reduced their use of water, you could measure it only by checking on the increased use of deodorant.

Irvine’s water reclamation contrasts with the practices in Northern California. Sewage is reclaimed in Sacramento and is then dumped into the Sacramento River. The fish get clean water while the water company raises fees (taxes) on human consumers. Then the politicians blame it all on the demands for more water by Southern California water users.

The article seems to say we should cut back on water to the farmers in the Central Valley, one of the most productive agricultural areas of the world. Hmm. While the politicians are willing to spend billions on a bullet train that goes from nowhere to nowhere, one of the longest coastlines of any state is ignored. California borders on the largest body of water in the world. Unfortunately, with some of the brightest minds in the world working in California, we don’t hear that anyone is working on ways to take advantage of the huge amount of water available to us. We hear more from the politicians about how they can get out of town quickly than we hear about anyone working on or creating a financial mechanism for extracting water from the Pacific Ocean.

We need new priorities, and we need new leadership in Sacramento—people willing to attack the real problems in California. We need people whose answers are new technologies, not new taxes and fees.

Robert West, ’61, MBA ’70

Sacramento, California

As I enjoyed reading the well-written and well-researched article on California’s water problems, some additional thoughts came to mind. It is not only the indiscriminate, unmetered water use by some consumers, be they city dwellers or farmers; there is also, I believe, generally a lack of understanding of water usage by various segments of agriculture. For instance, going south on Interstate 5, the area west of the aqueduct utilizes sprinklers and much of the water is wasted, evaporating before it reaches the ground. On the other hand, judicious orchard flooding on the east side of the aqueduct practically utilizes all the water. Further, consider two major industries: California’s viticulture and milk production. Much of viticulture utilizes drip irrigation, probably the most efficient agricultural water usage. Compare this with California’s dairy industry, with more than 1.7 million milk cows, each consuming 25 to 50 gallons of water per day plus water requirements for cleanup and processing.

I have no doubt that California will see declining water availability for the foreseeable future; it seems mandatory for the state to develop a realistic water policy immediately. Such a policy must be developed on a nonpartisan basis to be accepted by all affected parties.

Ernest Glaser, MBA ’55

Walnut Creek, California

The conversations about water taking place today are largely focused on water development/transfers, flood protection and, as a distant third, habitat. My thanks to the efforts of the American Whitewater and American Rivers organizations, but despite their efforts, public recreational interests are either ignored or contained. As with groundwater, the law does not match what the developers and flood control interests would have us believe.

Under the navigable servitude doctrine in California law, the general public may be on any navigable water and on the temporarily dry land below the ordinary high-water mark for lawful recreational purposes, including hunting, fishing, picnicking, birding and presumably off-road motor vehicles. Navigable means susceptible to use even in small motorized craft. Under the public trust doctrine, public agencies are obligated to refrain from unnecessarily interfering with the public’s use of these public trust lands, and to consider the interest of the public in all planning efforts. Additionally, old decisions are subject to reconsideration. Under the California Constitution’s “right to fish” provision (Art. 1, Sec. 10), the state must retain access rights for the public when it transfers land. And the public has a right to fish from and on public land, and to fish in water the public has planted. That is the kind of legal status quo that developers and flood control interests hope will be forgotten.

Of course, recreational users are witnesses to what is actually happening on our rivers, and so preserving these rights contributes to transparency as society rethinks water allocation rules.

Francis Coats, ’72

Yuba City, California

Kate Galbraith’s thoughtful and timely article on California’s diminishing freshwater supply misses two critical points. First, California has the eighth-largest economy in the world, an industrial powerhouse manufacturing everything from agricultural products to microchips. All these industries require large amounts of water in their production, and all are constantly looking for ways to increase production, customers and profits. The impact of business growth translates directly to increasing freshwater demands far exceeding any conservation measures that residential communities can provide. Of course, the 900-pound gorilla in the room is population—both in California and worldwide. California has seen dry periods before, but humanity’s ever-growing roster has reached a level that is unprecedented. This is the underlying problem of our so-called “drought” that for some reason can never be addressed. But unless we do, there is no other solution that cannot be overrun by the next wave of thirsty citizens and corporations. It may very well be that diminishing water resources above and below ground present hard limits to growth, exceeding energy shortages in their impact on civilization. This could be humanity’s waterloo. It’s that serious.

Curtis Wilbur, ’74

Carlsbad, California

Thank you for the informative article about California’s water crisis. I just wanted to mention that a Stanford Alumni Consulting Team (GSB alumni) has been working with the California chapter of The Nature Conservancy to figure out how to engage the broader business community in developing a sustainable solution that balances the needs of people and nature. While some interests have presented this as a zero-sum game between crops and endangered species, The Nature Conservancy believes that with groundwater reform, smart conservation practices and flexible water infrastructure, there is enough water to go around.

My fellow ACT volunteers include my team co-leader Russell Hamilton, MBA ’01; Mary D’Agostino, MS ’99; Bill Ferry, MBA ’71; Nancy Girard Garrison, MBA ’73; Jessica Mennella, MBA ’00; and Aaron Ratner, MSM ’06. We’ve interviewed companies in a range of industries that are managing water impact on their supply chain, expansion plans or footprint in the community and would be happy to introduce you to the water team at The Nature Conservancy.

Cynthia Dai, MBA ’93

San Francisco, California

Perhaps I’m suffering from an excess of memory and a deficiency of compassion, but California has had ample warning. Given the drought of 1986 to 1991 and all the pontificating at the time, what kind of political malfeasance is it that there are still “some 255,000 homes and businesses in 42 communities” (including many in Sacramento!) that have no water meters?

I can answer that one. Water meters and billing systems cost money, money that California politicians have instead spent buying votes with feel-good social programs, juicy benefits for public employees and “cheap” water for the last quarter century.

Small wonder that many in other drought-stricken states, even the occasional Stanford alum, don’t really care if California runs out of water. Between misguided environmental religious fervor, the failure to learn from experience and a general lack of common sense, you will have done it to yourselves, also going broke in the bargain.

Too bad produce and wine prices will probably rise for the rest of us as a consequence.

David L. Gilmer, ’69

Kerrville, Texas, and Pinetop, Arizona

A six-page article on California’s dire water situation and not a mention of the elephant in the room: the volume of water flushed from the [Sacramento-San Joaquin] Delta through San Francisco Bay to save the delta smelt. Typical political correctness.

Kenneth G. Coveney, JD ’72

Alpine, California

Kate Galbraith argues that California has reached a water supply “crossroads.” Culprits include spreading drought, climate change and faltering aquifers; advocated are reforms in public works and government regulations. What needs attention, instead, are three crossroads encountered decades ago. A wrong turn was taken each time.

One mistaken detour was the ownership shift from private enterprise to public works. Irrigation water was provided privately before 1900. Gold rush companies built sophisticated works conveying water from Sacramento River tributaries to hydraulic mines. Angelenos bought water from the Los Angeles City Water Company until 1903; San Franciscans patronized the Spring Valley Water Company until 1930. Private enterprise works well.

Officials turned to public ownership during the early 1900s. Los Angeles built the Owens Valley project; San Francisco constructed Hetch Hetchy. Imperial Irrigation District took over the Imperial Valley works; Metropolitan Water District built the Colorado River Aqueduct. The Bureau of Reclamation constructed the Central Valley Project; the Department of Water Resources created the State Water Project. These projects were impressive. But their appeal waned. The issue today is privatization.

The second errant turn was superimposing government regulation upon the common law. The latter rose in England a thousand years ago; 13 colonies received it; 50 states, including California (1850), adopted it. It controls economic activity by precedents, actual disputes resolved in appellate opinions. Under property rules, a court can apportion available water among right holders to prevent groundwater overdraft. Contract rules facilitate ag-to-urban transfers. Tort rules resulted in the judicial shutdowns of hydraulic mining in 1885. The common law is effective.

During the progressive era, California created powerful new agencies. The Public Utilities Commission adopts prohibitions and mandates controlling water suppliers. The State Water Resources Control Board regulates water rights. The surge came in the 1970s: clean water, environmental impacts, wild and scenic rivers, endangered species. California recently initiated hydrologic controls on greenhouse gas emissions. Now the drums beat for groundwater regulation. These rules usually prove unnecessary or counterproductive. The option is deregulation.

The third wayward path, taken in the 1930s, was a shift from judicial review to judicial restraint in challenges to political interventions in the economy. Traditionally, the legal analysis was straightforward. Judges compared the relevant constitutional clause with the challenged law; they were consistent, or not. Judicial review provides the benefits of constitutional order, with moderate oversight costs.

Then judges discovered judicial restraint. They presumed interventions valid; they deferred to politicians; scrutiny was minimal. During the drought of the late 1970s, San Joaquin Valley farmers purchased all the water they were entitled to. During the current, comparable drought, they are offered none. This is due not to lack of precipitation, let alone climate change, but to new solicitude for wildlife habitat. Such actions warrant careful court oversight. At issue is abandoning restraint and reinstating review.

William M. Smiland, ’64

Los Angeles, California

Mystery Climber

I enjoyed the article in the July/August issue about Tom Frost and his accomplishments both on and off the rock face of El Capitan (“Sheer Focus”). Here’s a nod to a very important member of the team that succeeded in establishing Yosemite Valley’s Camp 4 on the National Register of Historic Places, identified in your article as “a lawyer with no real experience in the area.”

As an alum with dual, but not divided, loyalties (I got my JD from Boalt Hall at you-know-where), I write to identify that unnamed lawyer. He is Richard Duane. Upon graduating from Boalt in 1964, Dick went to the South to join in the civil rights struggle. He returned to Berkeley and practiced as a trial lawyer in the Bay Area for decades, often trying challenging cases no one else would take.

Dick took up rock climbing well into middle age. He approached it with the passion and joy that he brings to everything. He climbed El Cap and other iconic Yosemite walls and spires, becoming integrated into the climbing community in the process. It is not surprising that Tom Frost turned to Dick Duane when litigating against the Department of the Interior seemed the only way to save Camp 4 for posterity. Dick never shied away from a tough climb, whether on vertical granite or in the courts.

Bill Larkins, ’77

Portland, Oregon

Safeguarding Fisk’s Masterpiece

I had the fortune to be the structural engineer who seismically retrofitted Mem Chu in the early ’90s (“Power and Glory,” July/August). Perhaps the most challenging part was bracing the Fisk and Murray Harris organs. I spent many days carefully crawling in and between the pipes, some as large as my waist, others as small as a finger, mapping them out and calculating where to place braces that would protect the organs in the next earthquake while being completely hidden from view and not affecting sound quality.

One of my proudest engineering accomplishments is that anyone can walk into the church today, look at the organ, and see only the great masterpiece of Charles Fisk.

Evan Reis, ’87, MS ’88

Atherton, California

Greek Drama

I must offer some corrections to the letter written by Anne Jacques (“The Bigger Picture,” July/August).

The stories I was told about how the sororities were finally dissolved came from family members who lived through those years of disagreement, two of whom were my great-aunt Mary Curry Tresidder (wife of President Donald B. Tresidder) and her sister, my grandmother Marjorie Curry Williams. These stories are presented in the excellent Stanford Historical Society book by Edwin Kiester Jr., published in 1992, Donald B. Tresidder: Stanford’s Overlooked Treasure. The history of the sorority controversy can be found on pages 5-6, 55-58 and 112.

Mary Yost, dean of women at that time, could never have been the one person to “decide that the process was discriminatory and . . . [have] abolished them.”

Quoting the book, the few sororities had been “a fixture at Stanford almost since the founding. They were regularly challenged as undemocratic and exclusionary, but they survived—until 1944.” The disputes would reappear, then subside, until early 1943, when a petition presented by 13 women (six were sorority members, seven were not—reflecting the fact that even the sororities themselves were not in agreement) “urged the trustees to choose one of two alternatives. Either enough new sororities should be authorized so that every woman who wished to join could do so, or sororities should be abolished completely.”

The issue filled the letters column of the Daily for more than a year, with “manifestoes, petitions, position papers, and statements” filling meetings and conferences on the calendar. However, “All proposed reforms were merely cosmetic,” according to Tresidder, who had himself “run out of ideas.”

Since even the Panhellenic Council had failed to “come up with a workable compromise solution,” with the backing of the Trustees, Tresidder announced on April 20, 1944, that “sororities at Stanford will cease to exist as of July 1, 1944.”

“He later called it ‘the most difficult decision of my presidency.’”

During my own pre-reg week in 1962, it was fun and interesting for me to meet a few of the daughters of some of the women who had been on one of the committees back in the early ’40s that had strongly recommended that the existing sororities be abolished. Every single woman sitting in that 1962 group (and in many others over the next four years), when asked why they’d chosen Stanford, said, “Because there are no sororities here!”

My grandmother, a devout Theta, never quite got over the fact of the dissolution!

The very difficult decision made ultimately by “Uncle Don,” as he was affectionately called by many on campus, was, of course, the result of years of discussion and attention to the issue by many students, faculty, the administration and the trustees—and could never have been decided by only the dean of women, as important as Dean Yost surely was.

Robin Curry Williams, ’66, MA ’67

Hillsboro, Oregon

I have been interested in reading the letters to the editor on the story of discrimination at the fraternities years ago. My experience was a little different. We had Jewish members in Phi Gamma Delta, and I do not recall it being an issue. What we didn’t have were Democrats. We conducted a straw poll for the famous 1948 Truman-Dewey election. The result from our 50 members: Dewey 48, Truman 0 and Henry Wallace 2.

Ed Wright, ’50

Atherton, California

An Ambassador’s Agenda

Robert L. Strauss’s article about Professor Michael McFaul’s ambassadorship to Russia offers an intriguing glimpse into America’s current foreign policy (“A Chill in the Air,” May/June).

In his 2001 book entitled Russia’s Unfinished Revolution: Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin, McFaul was quite critical of Putin’s governance. McFaul added an extra helping of criticism in his 2008 Foreign Affairs article, “The Myth of the Authoritarian Model: How Putin’s Crackdown Holds Russia Back.”

What was the real objective in sending McFaul to Russia in 2012? There was clearly no mutual affection between Putin and McFaul. Was he sent as an ambassador to Russia, or as a highly visible Putin critic, or as a community organizer to encourage Russian activists to continue their struggle against Russia’s alleged social evils and to implant America’s human rights agenda?

Has traditional decorous diplomacy been replaced by lecturing, posturing and pressuring those countries unwilling or unable to bow to Washington’s enlightened elitism? Or was this just a trial precursor to “international organizing”?

Donald Keene

Edmonds, Washington

I’m too old to have met Michael McFaul at Stanford, though I have no doubts about his intellectual powers, the quality of his education or his qualifications as a professor. What I have doubts about are his qualifications as ambassador, especially to Russia. Moreover, I have serious doubts about the wisdom of appointing him to the position. There is the old saying about a little knowledge being a dangerous thing. McFaul’s studies in Russia notwithstanding, I’m afraid he has very little knowledge about Russia as a country of over a thousand years. His time spent there on his earlier visit did not seem to have enlightened him much. My opinion is that as an ambassador, he was a disaster.

When will America learn not to be the “professor of the world,” let alone its policeman? When will it learn that the U.S. model is not necessarily a model to fit all and sundry? When will this naiveté get exorcised from the thinking of American administrations, Democratic or Republican? When will we stop preaching to one and all about “democracy”?

Most important, when will the United States recognize that teaching by example is far and away the better method? How can a state teach others anything about running a country when it tolerates the wholesale ownership of assault weapons by its citizens and the resulting mass killings? How can we teach people about freedom and democracy when our clandestine institutions spy on citizens, often contrary to law, not to mention constitutional restraints? [The United States is] a country that tortures its prisoners. A country that holds people against their will in places like Guantánamo Bay, without charging them, without trying them—all on the shaky ground of their being “suspected terrorists.” (If they are suspected, why not charge them and try them, according to law and the Constitution?) The list goes on.

The world is a complex place. I can’t believe that, in light of the history of the last 50 years, McFaul can say—innocently enough—“The world suffers when the United States is not involved”! Indeed, as experience has shown time and again, the world suffers when the United States sticks its nose into places it has no business being.

Adam von Dioszeghy, ’64, JD ’70

Budapest, Hungary

Desperation?

I was interested to read Sam Scott’s article on the new book by Sean McMeekin, 1914: Countdown to War (“In the Trenches, Digging Deeper,” May/June). The book, Scott agrees, has not gone unchallenged by the vast majority of historians who place the primary responsibility for the war at the door of Kaiser Wilhelm, but Scott himself does very little challenging of McMeekin. McMeekin blames the Russians for their “haste to mobilize,” ignoring the fact that Russia in 1914 was a lumbering elephant compared with the central powers and could not match any of the powers in rapid mobilization.

In a side column, we read an excerpt from McMeekin’s book that Sam Scott again chooses not to challenge: Germany “was indeed the Power that first violated neutral territory in Luxembourg and then in Belgium. She did so, however, out of desperation, out of Moltke’s belief that only a knockout blow against France would give her the slightest chance of winning.” Winning what, one might ask. A war of aggression, fought largely in France and Flanders. But Germany, writes McMeekin, was “desperate.” Again Scott makes no comment. Germany had no choice. For the second time in 44 years, it just had to invade France. Out of sheer desperation.

David Wingeate Pike, PhD ’68

Paris, France

War: A Conversation

Francis Fukuyama makes the excellent point that the development of centralized states may not have been and may not ultimately be as “productive” as claimed by Professor Ian Morris (“On the Spoils of War,” July/August). For example, is there any doubt that the creation of the U.S. national security establishment has proved to be an extremely unproductive development? But this issue is a matter of philosophic propensity and thus has no “correct” answer.

The glaring, purely factual error in Morris’s hypothesis concerns the irrelevance of his claim that violent death is far lower today than during the Paleolithic, roughly 2 million to 10,000 years ago (what Fukuyama refers to as the “hunter-gatherer times”). While the claim itself is supported by the archaeological evidence, this evidence does not in any way support the professor’s hypothesis.

During the Paleolithic period, life expectancy of male pre-humans and subsequently homo sapiens increased from approximately 20 to 35 years. Thus, during this entire era the majority of the male population consisted of what today we refer to as “teenagers,” that is, testosterone-driven, risk-taking and prone-to-violence males. It is not surprising, then, that a larger percentage of the population died from violent causes during these many generations.

As our species began to live longer and the stabilizing influence of grandparents became common (starting around 35,000 years ago), the percentage of population consisting of daredevil teenage males declined rapidly. Fewer risk takers as a percentage of population translates naturally into fewer people dying of violence.

I suspect that if Morris were to analyze his data on the basis of percentage of teenagers who died violently during the Upper Paleolithic compared with the percentage of teenagers who die violently today, there would be no statistically significant difference.

With the advent of agriculture and the rise of cities during and after the Neolithic, more people started dying from contagious diseases and “old age” (cancer, heart failure, etc.) than during the Paleolithic. As a matter of mathematical certainty, this means that a smaller percentage of the population was dying from violence. The advent of what we call nation-state wars had nothing to do with this shift in percentage of deaths by violence.

Finally, the very nature of violent conflict has changed. During the Paleolithic, small bands competed directly with other small bands, resulting in entire groups of all ages being killed in territorial combat. When walled towns/cities protected by professional soldiers arose during the Neolithic, entire populations were usually not slaughtered during periods of armed conflict. Today we have available weapons of such vast destructive power that if they were widely used there would be virtually no humans left on the planet. Thus, the potential for death by violence today is hundreds of times greater than during the Paleolithic. The only reason these weapons have not been used is the deterrent effect of mutually assured mass destruction, not the nature of war itself.

In short, correlation does not prove causation. The advent of organized violence (war) merely coincides with the decrease in percentage of deaths by violence. Professor Morris has yet to prove a causal link.

James Luce

Peralada, Spain

Professor Morris replies:

Thanks for your message and your interest in my book. I haven’t seen Francis Fukuyama’s review yet, but I do have to disagree with some of the points you make. There’s a lot we don’t know about the Paleolithic world, but we do know a great deal about ages at death, and there’s no evidence at all for an increase in life expectancy at birth from 20 to 35 years. Life expectancy varied from place to place, because some sites were healthier than others, but the average figure remains firmly in the low 20s from the earliest evidence we have until very recent times. Life expectancy at birth only reached 35 in Sweden shortly before 1700; in England soon after that date; in France around 1830; in the Netherlands around 1840; in Italy around 1880; in Spain around 1905; and in Russia perhaps around 1910. (I take the figures from Massimo Livi-Bacci’s Concise History of World Population and Population of Europe.)

Life expectancy at birth above 30 is a very modern phenomenon, driven partly by the decline in violent death among adults, more so by public health measures (especially clean water) and chiefly by falling infant mortality. The percentage of teenagers didn’t decline greatly anywhere before the 18th century, and if grandparents did exercise a stabilizing influence (and I’m not certain that they did—my own granddad was a very rough character), it didn’t kick in until the 19th and 20th centuries. Even then, it was initially limited to industrialized countries. You also suggest that a higher proportion of the population started dying from old-age illnesses after the beginning of farming, but the evidence again suggests the opposite. Overall, life expectancy declined slightly almost everywhere in the first millennium after farming began, probably because diets became narrower. Some archaeologists (Keith Otterbein is the most influential) also think that rates of violent death in fact rose after farming began, but on the whole the evidence seems not to support this.

Thanks again for your email, and I’ll be interested to hear if you still feel the same way if you have a chance to read the book.

James Luce replies:

Thank you for the prompt (not expected) and intelligent (expected) reply to my letter. My analysis is based in part on two Scientific American articles (scientificamerican.com/article/the-evolution-of-grandparents/ and scientificamerican.com/article/caspari-

neandertals-and-the-first-grandparents). As with much of our understanding of the distant past, there is room for disagreement and further research. That is, after all, what the scientific method is all about and what makes science so exciting.

I do enjoy your hypothesis that war can be productive and look forward to reading your book and also the forthcoming work by Francis Fukuyama. It seems to me that you two could form the nucleus of a very interesting symposium on the Nature of Man . . . Past, Present, Future.