One day during his senior year, Keegan Livermore, ’16, took a break between classes to go to Green Library in search of a dictionary of a little-known, nearly extinct language spoken by his ancestors on the Yakama Indian Reservation in central Washington.

“I couldn’t really believe this dictionary for this relatively small language could even be there,” says Livermore, a comparative literature major who was planning to be a teacher. “To think that the Yakama Nation was even on Stanford’s radar was very surprising to me.” After finding the dictionary listed in the catalog, he made his way up the stairs to the third floor and started rummaging between the narrow-aisled stacks piled high with books.

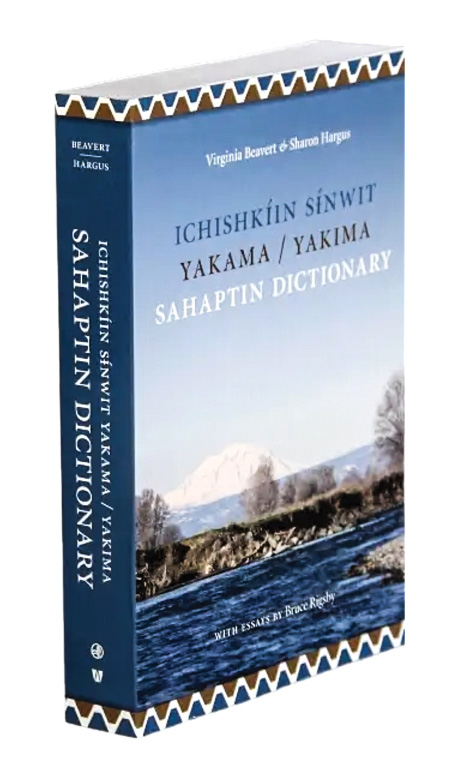

There it was, an unassuming 576-page dictionary of what linguists call Sahaptin, known as Ichishkíin in the language itself. Excited to see the written language for the first time, Livermore flipped through the pages, noting the modified Latin alphabet with extra marks and accents. It was totally unfamiliar to him, and yet learning it seemed vital—at the time, only a few dozen people still spoke the Yakama version of Sahaptin fluently. “Well, of course, I thought, this is what I’m going to do next.”

He returned to his dorm and set about figuring out how to read, and someday even speak, this language that has been evolving for 4,000 to 5,000 years in what is now the Northwest United States. Two years later, Livermore had graduated and was living on the Yakama reservation in the town of Toppenish, studying the language and making good on a goal that had begun to form that day in the library: to help save the Sahaptin language and bring it back to life on the reservation.

First, learning

Livermore grew up in Portland, Ore., roughly 100 miles from the tribal community where his great-grandmother—a Yakama elder who died when Livermore’s mother was 2 years old—was born and raised. Cecelia Sohappy grew up speaking Sahaptin as her first language, but she never taught her children, and the language died out in his family. Livermore learned little about his Native culture growing up—his father is white, of European descent, and his mother is Filipino, Yakama, and European.

“I wanted to explore it when I got to college,” he says. As a sophomore, he chose to live in the Native ethnic theme house, Muwekma-Tah-Ruk, and volunteered to help organize the annual Stanford Powwow. As an entering Stanford student, he thought he’d major in physics but after his junior year switched to comparative literature. “I was in a class where I was reading a lot of books in translation and learning the joys of reading something in its native language,” he says. “I had the idea, since I’m doing this a lot with Western literature, maybe I could do a version of that for my tribe.”

He found his way online to Virginia Beavert, a Yakama elder and a linguist at the University of Oregon. She’d co-authored the Sahaptin dictionary Livermore found in Green that day, and she was one of a group of linguists studying and teaching its newly written form. Livermore began learning everything he could about the language. It was spoken by tribes across the Northwest and had multiple dialects. And it had been nearly wiped out by the federal government’s Indian boarding school policies, which stretched from 1819 until 1969 and caused tens of thousands of Native children to be removed from their homes and sent to boarding schools to assimilate. “They were extinguishing their home languages and replacing them with English, making them wear uniforms, cutting their hair, converting them to Christianity, abolishing Indigenous religious practice,” says Gregory Ablavsky, a Stanford law professor and an expert on the history of federal Indian law.

But in the 1970s, on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement, a nationwide effort was afoot to save endangered Native languages. Preservationists such as Beavert’s stepfather, Alex Saluskin, reinvigorated efforts to develop a written version of Sahaptin. Beavert carried forward his efforts for many years. When she died in 2024 at the age of 102, the Wall Street Journal called her the woman “who preserved a language the U.S. tried to erase.”

His comparative literature degree in hand, Livermore embarked on his first master’s degree—in language arts and linguistics—at Heritage University, a private college on the Yakama reservation where Beavert had once taught. He also started eating deer meat and salmon at ceremonies (he had been a vegetarian at Stanford), hanging out with his grandmother’s cousins, whom he calls his “aunties,” and going to dig for roots, a traditional food. For his thesis, Livermore chose a project that involved dissecting the parts of Beavert’s memoir that were written in Sahaptin. (She wrote the memoir as her PhD dissertation, which she completed at the age of 90.) He examined word order, the structure of the sentences, and the syntax, while conducting a word-by-word translation. “I was figuring out how the word order was chosen,” he says. “I’m a grammar person. There was a lot of translation, which helped build my translation muscle, though I felt a bit like I was building the train tracks while riding the train,” he says, laughing.

Like many Native languages, Sahaptin is a highly synthetic language that can convey complex ideas within a single word—what other languages might do in several words or a short sentence. These long words contain many prefixes and suffixes used in various orders to create new meanings. Sentences differ from English’s structure of subject, verb, object. Livermore’s thesis helped show that what appears to English speakers as random word order actually follows specific patterns. For example, whether the subject gets repeated in a sentence depends on how long ago it was mentioned.

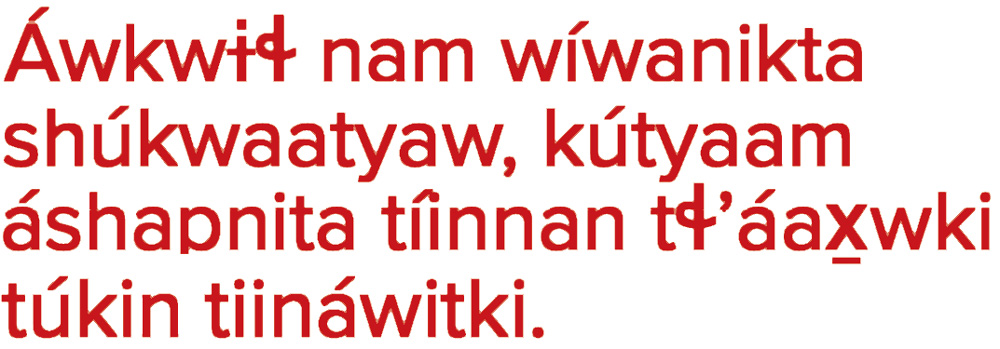

Translation: You can only ask a book so many questions, but you can ask a person pretty much anything under the sun.

In 2019, Livermore left the reservation and went to the University of Oregon to earn a second master’s degree, in language arts and teaching, and to create a portfolio of work to support a teaching credential. He received some of his training there from Beavert and found the in-person instruction to be pivotal. “You can only ask a book so many questions, but you can ask a person pretty much anything under the sun,” Livermore says. “Learning from someone who had dedicated their life to preserving and sharing this language, in addition to getting a PhD in her 90s—that’s pretty inspiring.” It helped solidify his knowledge of Sahaptin. “Two master’s degrees later, I’m pretty good at reading it and I can speak it,” he says. “I’m a solid intermediate.”

“There is nothing like these languages,” says Janne Underriner, a research associate professor who was one of Livermore’s instructors at the University of Oregon. “Their morphology is complex; there’s a freeness to the word order. It takes changing your mind about learning a language. You have to live in ambiguity and be comfortable with it. It takes considerable devotion. It’s why Native language teachers, like Livermore, are heroes.”

Then, teaching

When Livermore started studying Sahaptin, only about 35 of his tribe’s 11,000 enrolled members spoke the language fluently, a number that has since declined further. “A number of fluent speakers have passed away since I’ve been here,” he says.

During his second master’s program, Livermore developed a curriculum framework for teaching high school language classes, which was convenient because he had already accepted a position to teach Sahaptin to eighth through twelfth graders on the reservation. Livermore taught for two years, from 2021 through 2023, soaking up information about the culture from the children of the tribe while at the same time developing new teaching materials and sharing his technical knowledge of—and passion for—the language. “I was teaching six classes a day at the tribal high school, where Sahaptin is a requirement,” he says. “These kids come from all over the reservation. Some had learned bits and pieces of Sahaptin. Some wanted to learn more of their Native language and cultural education.

“I was trying to bring in a lot more conversational practice into the classroom,” he says. “I tried to be creative—like, I translated a couple of games, including Guess Who? ” The class would play together, learning vocabulary, grammar, and conversation along the way.

There isn’t a set curriculum that Sahaptin teachers use—they all have to create, curate, and adapt materials to fit their needs, says Allyson Alvarado, a fellow Sahaptin teacher on the reservation. “A lot of times, elders who were not familiar with technology or creating teaching materials taught these classes. When I first met [Livermore] and learned he was going to be involved in teaching language, I thought, thank goodness. He’s super organized and gets things done, and he’s tech savvy.” He even developed a cell phone keyboard for Sahaptin that she and other teachers now use regularly for texting.

“He created one for iPhones and Androids, which is crazy,” she says.

In late 2023, Livermore transitioned into a position that had become his dream job: strategic planning manager for the Yakama Nation Language Program, which supports reservation-wide efforts to revitalize Sahaptin. He commutes 30 miles each day to his job in Toppenish from his home in Yakima, which he recently bought with his partner, Adam Wilson.

Bringing a language back to life is not an easy thing to do, but that is literally his job description. And yet, by its nature, it’s a team effort with many others across the reservation.

“In my current role, I take a step back,” Livermore says. “I’m working on the planning side with seven different school districts that have [Sahaptin] language teachers.” He helps create cultural activities in the community as well as translations for learning about Native practices. Activities include bringing students out into the hills to dig up bitter root and bread root while speaking about it in Sahaptin, and translating public health posters—how to wash your hands, for example—into Sahaptin and posting them in public spaces. He also works with several outreach coordinators to sift through the tribe’s archival materials and make recordings of them in Sahaptin to share with the reservation’s residents. The idea is to bring the language into the community, into homes, and to make it fun and accessible, he says.

“I’m excited now to hear people use the language more in public, with each other,” he says. “I’m excited to hear people joke around with each other in the language, really reconnecting with it and taking it into their hearts and enjoying it.” It’s especially vital, he says, for children, whose knowledge of Yakama culture provides a sense of pride and self-worth.

Alvarado, too, is beginning to see this reemergence of the language on the reservation. “It’s teaching us a lot about our tribe and our ancestors, the animals, the landmarks,” she says. “I have a 1-year-old. It’s so important to teach our babies, our kids.”

Tracie White is a senior writer at Stanford. Email her at traciew@stanford.edu.