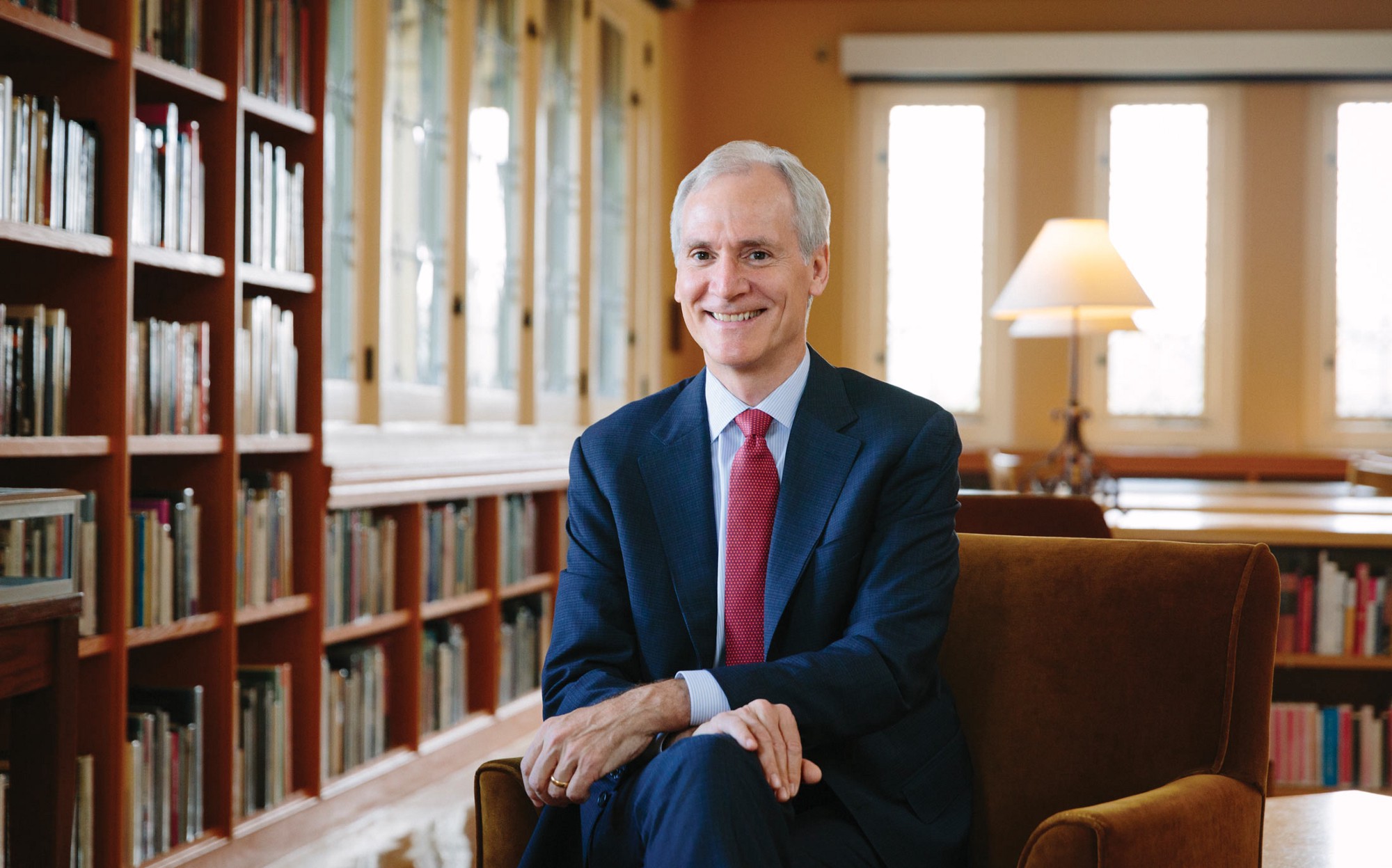

When Marc Tessier-Lavigne began as Stanford’s president two years ago, he noted that the university was already strong and well positioned for success. The challenge before him and the rest of the community, he said at the time, was determining “what better looks like.”

To answer that question, Tessier-Lavigne set in motion a long-range planning process, inviting ideas and proposals from all members of the community. A three-month input period produced more than 2,800 submissions, including more than 500 from alumni. In May, the university published “A Vision for Stanford: Navigating a Dynamic Future,” which will help set the agenda for the next several years. It lists a set of priorities in four areas, each involving three or four initiatives:

The university faces no shortage of challenges. Decreased federal funding requires finding new sources of support for research. The high cost of living in the Bay Area threatens Stanford’s ability to attract and retain faculty and staff. Issues such as free speech and sexual assault have galvanized students and led to fresh discussions about university policies.

In an interview with STANFORD, Tessier-Lavigne discusses these matters, and how the long-range planning process will inform the university.

The long-range planning process you initiated was broadly inclusive. Why did you want so much input?

MTL: Well, we didn’t know how much we would get, of course, when we started. We actually had bets leading up to the deadline, and all the bets clustered around 1,000 ideas and proposals. We were really taken aback when we got 2,808, and half of them came in the last 24 hours.

We wanted to get community input because we just have extraordinary people on campus, and you want to tap into all the brilliance that’s there. We also solicited opinions from outside perspectives — thought leaders from higher education, from foundations, from government, from business, just to pressure-test things.

We tried to prompt people to think about different ways we could get better by asking for input in four categories: advancing frontiers, strengthening foundations, stimulating synergies, and anticipating change and how it should inform our thinking about Stanford.

For example, in the case of education, what new technologies are coming to life now that might be fully enabled five or 10 years from now? What should we be doing to anticipate that? How should we think about virtual reality or augmented reality as we think about education?

How did the priorities materialize?

MTL: In many cases, what we got was an affirmation of things that we sort of had a sense were important. For example, one of the messages that came through was a desire to have more flexible and nimble funding mechanisms [for research] to be able to go deep in certain areas, to take on risky new directions. That’s certainly something that was on our radar but to have it come through loud and clear from the community amplified our perception. We also got many novel and unexpected proposals. The priorities materialized by synthesizing all the input and asking which initiatives would enable us to maximize our impact on research and education. The process also helped us identify potential leaders in various areas, people who put in ideas and proposals. So, beyond simply helping us identify priorities, it helped us connect those priorities to members of the community whom we could call upon to help us develop the priorities.

What are the implications of having a more nimble and flexible funding infrastructure?

MTL: We wanted to make sure that we could maintain a robust research enterprise across the board. We’re in a period of constrained funding. This led us to propose seed grants for new and risky ideas. We are also putting in place what we are calling pioneer grants to take discoveries to the next level, to scale them. Often, it’s to create a new resource or a new instrument for other researchers that can enable our community broadly.

A lot of the requests that we had were for resources to build knowledge communities, where you can bring together people who are working in the same general field but who don’t have a venue for retreats, for poster sessions, for seminar series. There was also strong interest in creating shared resources and infrastructure. Historically, libraries are an example of a “platform” that benefits research overall. Similarly, in biomedical research, we have advanced microscopes that no one faculty member can own and operate, that you have as a resource for all faculty.

A lot of this is about the plumbing of research. It’s unglamorous because it’s not about any specific subject, but all researchers know that by providing those resources, you enable a thousand flowers to bloom.

In addition to that, of course, there are some thematic areas that came through loud and clear, that dovetailed with our sense of what was important in the world today. That led to eight research initiatives in four categories that we believe are areas of high impact where we see huge opportunity and huge need.

The initiative on human-centered artificial intelligence seems to be one Stanford could lead, given its history in technology transfer. Could you talk a little about that?

MTL: There is a revolution going on right now and especially in the last five years in machine learning, enabling machines to take over tasks that previously only humans could do. The holy grail in AI is having [a robot] look at a picture of a cat and know it’s a picture of a cat. Machines can now do that. And the applications are enormous.

Take medical diagnosis. An algorithm has been developed at Stanford to look at skin lesions and determine whether they are malignant or pre-malignant. Is this a melanoma or a carcinoma, or is it just a benign skin lesion? That can be done now more accurately by a machine than by many specialists.

This is the second industrial revolution that’s being enabled by data sciences and artificial intelligence right now. It’s going to change our lives profoundly.

There are practical and ethical considerations for the applications of these technologies, and we have to think through the potential consequences on society. Driverless vehicles are being enabled by artificial intelligence and the use of sensors, and this has the potential to be profoundly enabling to society on one hand, but to reconfigure the job landscape for people on the other. Getting ahead of these societal consequences of those developments is important. So, the artificial intelligence initiative involves both trying to maintain Stanford at the leading edge of technology development, but equally making sure that the technology is human-centered, that we control the robot rather than the robot controlling us.

The cost of living in the Bay Area continues to put major pressure on Stanford’s ability to attract and retain faculty and staff. Realistically, what can Stanford do to mitigate those concerns?

MTL: It is a big issue and one that we really have to tackle. The approach that we’ve taken is two-pronged. The first was to roll out some near-term initiatives to help. For faculty, an immediate step was to augment our mortgage programs [which include low-interest loans and other benefits to enable housing purchases]. And then for staff, an enhanced salary program, an expansion of the satellite work program, the work-from-home program. These are all just near-term things that we can do, essentially with the stroke of a pen.

But we know that’s just a beginning. We have to do more, but we’ve realized we don’t have a good sense of what the range of needs is — they are different for different people. We don’t want to put in place the wrong solutions.

So, we thought it was better to put together an affordability task force that includes all those different elements: salary, benefits, transportation and housing. By the second quarter of 2019 they’ll have to come up with recommendations that we expect will be different for the different subpopulations of our campus community.

We are asking the task force to think boldly because the magnitude of the problem is sufficiently great that incrementalism is not going to do the job.

The nature and quality of intellectual discourse is a recurring theme nationwide, and there are new efforts at Stanford to foster dialogue across the ideological spectrum. How is that going?

MTL: Fostering a diversity of opinions on campus is essential to Stanford’s mission. We would not be serving our students well if we did not expose them to different opinions so they can think for themselves what their position is on the issues.

A diversity of opinions is essential for research as well. We know that to get at the truth you often have to consider the unpopular issue or an idea that may appear silly to some. Think of theories like quantum mechanics that were very counterintuitive at the time, or general relativity. It’s true in the social sciences as well.

One of the things that we did to try to promote dialogue was to create the series Cardinal Conversations, where we brought together speakers who had divergent views on consequential issues and could model respectful disagreement. And I’d say we had some success, and we learned some lessons from the first experiment this year. The very first of these was a debate between [PayPal cofounder and tech investor] Peter Thiel [’89, JD ’92] and [LinkedIn cofounder] Reid Hoffman [’89], two individuals who have a lot of mutual respect but who disagree profoundly on many issues. Our students were fascinated, and many of their questions were along the lines of, “How can you be such good friends, given how different your political views are?”

[Thiel and Hoffman] said that when they met [as undergraduates] they each had a similar motivation to understand the other: “Why does this really smart person have such views?” I think our students learned as much from that as from anything that they will learn at Stanford. That said, we realized that for the Cardinal Conversations mechanism to work effectively, we need students to select topics they want to discuss. We’ve had some success, but there’s a lot more that we can do.

Photo: Linda A. Cicero/Stanford News Service

Photo: Linda A. Cicero/Stanford News Service

One of the goals expressed in the long-range plan is to ensure an inclusive campus climate. How do you balance that with the goal of spirited, unfettered debate?

MTL: A university, to fulfill its mission, must be a place where a diversity of opinions is promoted and enabled. At the same time, we want to be an inclusive community, and where the two can come into apparent conflict is if people feel that certain ideas that are discussed affect their sense of belonging to the institution. So, creating a culture of open exchange where we can foster a respectful discussion of divergent viewpoints is an important priority for the university.

Our students have in some cases expressed their displeasure with the invitation of some speakers, but they’ve done that in a way that wasn’t disruptive. And that’s the key thing. It’s absolutely fine for our students to protest, as long as they don’t disrupt the exchange of ideas.

We have a lot of feedback that the students want this kind of open debate, and they’ve shown that they’re eager to embrace it. And I’m very optimistic. The students themselves have been organizing debates on consequential issues as well.

Another issue that is troubling universities across the country is sexual assault. What more can be done to prevent sexual assault and to improve adjudication of sexual assault cases?

MTL: This is a hugely important issue. The approach that we’ve taken has been to focus on three areas. The first is trying to figure out how most effectively to educate our students as they come on campus, and then as they are on campus, to understand what kinds of behavior are appropriate and what kinds of behavior are not. Some of our best allies in this have been our students, who have come up with some of the best programming for New Student Orientation, for example.

The second is providing support for victims and students in crisis. And there, again, we put programs in place and we’re constantly working to improve them. And again students have been key drivers in this. For example, last year, the ASSU really championed the use of a program called Callisto, [which] is a mechanism for helping victims that we’ve implemented.

The third area, of course, is having robust adjudication procedures that are fair to all the participants. There’s been a pilot process in place now for two years, and there’s a committee that’s been receiving feedback from the community on what can be done better. And they’re going to be rendering a report in the near future.

In addition to that, we’ve recognized that adding more transparency on this issue is important. The provost put forward a report that enables everybody on campus to see the consequences and the outcomes in each case. It can serve as a deterrent for those who might think that they can get away with things, and we can monitor our progress in coming years. We can’t rest until we have completely eradicated sexual assault and sexual harassment from our campus community.

What continues to inspire you about Stanford?

MTL: The people. It’s just an extraordinary community. It’s been so exciting for me to immerse myself in meeting the students, the faculty, the staff, the alumni, and to see just how accomplished and thoughtful, but also how engaged, everyone is in the life of the community and in wanting to make sure that Stanford can be the best university it can be. And this has been further affirmed by the long-range planning process. I really think that we have the opportunity to change the world, and it’s because of the people and the culture.

What would you like to say to alumni about the university and its future?

MTL: As we start executing the long-range plan, it’s important for alumni to know that we will continue to engage them actively in all aspects of this, just as we did in the long-range planning process itself. And we’ll keep them informed. Even as we move forward with new initiatives and changes to what we’re doing, it will still be the Stanford that they love and know.