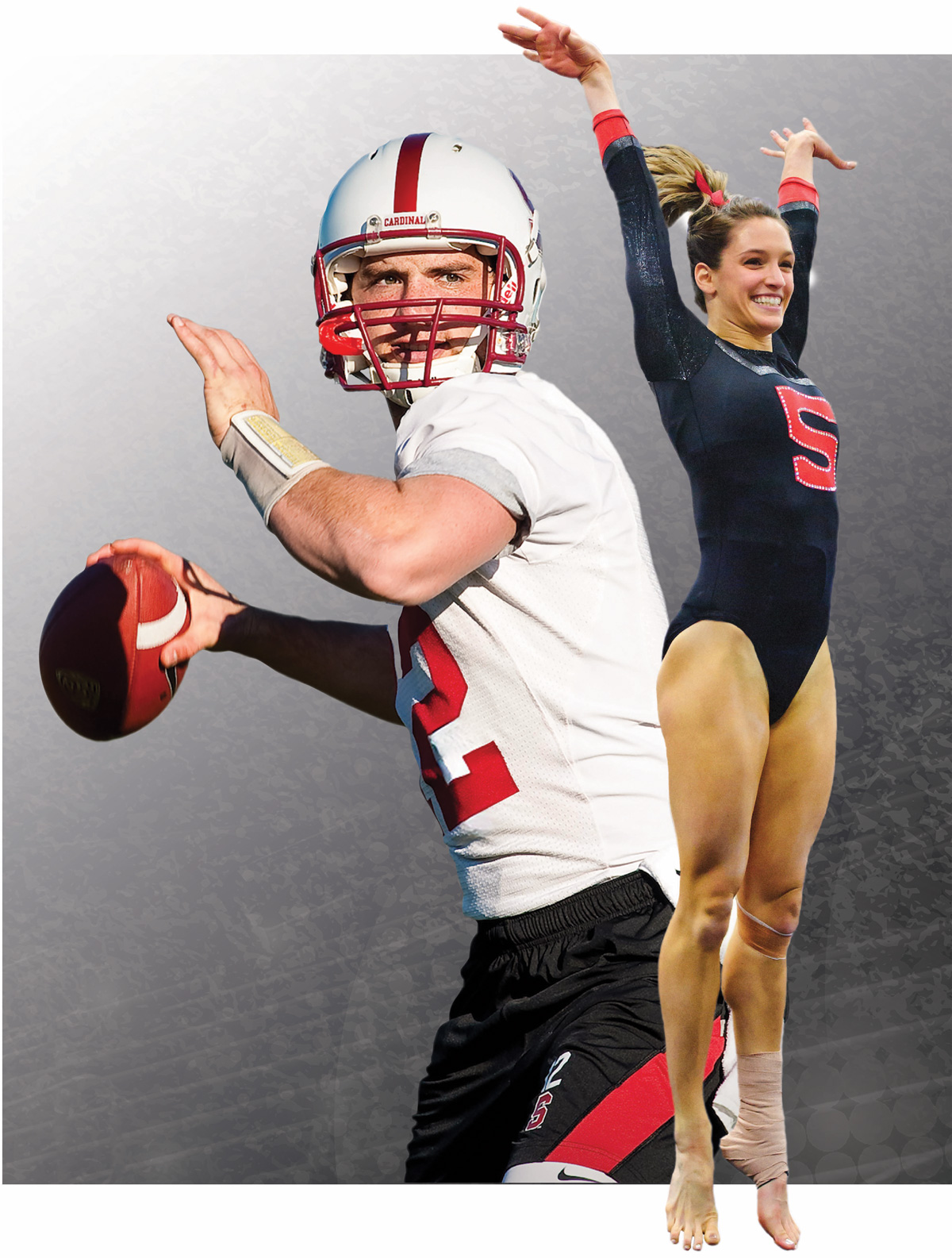

One day last October, former Stanford All-American quarterback Andrew Luck and his wife, former Cardinal gymnast Nicole Pechanec Luck, had just about put the finishing touches on the first chapter of their post-football life. Andrew’s sudden retirement from the NFL in 2019 following years of fighting injuries had left both of them emotionally spent, so they had decamped to their bungalow a short bike ride across El Camino Real from the Stanford campus.

After five years in which Nicole, ’12, gave birth to two daughters while establishing herself as an NBC Sports and ESPN producer and Andrew, ’12, MA ’23, earned a master’s degree at the Graduate School of Education while caring for Lucy and Penelope, they had decided to move closer to family. Andrew would coach high school football, for the second time leaving Stanford to begin a new career.

Photos, from left: Don Feria/ISI Photos; Rob Ericson/ISI Photos

Photos, from left: Don Feria/ISI Photos; Rob Ericson/ISI Photos

Before he left, though, Luck wanted to weigh in with new university president Jonathan Levin, ’94, about the state of the Stanford football program, which has followed 10 seasons of feast with six seasons of famine. While the numbers may not hew to the standard seven-and-seven in Genesis, anyone with an emotional stake in the fate of the Cardinal will tell you the disaster feels biblical in proportion. Stanford has won a total of 20 games in the past six seasons (2019–24) after having won 102 in the previous 10 (2009–18). The Cardinal also won three Pac-12 Conference championships and went to five major bowl games in that decade, a decade that began with the emergence of a young quarterback named Andrew Luck.

Every athlete who succeeds at the highest level of sports has a congenital case of competitiveness. The condition persists long past retirement. Luck had been feeding his hunger by getting involved with the collective Lifetime Cardinal, raising and distributing name, image, and likeness (NIL) money for Stanford athletes. But the Cardinal’s lack of success on the field gnawed at him. Luck winced as Stanford struggled to adjust to unfamiliar, faraway opponents in the Atlantic Coast Conference after the collapse of the Pacific-12 Conference. He watched the Cardinal play football in a nearly empty stadium. He believed that even in the new world of intercollegiate athletics, in which the players followed dollars instead of coaches and chose quality of contract over quality of education, there remained athletes who want all of the above.

“I was not embarrassed, but sort of ashamed that we couldn’t deliver more for them,” he says.

Not every concerned alum can arrange a meeting with President Levin. But if you threw for 9,430 yards and 82 touchdowns in three seasons while leading Stanford to a cumulative record of 31-7, you have some cred when it comes to the football team. Luck arrived at Building 10 with a page of notes.

‘College football isn’t going away, but it’s going away as we knew it.’

“It was a bit of, ‘Hey, if I’m moving, I probably should let our new leader know, just make sure he’s aware of the existential threat football is under,’” Luck says. “I don’t mean to sound dramatic, and college football isn’t going away, but it’s going away as we knew it.”

Levin immediately put Luck’s mind at ease. The president considered Stanford Football a problem that must be fixed. “He got it,” Luck says. “He already knew it.”

Not long into the discussion—20 minutes?—Levin shifted the tenor from theoretical to practical: Would Luck want to run Stanford Football?

It had been five years since Luck had faced an unexpected blitz. He may not have seen it coming, but once a quarterback, always a quarterback.

“There was a part of me that immediately reacted, ‘You don’t have to say anything else. I get what you’re putting down, and I’ll take all of it,’” Luck says.

Then he jolted back to reality. He had a wife, they had a life, a life they had decided would no longer be in Palo Alto. Luck told Levin he would get back to him. He called Nicole. She was putting her horse, Ovour, in a trailer for the move.

“So, I just got out of a meeting with President Levin, and I think he offered me a job,” Andrew told her.

“I’m like, ‘Do I load the horse or not?’” Nicole says.

She loaded the horse, even as she knew she wouldn’t be following it.

A month later, Stanford announced its new head of Stanford Football.

“College football has a very special characteristic because there are just not that many times when you can get 50,000 people in one place cheering for your school,” Levin says. Luck’s charge is to “have a successful team, have them be successful academically as well as athletically, and to build strong community support that’s essential to sustain the football program. And he’s a natural leader. I have incredible confidence that he’s going to be successful.”

His athletic skill and probing intellect (he earned an engineering degree with an emphasis in architectural design) make Luck “the epitome of the ‘Stanford athlete,’” says Professor Condoleezza Rice, the director of the Hoover Institution and former U.S. secretary of state who has been a guiding force for Stanford Athletics throughout her three-plus decades on campus. Luck remains firm in the belief that Stanford can compete at the highest level of intercollegiate athletics without sacrificing its academic soul. They called it “intellectual brutality” during his playing days.

“I think it differentiates us from our academic peers in many ways,” Luck says. “It’s part of what makes Stanford Stanford. We compete with everybody in whatever arena it is, whether it’s academics, competing with the Ivies and MIT, or athletics, going toe to toe with Texas and Michigan and Ohio State. That’s what we do, traditionally what this place always did.”

College football has undergone radical change in the last several years. Court cases have determined that student-athletes should have freedom to hop from one campus to another and should get a greater share of the billions flowing into the college game. Stanford, with its emphasis on both sides of the hyphen in student-athlete, was slow to adapt to the new rules, recalcitrance that manifested itself in a whole bunch of 3-9 records. Luck believed that the university had to a) accept that paying players is table stakes and b) commit to continuing competition at the highest level of athletics, which meant c) accepting more transfers into the football program, at least in the short term. (Stanford—and virtually all of its athletic peers—have announced that they will share revenue with student-athletes under the June settlement in House v. NCAA.)

Luck’s title is general manager, a longtime NFL position that arrived in college football when players started getting paid. Most college football GMs manage the roster, deciding how to dole out X amount of resources to Y number of players. Most college football GMs aren’t four-time Pro Bowl quarterbacks and the most popular player at their school in a generation. In addition to the typical duties, Luck has immersed himself in marketing the team, selling season tickets, and even taking part in a few spring practice drills. His self-assessment? He may have lost a step.

“They needed someone to hand off, so I did it and I had way too much fun. Way too much fun,” Luck said. “I’m not [taking snaps] under center with our guys, though. I can’t move fast enough to get away.”

President Levin also granted Luck the power to hire and fire the head coach. Luck used the latter authority in March to dismiss Troy Taylor after two seasons. Luck cited the need for change and referred to the university’s two investigations of Taylor’s behavior as an administrator. He had never fired anyone before.

“I didn’t sleep very well for a few days,” he says. “But I felt full agency and ownership over it, and the decision was what I believe was best for where we were going.”

A young, inexperienced boss might have been forgiven for dithering. Luck saw a problem and dealt with it. “Andrew is showing great talent as an administrator and a leader,” Rice says. “Quarterback in the NFL is absolutely a leadership position. He was admired and followed—even as a rookie—by veterans.” Or as Nicole puts it, a smile on her face, “He’s very good at telling people what to do.”

Given that it was March, and most college football head coaches are hired sometime in the last six weeks of the previous calendar year, Luck asked a good friend to be a placeholder. Frank Reich’s first year as an NFL head coach, with the 2018 Indianapolis Colts, had been Luck’s last as the Colts’ quarterback. The longtime pro coach hadn’t participated in college football since he played quarterback for the 1984 ACC champion Maryland Terrapins.

“I didn’t say these words,” Reich says of Luck’s phone call to coax him out of retirement, “but I know I at least thought them: ‘You have flat-out lost your mind. What would ever make you think that could be a good idea?’

“But if there’s one thing I knew about Andrew, [it’s that] before he called me, this is something he thought long and hard about. And so, because it was Andrew, because it was Stanford, I just think there was a curiosity and hey, life is about experiences. This can be an incredible experience, doing something you love to do with a friend that you love and appreciate and respect at a unique place, an elite academic university.”

Reich is 63 years old. Luck is 35, still younger than NFL star quarterbacks Aaron Rodgers, Matthew Stafford, Russell Wilson, and Kirk Cousins. Luck’s hairline has taken a three-step drop from where it used to be, but he weighs 14 pounds less than his Stanford playing weight of 234.

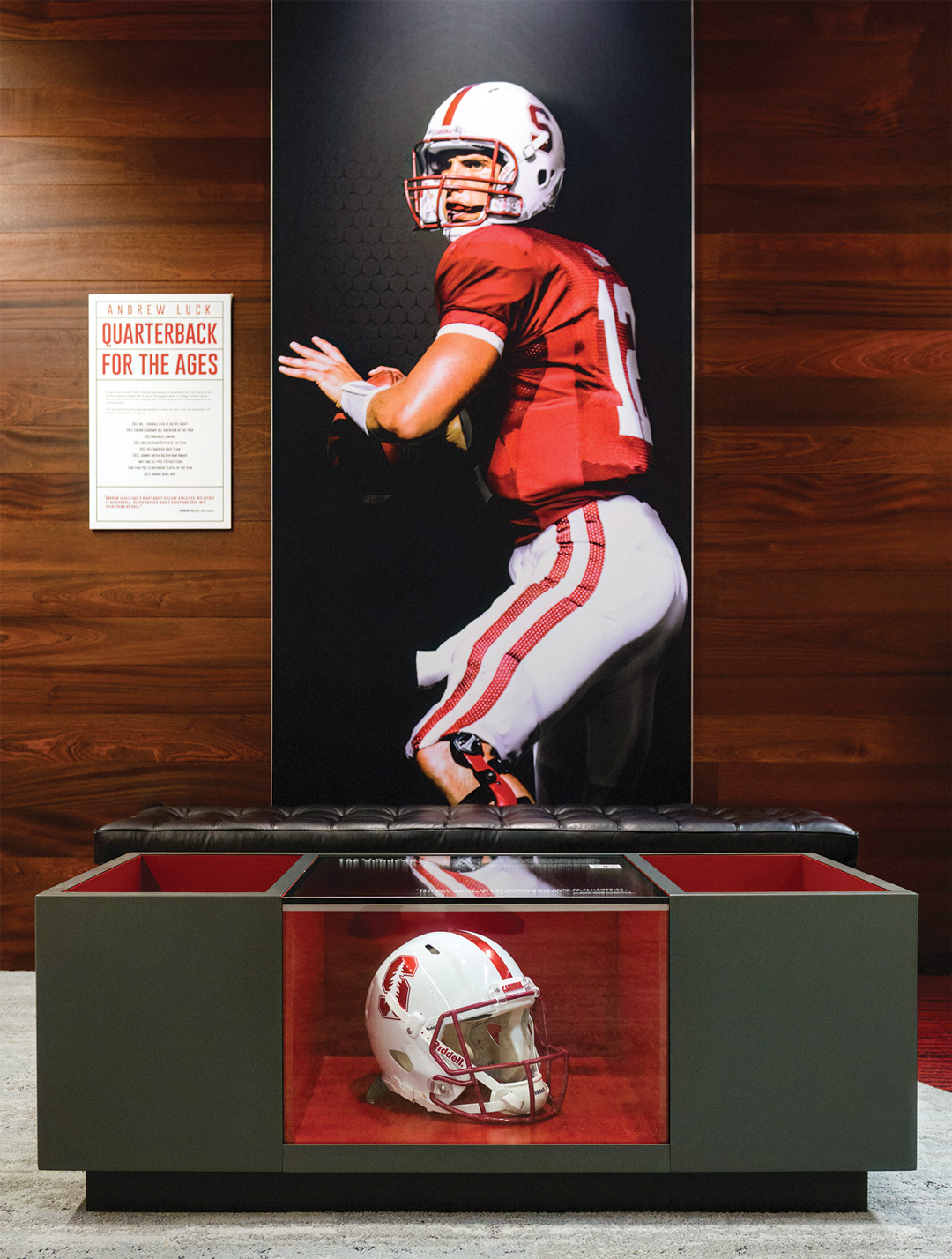

On the second floor of the Arrillaga Family Sports Center, approximately 50 feet from the door of the Stanford Football offices, there is a display honoring Luck. A large color photo of him looking downfield is accompanied by a list of his accomplishments headlined “Quarterback for the Ages.” Sitting in front of the photo is a display case in which is enshrined a Stanford helmet. On the case is printed a tribute to his classroom achievement (Academic All-American). On either side of the case are receptacles filled with books, a nod to the book club that Luck conducted while playing for the Colts.

But to enter Luck’s office itself is to be reminded that he has never bought into his own celebrity. The first piece of memorabilia Luck hung on the wall sits above his computer: a framed New Yorker cartoon he received from his mother, Kathy. Two men are seated in front of a TV screen that shows a football player in uniform, laying on a couch, his arm lifted mid-sentence. A psychiatrist, seated nearby, has legs crossed, notepad open.

“Sometimes,” one viewer says, “I think all this postgame analysis has gone too far.”

Sitting at a conference table, Luck turns and looks at the wall behind him. There hangs a framed, signed jersey of quarterback Jim Plunkett, ’70, next to a framed poster from the 1991 season, the Stanford centennial. Stanford Football, Luck says, “feels like it’s a Gordian knot worth picking at.” (According to legend, Alexander the Great solved the riddle not by picking at the knot, but by slicing through it with his sword. Intellectual brutality, indeed.)

“We’ve won two national championships [1926, 1940]. We’ve been to the fifth-most Rose Bowls in the history of college football [15]. The quarterback history here is unparalleled. The coaching history is filled with luminaries and folks who helped redefine eras of football, like Pop Warner, Clark Shaughnessy, Bill Walsh. So part of what I’m reminding myself, and I think our community, is that football has mattered here, and it’s mattered for a long time, and it’s been a part of the fabric of this university since four months after the doors opened.”

He laughs in disbelief, the enthusiasm in his voice reflecting why he was such an easy mark for President Levin.

“Part of what I view as my job is reminding people, starting with our most proximal community, that we’ve got to keep playing football at that top level. Look, we’re not Alabama or Michigan or Texas or Georgia or USC, but we’ve never tried to be them, right? We’re also not like a footnote in college football, which is what it has felt like.”

With an interim coach and no stars to speak of on the team, Luck has dived into becoming the face of the program. In the winter and spring, he traveled from coast to coast to speak to alumni groups. He enlisted the Alumni Association to hold get-togethers before road games this fall from Honolulu to Miami. “There are many challenges associated with the East Coast,” Luck says—15 of 18 ACC teams are in the Eastern time zone—“but maybe one of the few lemonades-out-of-lemons can be the fact that we’re in neighborhoods that we haven’t traditionally been.”

When Luck thinks of the 2011 Orange Bowl, a 40-12 Stanford rout of Virginia Tech that ended his 12-1 redshirt sophomore season, he doesn’t think of the four touchdowns he threw as much as the scene at the hotel afterward.

“It felt like there were 35,000 alums, just full of Stanford alums celebrating,” Luck says. “We are committed to doing an alumni event attached to every away game. In many ways, our team exists for our alums. It’s their team as much as anybody’s.”

Luck leapt into the efforts to sell season tickets, cold-calling prospective buyers the same as others in the athletic department. “Yes, this is really Andrew Luck,” he said to one. “No, this is not an AI robot, although I wouldn’t be surprised if that starts happening here soon.”

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE: Luck, above at Stanford’s ACC home opener against Virginia Tech in 2024, and below, with Nicole before his first start for the Cardinal, at Washington State in 2009, is again the face of the program. (Photos, from top: Bob Drebin/ISI Photos; Courtesy Nicole Pechanec Luck)

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE: Luck, above at Stanford’s ACC home opener against Virginia Tech in 2024, and below, with Nicole before his first start for the Cardinal, at Washington State in 2009, is again the face of the program. (Photos, from top: Bob Drebin/ISI Photos; Courtesy Nicole Pechanec Luck)

He does not hesitate to ask people for money, perhaps because he has seen it done. His father, Oliver, also a former NFL quarterback who became a collegiate and professional sports executive, once served as general manager of the Houston Dynamo in the MLS. “We’d be driving, we’d pull over, and he would walk into a business, do whatever we needed to do there, and then sell season tickets to them. What I think I internalized as a middle-school, high-school boy who idolized his dad, is that everybody sells season tickets, especially if you happen to be in charge of the thing. You just do it.”

He has met with leaders from the Stanford Band and New Student Orientation to strategize how to get students to return to Stanford Stadium. The combination of COVID and poor results have snuffed out student attendance, and now, as Luck puts it, “some of the links of ritual and tradition had been severed.” He remains appalled that not all students jump when the LSJUMB reaches the crescendo of “All Right Now.” He intends to fix that.

Then there’s recruiting, which Luck enjoys way more than he expected.

“There is a bit of the same emotion of winning a game, when a young man says, ‘Yes!’” Luck says. “Recruiting feels existential, and it’s stressful. I’d sit and ask [director of recruiting] Preston Pehrson and [assistant GM] Sam Fisher [’14, MBA ’19], ‘Should I text the kid now? He hasn’t responded. Should I text him back?’”

Luck starts to chuckle.

“Sam said, ‘Oh! You didn’t date, Andrew. You’ve never dated, huh? You have to go through what we all went through in our 20s.’”

Andrew didn’t “date” at Stanford. He and Nicole lived next door to each other as freshmen in Roble Hall. If it wasn’t love at first sight, it didn’t get much past second sight. On the day they met, he conned her into giving up her phone number by telling her he couldn’t find his phone and asking her to call it.

It’s hard to imagine two people better suited for each other. Nicole, the daughter of Czech immigrants, left home at age 12 for gymnastics training; by 17, she was competing for the Czech National Team. Nicole, like Andrew, received an engineering/architectural design degree. “If we were a company, he’d be the architect and I’d be the GC [general contractor],” Nicole says, “and that’s how our lives work. He has the big ideas, and I execute efficiently.”

Nicole, like Andrew, retired early from her athletic career because of physical pain. For her, it was her back and knee. For him, his ankle. The psychic pain they endured in private, after the spotlights trained their wattage elsewhere, can be just as arduous to combat.

“I think it’s so hard because it’s your identity,” Nicole says. “I started when I was 2. I don’t remember not having gymnastics in my life, but I also understood it’s more than just physically ending.”

Seven years after she went through her withdrawal, her husband retired because of injuries, giving up football a few weeks short of his 30th birthday. Not that understanding it made living with it any easier. “I joke that dealing with a retired 30-year-old was a lot harder than dealing with a newborn child, and I had to deal with them at the same time,” Nicole says.

Sport is a shallow partner. It may pretend to love the athlete, engage his or her intellect, reward hard work and devotion with fame and fortune. But in the end, no matter how deep an athlete’s love for his sport, no matter the devotion to her craft, the sport throws over the athlete for someone younger.

“I’m still in pain. His ankle still hurts. But it’s also so special, and it’s given both of us so much, and that’s why we love these athletes on campus,” Nicole says. “They are truly what makes Stanford special, and just giving them the resources, obviously, but also just believing in them, I think means a lot.”

A university deputizing one of its former athletes to come to its athletic rescue is an American trope. In theory, a former athlete understands the university, its mission, and its community in a way that the typical prospective coach or administrator does not. In reality, the sports world is littered with the carcasses of stars who returned to their alma maters and failed.

“I don’t want to lose my love for Stanford,” Nicole says. “But when you love something, you also have to be willing to lose it. It’s possible that it won’t work. So that is a little scary. It also means we are all-in.”

That is the GC talking. The architect doesn’t merely acknowledge that there is no guarantee of success. He embraces it. Luck committed to attend Stanford following the 2006 season, when the Cardinal went 1-11. Four years later, with Luck at quarterback, they went 12-1 and finished fourth in the nation.

“It’s sports,” he says. “That’s what’s beautiful about it.”

A New Kind of Athletic DirectorDonahoe takes over at a ‘pivotal and tumultuous time.’ |

|

The hiring of John Donahoe, MBA ’86, as the Jaquish & Kenninger Director and Chair of Athletics is both a departure from precedent and a recognition of the formidable task ahead for Stanford Athletics. Donahoe’s résumé is what most of his fellow alumni of the Stanford Graduate School of Business dream of: a long career as CEO and/or board chair of successful entities such as Bain & Co., eBay, ServiceNow, PayPal, and Nike. What his résumé does not include is coaching, administration, athletics fundraising, or as much as one step on the traditional path to becoming an athletic director. Of course, these are not traditional times. That the university added “and Chair” to the job title is indicative both of his strengths and the boardroom acumen that President Jonathan Levin, ’94, and the rest of the search committee believed the university needs. “John knows Stanford, and he has a unique blend of leadership at the highest levels along with deep business experience and relationships, most notably in sports, technology, and media,” said Stanford trustee and NBA executive Amy Brooks when the university announced Donahoe’s appointment. Brooks, ’96, MBA ’02, co-chaired the search committee with law professor emeritus and faculty athletics representative Jay Mitchell, ’80. For all of the Farm’s considerable success in athletic competition—best described by 138 NCAA championships (14 more than second-place UCLA)—the unmapped future of American intercollegiate athletics regarding student-athlete compensation and conference realignment calls for someone who can keep Stanford in the same conversation as the USCs and Michigans and Alabamas. To do so requires someone comfortable raising not a boatload of money but a whole fleet’s worth. The $20.5 million that each Football Bowl Subdivision school may share with its student-athletes annually is merely the ante. When Stanford began searching for an athletic director earlier this year after the resignation of Bernard Muir, Donahoe seemed like a perfect fit: JV basketball player at Dartmouth, MBA from the GSB, long career as a CEO, most recently at Nike, where Donahoe counted founder and Stanford benefactor Phil Knight, MBA ’62, as a close friend and mentor. Perfect fit, yet Donahoe initially demurred. He had resigned from Nike in October 2024 after a challenging four years that included the buffeting of retail during the pandemic. Donahoe, who had returned to the Bay Area from Oregon, still wanted time to decompress. The more his head cleared, the more he realized he didn’t want another conventional CEO job. Conversations with several search committee members—including Levin, Brooks, professor and Hoover Institution director Condoleezza Rice, investor Jesse Rogers, ’79, and former women’s basketball coach Tara VanDerveer, who came in clutch with a mid-July phone call—helped bring the deal together by the end of that month. “My north star for 40 years has been servant leadership, and it is a tremendous honor to be able to come back to serve a university I love and to lead Stanford Athletics through a pivotal and tumultuous time in collegiate sports,” Donahoe said when his appointment was announced. “Stanford has enormous strengths and enormous potential in a changing environment, including being the model for achieving both academic and athletic excellence at the highest levels. I can’t wait to work in partnership with the Stanford team to build momentum for Stanford Athletics and ensure the best possible experiences for our student-athletes.” Stanford is not alone in its approach. Oklahoma has enlisted former AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson as “executive advisor” to its president and athletic director. Hiring a business executive to run the athletic department is not a guarantee of success. But it does illustrate that Stanford will continue to pursue athletic excellence, a tradition nearly as old as the university itself. |

Ivan Maisel, ’81, is a writer in Connecticut. Email him at stanford.magazine@stanford.edu.