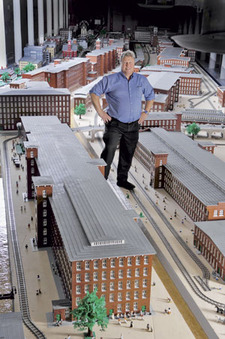

In a 19th-century building beside the Merrimack River in Manchester, N.H., Douglas Heuser presides over an unlikely empire built of 3 million plastic bricks. Some 8,000 miniature residents—fixed with perpetual smiles—look familiar to anyone who's had a child in recent decades. Most of the tiny figures re-enact the manufacturing practices of the 19th century, working in a replica of what once was one of the world's largest textile factories. However, a few in this stunning recreation of Manchester's Amoskeag Millyard, circa 1915, pursue less noble endeavors—such as a bank robbery and a way-too-believable purse-snatching.

Heuser, '71, directs the SEE Science Center, where hundreds of volunteers spent two years and 10,000 hours creating the world's largest permanent Lego installation at a minifigure scale. The replica millyard is one of the most popular attractions in this 45,000-square-foot museum.

Heuser (rhymes with user) says nothing in his academic or professional background portended that he would co-found a science museum. Born in Micronesia and raised in Minnesota, he studied psychology at Stanford, not physics or engineering. Before writing the grant that launched the science center, he toiled in the Granite State's social services bureaucracy.

But a “serendipitous” conversation with then-Gov. John Sununu put Heuser in touch with Dean Kamen, the New Hampshire inventor/entrepreneur who is best known these days as father of the Segway. Kamen wanted to start a science-education center in a mill building he owned in Manchester. SEE opened in 1986.

Heuser admits he was underwhelmed when Kamen proposed a partnership with the Lego toy company. “I just went, 'Okay, so you want us to build hundreds of buildings out of bricks that all look the same—wow, isn't that exciting?' ” Heuser remembers. “I quite frankly did not get it.”

But after visiting the Legoland amusement park near San Diego, Heuser got plastic-brick religion. He came to realize the mini-millyard could be a teaching device, not an overgrown dollhouse.

The exhibit is faithful in its portrayal of the era's work force. Women and children work alongside the Lego men. Captions explain that New Hampshire's child-labor laws eventually would prohibit anyone under 14 from working, and would limit the number of hours that boys under 16 or girls under 18 could work. As early as 1847, New Hampshire had made history by becoming the first state to limit the workday to 10 hours. The laws made it difficult for Amoskeag to compete with textiles produced elsewhere.

Running water flows through canals and a miniature Merrimack. A working railroad system chugs from the mill to the station. A section of the exhibit memorializes an amusement park in the mill complex that included a Ferris wheel, roller coaster and swan boats.

“Words do not do this project justice, and even pictures do not give you the full sense of the scope it encompasses,” Heuser says. “You really have to see it.”

Many people have: the exhibit boosted museum attendance from about 30,000 visitors annually to more than 70,000. The Lego village also broadened the SEE's demographics, enticing unaccompanied adults. “It used to be grandparents bringing grandkids,” Heuser says. “Now it's just grandparents.”

ELIZABETH MEHREN is a journalism professor at Boston University.