Luciana Frazão was so sure of rejection that she waited a week to open the email from Stanford admissions. A reminder of how wrong she was is forever inked on her hands: three bands on her left ring finger, one on her right, to symbolize 3/1/2019—the day she learned she’d been accepted to the master's program in mechanical engineering.

But the drama was only just beginning that day. Fraza˜o, a Brazilian living in Rio de Janeiro, hardly had the money to send in her visa documents, let alone pay for two years of graduate school. Neither did her single mom, a retired administrative assistant who had raised and supported three kids.

ROBOTIC ARM: A passion for testing tech through combat, plus her interest in human-centered design, led Frazao to Stanford. (Photo: Toni Bird)

ROBOTIC ARM: A passion for testing tech through combat, plus her interest in human-centered design, led Frazao to Stanford. (Photo: Toni Bird)

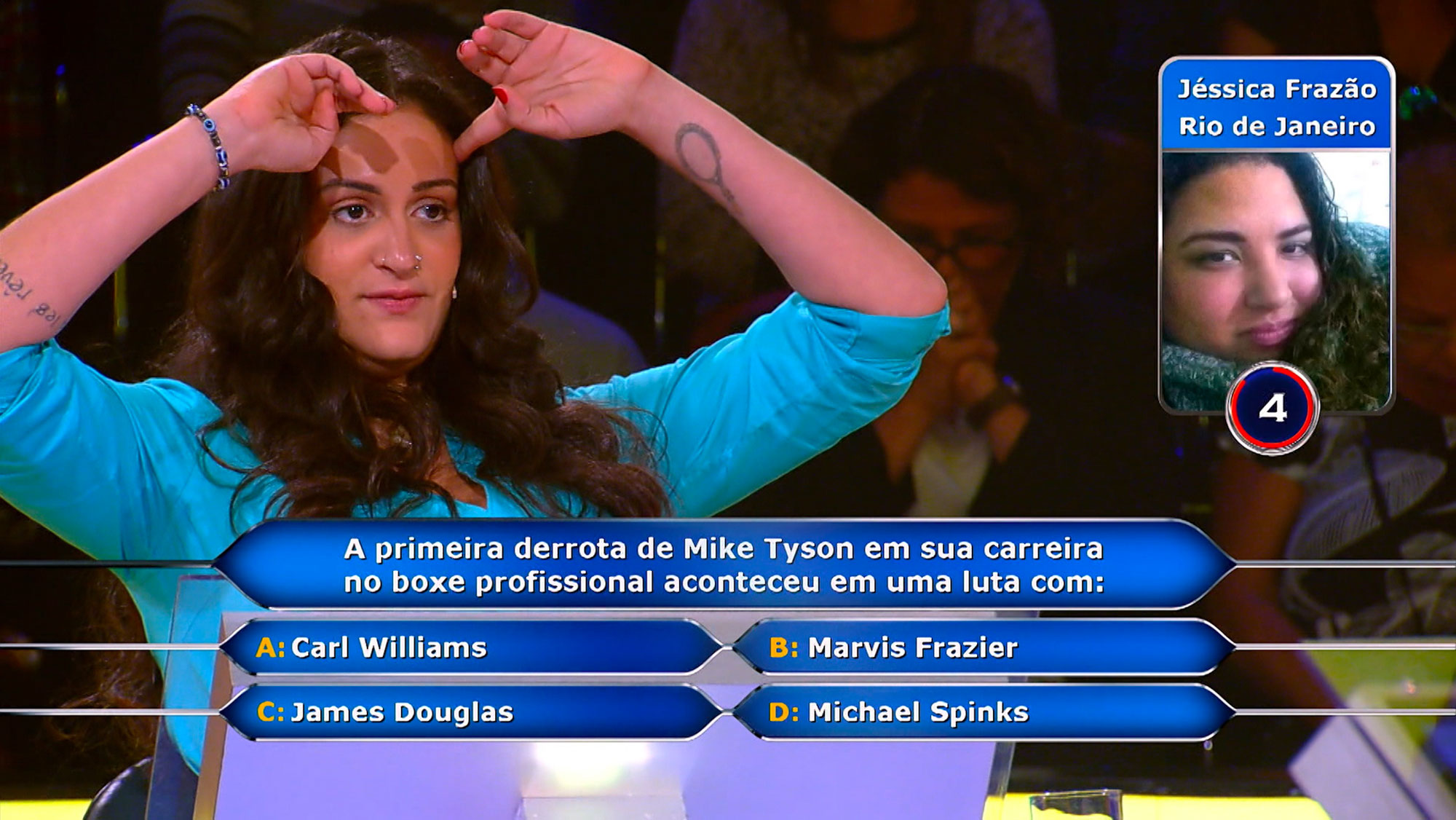

With no better options, Fraza˜o set about sending scores of emails to anyone who might help. The results weren’t encouraging—save one. Her plea had somehow reached the producers of Brazil’s version of Who Wants to be Millionaire.

Fraza˜o was booked on a taping that June. All she had to do was win big. “I was like, that’s it,” she says. “I’m going to Stanford.”

Her daughter had been accepted to Stanford, but she wasn’t going. The revelation stopped one guest, a stranger, in his tracks.

Fraza˜o had a history of performing well when her schooling was on the line. She’d realized early on that education was the key to a better life. But that path seemed blocked when she started high school. Her memories of the first week consist of students screaming and shouting, and of general chaos. “I can’t stay here,” she recalls thinking.

So she came up with a bold response: She’d drop out of school, cram for a year and take the admission tests to the city’s elite high schools. It was crazy, she says, but her mom backed her. Fraza˜o aced the tests.

Her success propelled her into a more affluent world, one where she felt like an outsider in her sister’s hand-me-downs. But she excelled again, winning a full ride to the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. There she studied industrial design and fell deep into the world of combat robotics, where teams create fighting machines that face off in no-holds-barred competitions.

She loved the pressure, the competition and the collision of hard-learned theory with hard-crunching reality. It was a similar mixing of worlds—the blend of technical knowledge with human-centered design—that drew her to Stanford.

She just needed a movie-like moment of magic to get there.

But under the stage lights came a knockout blow. Fraza˜o guessed wrong on the 100,000-real question and left with half that amount—the equivalent of about $10,000—and her hopes in tatters.

Soon afterward, Fraza˜o’s mother, Suzete, was invited to a party honoring the founder of the clinic where she had worked. Not wanting to wallow at home, Luciana asked to be her plus-one.

And so it was that on June 14, 2019, Fraza˜o was sitting alone at a corner table at a soiree where she knew almost no one. Her mom was doing her social duty and sharing the disappointing news: Her daughter had been accepted to Stanford, but she wasn’t going.

GREAT PARTY: Frazão and her mother, Suzete, left, met Carlos Brito at a reception honoring Brito's father in 2019. (Photo: Courtesy Luciana Frazão)

GREAT PARTY: Frazão and her mother, Suzete, left, met Carlos Brito at a reception honoring Brito's father in 2019. (Photo: Courtesy Luciana Frazão)

The revelation stopped one guest, a stranger, in his tracks. Carlos Brito, who had flown in from the United States for the event honoring his dad, wanted to know more about Suzete Fraza˜o’s daughter. Then he wanted to talk to Luciana. He found her still in the corner.

Brito had made his own unlikely journey to the Farm. In the late ’80s, he’d been accepted to the Graduate School of Business but had no way of paying for it. In an era of high inflation and depreciated currency in Brazil, the expense was well beyond reach for his middle-class family.

But he knew of an investment bank that gave loans to employees pursuing MBAs. Brito used connections to get an interview with its main partner, Jorge Paulo Lemann, who gave him a one-hour meeting. Ultimately, Lemann’s company couldn’t offer Brito a loan, because he wasn’t a bank employee. But Lemann would personally pay for Brito’s first year at Stanford in exchange for three things: regular updates on his progress, a promise to talk to his bank before accepting any job, and a commitment to helping others in a similar position.

THE BENEFACTOR: Brito, MBA ’89, continued a chain of giving from which he, too, had benefited. (Photo: Saul Bromberger/Stanford Graduate School of Business)

THE BENEFACTOR: Brito, MBA ’89, continued a chain of giving from which he, too, had benefited. (Photo: Saul Bromberger/Stanford Graduate School of Business)

More than 30 years later, Brito, MBA ’89, is chief executive officer of Anheuser Busch-InBev, the world’s largest beer producer. The sprawling beverage empire grew out of one of Lemann’s companies’ 1990s acquisition of a pair of Brazilian breweries. Despite far more lucrative offers at the time, Brito had gone to work for his patron after finishing business school, and never left.

Brito had long since made good on his commitment to help others by regularly funding scholarships, many for GSB students. But those contributions were through a foundation with a formal process. Now, at a party, he was about to make a move even more unorthodox than Lemann’s was a generation earlier.

Fraza˜o had cleared so many hurdles. Brito was going to help her over the next. “I spoke to her a little bit, and said, ‘You know what, I’m going to pay for your school. Somebody did that with me. I’m going to do it with you,’ ” he recalls.

Fraza˜o was in disbelief. A few minutes earlier she’d had no idea Brito existed. The next day she emailed to ask if she’d heard him correctly. She had.

Two years later, Fraza˜o is on the cusp of graduating with a master’s in mechanical engineering. Much of her research on campus has been on using robotics to keep elderly people from falling, an idea inspired by her grandmother, who died shortly after Fraza˜o moved to California.

PAYING IT FORWARD: Brito and his wife, Belinda, with Frazão. (Photo: Courtesy Luciana Frazão)

PAYING IT FORWARD: Brito and his wife, Belinda, with Frazão. (Photo: Courtesy Luciana Frazão)

In April, to Brito’s delight, Fraza˜o started as a global research manager at Z-Tech, an Anheuser-Busch InBev unit focused on enabling small and medium-size companies to grow through their use of technology.

Her long-term goal is to return to Brazil and use social entrepreneurship to help mothers like her own who are financially crushed by divorce. But she’s not waiting until then to pay her good fortune forward.

Early this year, she was contacted by Maria Luisa Viera Parada, a young Brazilian who’d been accepted to Princeton as an undergrad. Even after taking a gap year to work multiple jobs, Parada had been unable to save enough money to attend.

She called Fraza˜o seeking advice. Instead, she got an instant champion. The two women talked for a while, and Fraza˜o told Parada about the links connecting Lemann to Brito to herself. And now to Parada. She was going to do everything she could to ensure that Parada went to Princeton.

Fraza˜o began spreading Parada’s story among her network of Brazilian expats. Many of them donated to a GoFundMe that Fraza˜o had encouraged Parada to set up. Others gave advice and encouragement. One helped Parada write to Princeton to request more financial aid. And with her new job, Fraza˜o herself promised to cover whatever other costs came up, from plane tickets to laptop expenses to incidentals.

“I was shocked,” says Parada. “You never think you’re going to wake up and be like, ‘I’m going to have a call, and this call is going to change my whole life.’ ”

For Fraza˜o, it was meant to be. In Parada’s story, she heard her own. She wanted to make sure it had a similar ending. “I just felt that this was the moment for me to give back.”

Sam Scott is a senior writer at Stanford. Email him at sscott3@stanford.edu.