Half a century after he first arrived on the Farm, Keni Washington admits he chose Stanford mostly because of the weather. A military school graduate from Indiana, he had been accepted at Brown but came west for the sunshine. He was one of only 10 African Americans in the 1964 freshman class. He had not the vaguest premonition of the storms that awaited.

His roommate in Wilbur-Trancos dorm was Gary Petersmeyer, '68, who went on to be a three-year starter for the basketball team. Petersmeyer was pursued by a few fraternities on campus, including Sigma Chi, and Washington got to know some of its members. One day, recalls Washington, one of them said, "Hey, why don't you come up to the house, too? . . . I don't think they had any expectation as to what would happen. They didn't let on if they did."

What happened was this: Washington, '68, was invited to pledge Sigma Chi, a national fraternity founded in 1855 that had never had a Black member. The move ignited a confrontation between the Stanford Sigma Chi chapter and its 110-year-old parent, made national headlines and thrust Washington into the role of pathbreaker. Momentarily, a frat house on the Farm became one of the country's hot spots in the civil rights movement.

Sigma Chi's rules prohibited membership for anyone "likely to be considered personally unacceptable as a brother by any chapter or any member anywhere." That was the kind of sweeping provision used as a replacement for "whites only" or other blatantly discriminatory language. At the height of the controversy over Washington, Sigma Chi's grand consul, Harry V. Wade, predicted the fraternity would never have an African American member.

The Stanford chapter wasn't spoiling for a fight, but its members chafed at the notion that race should be a factor in membership considerations. A letter sent to chapter alums in late 1964 warned that the house was in crisis because it was "not free to pledge Negroes." In February 1965 the chapter sent a letter to Sigma Chi officials saying it intended to rush prospective members on a nondiscriminatory basis.

When pledge bids were given out in March 1965, one went to Washington, who accepted on April 3. On April 10, word arrived that Sigma Chi's national executive committee had suspended the Stanford chapter as of April 2, allegedly for chronic flouting of rituals and traditions.

Stanford's Sigma Chi members saw a ruse, a trumped-up attack on the chapter's overall decorum, to block Washington's admittance. Pat Forster, '65, a chapter member, says it was assumed that Washington's recruitment had leaked to the Sigma Chi establishment and "they had to figure out some kind of excuse."

On April 13, the Stanford Daily reported the suspension as its lead story, quoting chapter president Gary Kerns, '65, who summed up the house's position: "We have pledged a Negro. . . . We will not give up the pledge to stay in the national but we intend to try to convince the national organization that we should stay affiliated."

A torrent of reaction followed. U.S. senator and Sigma Chi alumnus Lee Metcalf, '36, a Montana Democrat, pushed for a federal ruling on whether discrimination by fraternities violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The determination was crucial because government funding could be withheld from a school that allowed such a practice, potentially endangering millions of dollars in research grants. Stanford already had explicit nondiscrimination policies in place, and President J.E. Wallace Sterling's administration had jumped to the defense of the suspended chapter.

Repercussions from the Stanford uproar reached other campuses quickly. The University of Colorado regents insisted that their school's Sigma Chi chapter provide evidence that the action against the Stanford house was not connected to pledging the African American student. Unconvinced by the response, the university put the chapter on probation. Near the end of April, Stanford sent a letter to more than 130 colleges and universities warning of the potential link between fraternity behavior and loss of federal aid.

Press accounts pushed the matter onto a national stage. The New York Times reported the story under the headline "Stanford Fraternity That Pledged Negro Fights Suspension." Look magazine published a five-page story in its July 27 issue. In an array of photos, Washington appeared composed and resolute. In one, he smiled genially while on a double date: Fraternity brother and basketball co-captain Kent Hinckley, '65, escorted Sharon Smull, '67; Washington went with Charlotte Strother, '68, another African American freshman and his future wife.

But the story noted that Washington's "cool, relaxed manner covers a tautness"—in retrospect, both an insight and an understatement. Although Washington had shed any naïveté about race relations well before college, the distress and disruption of the Sigma Chi fallout were undermining the rest of his Stanford experience.

At Howe Military Academy in northern Indiana, Washington and a classmate had been the school's first African American graduates. Washington had been cadet captain and company commander, captain of the basketball team and a state speech champion. Outside of Howe, he'd had to throw fists along with rebuttals, particularly as a response to the N-word. "If they're going to call you that name," he decided, "they need to know where it stops."

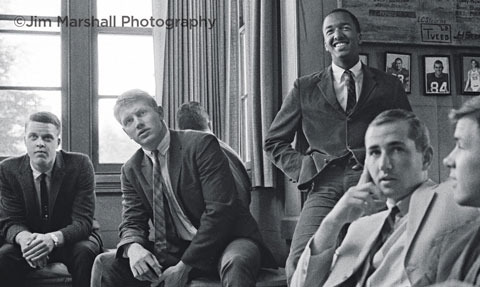

CONSPICUOUS: Stanford's student body was overwhelmingly white in the mid-60s, but the University was beginning efforts to diversity. (Photo: Copyright Jim Marshall Photography)

CONSPICUOUS: Stanford's student body was overwhelmingly white in the mid-60s, but the University was beginning efforts to diversity. (Photo: Copyright Jim Marshall Photography)

One experience exposed him to deeper divides: When his mother took him to Houston for the national speech finals, "There was not one restaurant we could eat in. There was not one hotel we could stay in. So we stayed with some extended family friends."

At Stanford, he suddenly faced the strain of becoming a symbol for racial justice. It was a fight Washington accepted, even though he hadn't sought it. He recognized that the stakes were much bigger than the effect on him personally. But he wasn't impervious. Almost 50 years later, he's still conscious of the sting. "I would imagine," says Washington, now 68, "that no sane person enjoys being rejected for reasons that have nothing to do with your achievements and capabilities in life. That's what racism does. It questions your humanity, your basic humanity."

The integration of fraternities "wasn't a burning issue for me," he explains. "But it was also something I knew was important to follow through with and to be a part of, because it was just one more avenue of divesting racism in the country."

That left him at the center of the Sigma Chi tempest at the same time he was acting on strong antiwar feelings about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. As with any memories that are five decades old, some details are hazy. How much disquiet he felt about one thing versus another isn't always clear. But he remembers that "the capper" for him was a visit to the Stanford Sigma Chi chapter by Sen. Metcalf. Washington eagerly approached him with questions concerning recent news about Vietnam.

IN THE MIX: Washington at an antiwar protest on campus. (Photo: Chuck Painter / Stanford News Service)

IN THE MIX: Washington at an antiwar protest on campus. (Photo: Chuck Painter / Stanford News Service)

"He was totally oblivious about it," says Washington, his resentment reigniting. "And I said to myself, 'This is one of the top 100 people in the country, who has my life and the life of my generation in his hands. He doesn't give a shit enough to understand and to be on top of this life-and-death issue for my generation. Why am I supposed to crave being part of an organization that reveres him?'"

Ultimately, the incident probably augured more about Washington's overall future at Stanford than at the fraternity. Events involving his antiwar principles and his role with the Black Student Union would eventually eclipse the fraternity matter in his undergraduate life. But first the Sigma Chi conflict blazed. The Stanford chapter, vigorously backed by the University, had carried the fight to an appeal hearing on the suspension during Sigma Chi's national convention in June.

Washington with Marguerite Hoxie Sullivan, '68, MA '71, as a panelist at his class's 45-year reunion last October. (Photo: Patty Ponciano)

Washington with Marguerite Hoxie Sullivan, '68, MA '71, as a panelist at his class's 45-year reunion last October. (Photo: Patty Ponciano)

Forster was among the contingent in Denver and recalls the media throng's futile jockeying to get inside the hearing. Also doomed was Stanford's case: The suspension was upheld.

Just before that, however, U.S. Commissioner of Education Francis Keppel, citing Stanford's Sigma Chi showdown as a catalyst, had issued his opinion that the language of the Civil Rights Act required schools to ensure fraternities were discrimination-free or risk a cutoff of all government funding. Fraternity and sorority civil rights controversies had been making headlines at least since the end of World War II; now the context was each chapter's individual obligation to federal law.

At the Stanford frat, seniors graduated, leadership turned over, and Forster and others could stay involved in the Sigma Chi fray only for a limited time. But Forster was among those who remained informed, learning of the next big development in April 1966 while in England on a Marshall Scholarship. That was when the national Sigma Chi officials reinstated the Stanford house under strict probation. It so happened—as the chapter pointed out—that the decision coincided with Washington becoming academically ineligible for membership.

Today, alums who knew Washington but didn't follow all the Sigma Chi details are confounded when told his grades became an issue. They remember him as intellectually gifted, with a variety of talents. When Forster heard the news in '66, he was dismayed, more for Washington personally than for any other reason. He worried "that we might have taken advantage of him without meaning to; that it took too much of a toll on him."

Indeed, Washington had been slipping toward an estrangement from Stanford. He sometimes felt adrift while trying to cope with all his challenges, including in the classroom. He remembers a faculty adviser who was a nice person but who provided no specific guidance. And Washington didn't push for better help: "I didn't know how much I needed it."

More meaningfully, he was increasingly angered by what he considered a "veneer" of progressivism throughout Stanford. One embittering experience involved his inquiries about off-campus housing. He believes University administrators denied him a complete list of choices, which made them seemingly complicit with landlords who discriminated against Blacks. Stanford attempted to corroborate some details, but couldn't reconcile Washington's memories with those of someone else he says was privy to the matter. Whatever happened, it deeply tainted his attitude toward the University.

As Washington became less central to the ongoing rift with Sigma Chi, he let the fraternity turmoil fade into the background. "I never officially left," he notes. He remembers living at the fraternity for a while, then leaving and dropping away from any participation in the chapter's activities. But for the Stanford chapter—not to mention Sigma Chi and fraternities nationally—the principles of open membership remained on the line.

The landmark moment had been Keppel's assertion of federal jurisdiction, backed up by the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Nothing else was really unique to the Sigma Chi situation, in either the nature of the controversy or Stanford history. The New York Times reported that Stanford had 23 fraternities—seven with no African Americans—and that two chapters, Alpha Tau Omega in 1961 and Sigma Nu in 1962, had already cut ties with their national organizations to expunge biased membership rules.

Even so, the intensity of the dispute surrounding Washington generated a power all its own. Beyond the ramifications for other colleges and universities, the episode revealed the seamier side of a so-called fraternal order. Not only had Sigma Chi remained one of the most overtly exclusionary fraternities in the country, it also was belligerently represented by Wade, whose correspondence with the Stanford chapter was filled with pejorative flourishes. Time magazine quoted a letter in which Wade explained that he might personally support "a high-class Chinese or Japanese boy" but couldn't justify it for Sigma Chi at Stanford because of the expected objections from West Coast chapters.

In November 1966, as Sigma Chi's leadership continued to deny that its practices were discriminatory, the Stanford chapter decided to separate from the national fraternity and become an independent fraternity house. There was nothing convenient or trivial about the decision. Fraternities in those years played a much larger role in college culture, in part because membership in such groups had more social appeal and prestige. Leaving the national fraternity upended the chapter's most basic bond with older alums and in some ways shattered its identity.

But history caught up. In 1971, the national organization revised its rules, eliminating membership barriers for Sigma Chi chapters, informed in part by the Stanford case. Three years later, the Stanford chapter reaffiliated with the national fraternity.

Gary Kerns, who acknowledges that he and others at the Stanford chapter had a rebellious streak, says local autonomy was one of the subplots to the Washington saga. Support for Stanford was even voiced by Southern chapters, Kerns recalls, because they were such fierce advocates of states' rights. It all added up to an important impetus for change, as recognized within today's Sigma Chi.

I would imagine that no sane person enjoys being rejected for reasons that have nothing to do with your achievements and capabilities in life.

Douglas Carlson, a past grand consul and past grand historian for the fraternity, says the actions of the Stanford chapter proved "fortunate" for Sigma Chi, sparking "more intense awareness and debates" on an issue that had burdened the organization since the late 1940s. "I would say those students and Ken Washington helped cause the fraternity to change years sooner than it would have otherwise," he says.

Though no definitive records are available to confirm the claim, Carlson says Washington likely was the first African American pledged by any chapter of Sigma Chi.

To this day, Washington searches for perspective on everything that happened. African Americans constituted less than 1 percent of his freshman class. In a climate stirred by the convergence of civil rights, antiwar activism and his own personal turmoil, he was subjected to a whirlpool during his three years on campus. And, yes, it was three years, not four.

Washington spent his junior year at Southern Colorado State, he says, because he was temporarily barred from Stanford for his participation in an antiwar protest—a three-day occupation of President Sterling's office in May 1966. He says he was subsequently suspended for a year, notified by letter as he recalls it from Dean of Students H. Donald Winbigler. He returned for his senior year.

Washington remains outspoken. Before the presidential election in 2012, the Stanford Daily published an open letter from Washington to Republican candidate Mitt Romney. Prompted by media accounts describing Romney's participation in a counterprotest to the sit-in at Sterling's office, Washington excoriated him for supporting the Vietnam War without having served in the military.

That zeal for the causes of the time put Washington in the thick of an extraordinary chain of events in April 1968 after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Washington, co-chair with Charles Countee, '67, of the Black Student Union, was among campus and community activists challenging Stanford to do more for minorities. Four days after King's death, the University held a colloquium on racism in Memorial Auditorium. Early in the session, members of the BSU, including Washington, peacefully commandeered the podium from then-provost Richard Lyman in an action remembered as "the taking of the mike."

The group issued 10 demands in matters including admissions, faculty hiring and academic programs. Precarious negotiations followed, ultimately considered successful. In his 2009 memoir Stanford in Turmoil, Lyman notes more than once that Washington and Countee were crucial in keeping the talks from dissolving into an impasse. His book recounts a delicate moment when Washington called for a short time-out at a troubled juncture. When the conversation resumed, so did progress.

SEEN AND HEARD: An accomplished musician, Washington played in a jazz ensemble (Photo: Copyright Jim Marshall Photography)

SEEN AND HEARD: An accomplished musician, Washington played in a jazz ensemble (Photo: Copyright Jim Marshall Photography)

Washington's capacities for organizing people and formulating strategy somehow balanced a tenacious style with nonviolence. Internally, though, his anger was more consuming. Alienated by America's racial tensions, he and Strother, whom he had married a year earlier, were talking about moving to Europe. Conflicted and upset about his time at Stanford, Washington didn't complete his degree. "It was my decision to leave school before graduation," he says.

Amid everything else, Washington, an accomplished tenor sax player who also was a deejay for KZSU, had been able to establish a prospective career as a musician. His Stanford jazz group, Smoke, attracted attention for its combination of white and African American musicians, as well as for its avant-garde sound. Members included Fred Berry, Gr '69, now director of the Stanford Jazz Orchestra and a lecturer in the music department. Signed by a German record label, the group cut an album, and Washington and Strother focused on saving money to go overseas.

Then tragedy intervened. Strother was killed in an automobile accident that also left their toddler son, Kenneth Jr., with a skull fracture and other injuries. Washington, who wasn't with them, was beset by guilt, thinking he might have avoided the crash had he been driving. In shock, it took him years to regain some emotional equilibrium.

"My whole life trajectory . . . it changed overnight," he says. "Within a few months I was actually out of music. Because to be a successful musician, and unless you're just doing it as a hobby, you've got to travel." And that was out of the question for Washington as a single parent.

Washington and Strother met on the Farm and latter married, before tragedy struck. (Photo: Copyright Jim Marshall Photography).Over the next 20 years in the Bay Area, he forged a career in a series of businesses, including telecommunications and property management. In the late 1980s, a visit to Indianapolis prompted him to relocate there. He left the business world and again dedicated himself to music. He played professionally with a quintet, wrote for ensembles and made CDs. As a performer, he spelled his first name Keni and decided to keep it that way, after a lifetime as Ken.

Washington and Strother met on the Farm and latter married, before tragedy struck. (Photo: Copyright Jim Marshall Photography).Over the next 20 years in the Bay Area, he forged a career in a series of businesses, including telecommunications and property management. In the late 1980s, a visit to Indianapolis prompted him to relocate there. He left the business world and again dedicated himself to music. He played professionally with a quintet, wrote for ensembles and made CDs. As a performer, he spelled his first name Keni and decided to keep it that way, after a lifetime as Ken.

In 2007, his social conscience, still loud and persuasive in his head, drove him back to business. Furious over what he labels a generational and political failure to adequately battle global warming, he founded Earth-Solar Technologies, a company focused on renewable energy products. Says Washington, "I want to see us do as much damage to the fossil-fuel world order as possible."

Now a grandfather of three, Washington is married to Katharina Dulckeit, a professor of philosophy at Butler University.

In recent months, responding to Stanford's numerous questions about his days at Stanford, he has been trying to sort through a maze of details and emotions—"resurrecting concepts and memories that I haven't thought about in 40-plus years!" For many of those years, Washington's relationship with Stanford was at best casual. Parts of his experience remain vivid; other parts, such as the precise details of his antiwar suspension, he put aside without any desire to check his official records. The indignation he felt during his undergraduate days has never fully dissipated.

In 2002, he was invited back to speak on a panel as part of a two-week tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. He has been back twice more, including in October as a class speaker for his 45th reunion. Through those moments, when blunt recountings of the 1960s have been welcomed, he has found some new footing with the way his history and Stanford's are intertwined. In many minds, as a 2002 Stanford Report story observed, Washington and other former activists have acquired an image akin to folk heroes.

How much of what happened at Stanford echoes for him? How much did it shape him?

"I think that's a very good question. Maybe in big ways," he says. "I mean, no one's put the question to me like that before. And maybe since you asked it like that, it is the case that being at Stanford exposed me to coherent thinking about solving conflict without violence."

And Sigma Chi?

"I just don't know how important it is," he said in October, around the time news reports described alleged discrimination at a Southern sorority. "But in recent years . . . I've come to appreciate it more than I ever did before."

He speaks glowingly, for instance, of Frank Olrich, '65, MA '66, the Stanford chapter president who was unflinching in the earliest stages of the Sigma Chi confrontation. Olrich, who died in 1999, was unforgettable, Washington says, in both his kindness and his sense of justice.

I've come to respect and honor those guys because they are the ones who really sacrificed that organizational brotherhood and fellowship.

"I'll tell you the part that I appreciate," he adds. "It's the sacrifice by the white Sigma Chis, who wanted so much to be part of their national fraternity. They in fact sacrificed being embraced by the national fraternity on behalf of integrating. And I've come to respect and honor those guys because they are the ones who really sacrificed that organizational brotherhood and fellowship."

"Those guys" continue to express pride in what they did. But they also say they didn't do it as a crusade and weren't seeking the country's attention. Larry Hough, '66, one of the chapter presidents who took a turn wrangling with Sigma Chi, says Washington was simply a guy whom everybody wanted. "I can't think of a fraternity on campus that wouldn't have welcomed Kenny Washington."

Maybe the Stanford chapter was full of upstarts, says Kerns, but there was no intent to embarrass Sigma Chi or make a national statement. "We were just kids who thought race was a non-factor," he says. That's what brotherhood and fellowship meant. That's what a fraternity meant.

Rush Moody, '14, the recent president of Stanford's Sigma Chi chapter, doesn't know Keni Washington. But he knows of him.

"New pledges have to learn the history of the chapter," he says, "and what happened with Ken Washington is a point of pride: Don't be afraid to do what's right."

Mike Antonucci is a senior writer at Stanford.