Elizabeth Jameson wants you to look at her. Really look at her. See her high-tech wheelchair, custom fit to her slender body. See her immobile legs and arms, her carefully folded hands. See her shiny blond hair and her penetrating hazel eyes.

People often look away from those with disabilities, says Jameson, in the same way they avoid talking about illness. But it is time to change that.

Jameson, ’73, who has multiple sclerosis, uses magnetic resonance imaging of her brain to create art that is intended to provoke conversation about illness and disability as part of the human experience.

Artist Elizabeth Jameson (Photo: Cheryl Bowlan)The arresting pieces, with titles such as Emerging, Celebration and Conversations with Myself, have appeared in publications from Scientific American to Fast Company and at galleries and institutions across the country, including Harvard, Yale and the National Institutes of Health.

Artist Elizabeth Jameson (Photo: Cheryl Bowlan)The arresting pieces, with titles such as Emerging, Celebration and Conversations with Myself, have appeared in publications from Scientific American to Fast Company and at galleries and institutions across the country, including Harvard, Yale and the National Institutes of Health.

“We need to change the narrative of illness and aging and disability,” says Jameson. “I combine science and art to get people thinking and talking about life with disease, because we are all going to be there one day.”

The Art of Service

As a child, Jameson says, she admired the nuns who taught her in parochial school, and she considered becoming a nun so she could devote her life to helping people.

“Then, at Stanford, I found out women could be lawyers,” she says. “It was the ’70s and a great time to impact social change. It was doing some of the same things as a nun, working to make the world a better place, but being a lawyer sounded better.”

‘I could make a difference, and that is what I wanted to do in my life.’

Jameson majored in history at Stanford, then went straight to law school at UC-Berkeley. After clerking for a federal district court judge for two years, she landed her dream job at the nonprofit Youth Law Center in San Francisco. As a lawyer representing incarcerated children, Jameson took on cases across the country in which children had been put into solitary confinement, injected with drugs to control their behavior and subjected to abuses she says “you wouldn’t even imagine — it was like the 14th century.”

The work was both depressing and energizing, Jameson says. “I could make a difference, and that is what I wanted to do in my life.”

CELEBRATION: Jameson hoped to lift a friend’s spirits with this Solarplate etching of blood vessels that caught her eye on his brain angiogram.

CELEBRATION: Jameson hoped to lift a friend’s spirits with this Solarplate etching of blood vessels that caught her eye on his brain angiogram.

A Life-changing Day at the Park

In 1991, Jameson had a busy career and a young family. She was at the park pushing her two sons on the swings one day when she abruptly lost the ability to speak. At first doctors suspected a brain tumor or a stroke. More tests revealed she had multiple sclerosis, a progressive disease of the central nervous system that disrupts the flow of information in the brain and between the brain and the body.

Strange symptoms came and went; as time passed, more of them stayed. By 1993, the civil rights attorney struggled to stand or walk. The strength of her voice gradually diminished, and she experienced episodes of aphasia, which made it difficult for her to speak and write. By the mid-1990s, practicing law was no longer possible. Jameson retired with a broken heart.

‘I had so many MRIs. They were black, ugly, scary images I had refused to look at, but it was as if they were tattooed on my forehead. I couldn’t wash them off.’

“When I stopped practicing law,” she says, “I had to find out what I was going to do with my life. With aphasia, I could not say the names of my kids, but I could still cite Supreme Court cases. I had defined myself as a public interest lawyer.”

Grieving the loss of her life’s work, she let a friend talk her into attending a community art class. It was the first time she’d held a paintbrush, and she fell in love with the smell and feel of paint. She began painting “obsessively,” she says, but painting still lifes didn’t reflect her new identity as someone living with illness. Nor did it feed her desire to serve a greater good. Her mind kept returning to the stark black-and-white images of her degenerating brain that were accumulating in a corner back at home.

VALENTINE: Color highlights heart-shaped structures in this coronal view of Jameson’s brain stem, cerebellum and lateral ventricles.

VALENTINE: Color highlights heart-shaped structures in this coronal view of Jameson’s brain stem, cerebellum and lateral ventricles.

“I had so many MRIs,” she says. “They were black, ugly, scary images I had refused to look at, but it was as if they were tattooed on my forehead. I couldn’t wash them off.

“I decided to really examine what the MRIs meant to me and what they mean to all people who undergo medical testing on a daily basis. And so I went to work.”

Living Color

Jameson began painting in oil and acrylic and working with silk fabrics and dyes. Then a printmaker introduced her to Solarplate etching, which employs a light-sensitized, steel-backed polymer material used by artists as an alternative to traditional printing techniques.

Jameson chooses the section of a black-and-white scan she wants to feature and places it on the Solarplate. When sunlight hits the plate, it creates a relief image that can then be enhanced with ink. The final image is printed on paper.

“Elizabeth’s artwork opens people’s minds. As people get to know her work, I think their understanding of illness and disability shifts.”

“It’s all in the wiping down of the intensity of the printing inks,” she says. “Sometimes the resulting images work, but as you can imagine, many do not work out. It can take several attempts, even weeks, to get an etching that works in terms of color, contrast and intensity.”

As her disease progressed, her process evolved. Jameson turned to studio assistants for help and expanded into other media, including digital collage and photography.

Elizabeth’s artwork opens people’s minds. As people get to know her work, I think their understanding of illness and disability shifts,” says writer-artist Catherine Monahon, one of Jameson’s collaborators and studio assistants.

CIRCUITBREAKER NARRATIVE: Jameson created this tapestry to depict the “blown-apart” pieces of her life.

CIRCUITBREAKER NARRATIVE: Jameson created this tapestry to depict the “blown-apart” pieces of her life.

Circuitbreaker Narrative (right), a cobalt blue textile collage, juxtaposes square pieces of MRI scans with scraps of medical reports and pieces of a painted self-portrait. “It describes trying to put the pieces of my life back together, which were blown apart by the tsunami,” Jameson said in her 2017 TEDxStanford talk.

Conversations with Myself is a large horizontal work constructed from two MRIs positioned so they face each other. Medical notes appear in soft white print behind colorfully highlighted side views of Jameson’s brain.

“Elizabeth gets fan mail from people all over the world,” says Monahon. “People living with brain disease, affected by MS or cancer or bipolar disorder, neuroscience students, people who work at pharma companies, people whose mother has MS, caregivers, physicians. Her work makes a difference because it opens up conversations about issues that are typically so private, so taboo and yet so pervasive in our society.”

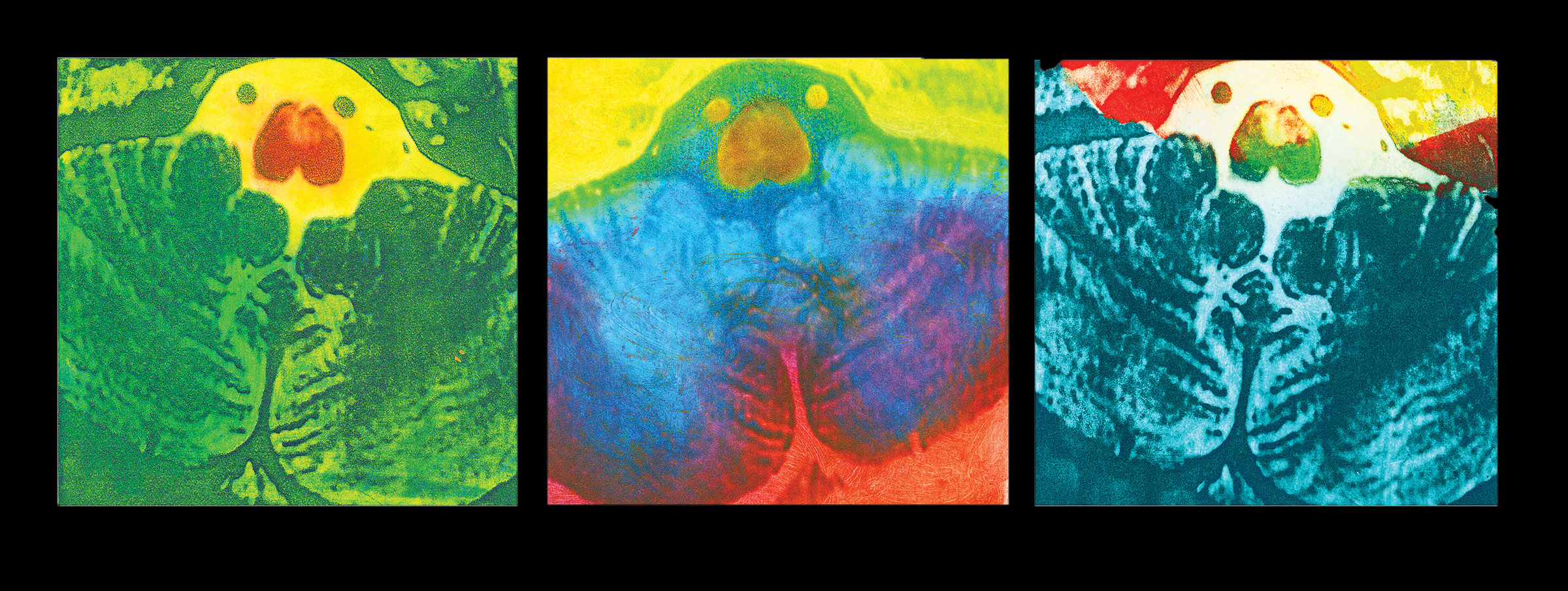

Another series, Bird Brain (below), appears to show a bird facing the viewer, its wings folded in front of it. In fact, the image is an axial view of the lower brain stem and cerebellum, the area that controls autonomic functions such as breathing and heart rate. (Jameson jokes that her family often referred to her as birdbrained, and now they have proof.)

“It is inspiring both from a philosophical and certainly from an artistic point of view when an artist turns their lens or brush or scanner inward,” says UCSF neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley, who directs Neuroscape, a research center focusing on technology and the brain. Gazzaley and Jameson worked together on a 2013 PBS special that featured Jameson’s art.

BIRD BRAIN: A familiar-looking visage hiding in an MRI inspired the artist to create this series.

BIRD BRAIN: A familiar-looking visage hiding in an MRI inspired the artist to create this series.

Space for Connection

If one part of Jameson’s mission as a public interest artist is helping healthy people understand the universality of illness and disability, another part is empowering people living with disease to share their feelings and connect with one another.

The Waiting Room Project is a multimedia installation for building community in clinical spaces, where patients often experience isolation and anxiety while waiting for treatment or diagnosis. Patients and their family members and caregivers want to connect with others in these moments, Jameson says; she knows because she has asked them.

On display in clinics from UCSF to the University of Miami, the installation consists of 3-by-4-inch conversation cards, writing implements and a monitor that displays a slideshow of completed cards.

Each conversation card bears a prompt such as “I wish my health provider knew . . .” or “One thing I wish the world knew about my illness is . . .” or “Today I am here because. . . .”

CONVERSATIONS WITH MYSELF: This Solarplate etching and pastel on paper is part of Jameson’s Brain Diaries series.

CONVERSATIONS WITH MYSELF: This Solarplate etching and pastel on paper is part of Jameson’s Brain Diaries series.

Portraits of people of varying ages and ethnicities living with MS line the walls of the installation rooms, inviting visitors to look closely and contribute their own stories. Responses have been prolific, vulnerable, revealing:

“I want to take my medical care into my own hands.” “I’m 34 and afraid my MS is progressing. Will I be able to run when I am 50?” “I’m smart enough to hear all the details. Tell me.” “I just wanna be OK.”

“The point of interacting in the waiting room isn’t to become best friends with the person sitting next to you,” says Jameson. “These moments of connection are about acknowledging illness in all its forms; creating new, positive experiences; and offering an alternative to the awkward silences in the clinical setting. There is a sense of pride, or togetherness, when we honor our own thoughts and feelings. And to share these thoughts and feelings in such a vulnerable place as the clinic waiting room is empowering for all.”

Jameson hopes the project will become a model for other waiting rooms in clinics where those facing chronic illness are treated. For now, she intends to do everything she can to keep the conversations going.

“My neurologist thinks I won’t lose my voice completely, but there is no way of knowing,” says Jameson. “I have so much to say, so I have to talk now, while I still can.”

Melinda Sacks, ’74, is a senior writer at Stanford.