Americans take the identities of their two political parties for granted. But it is worthwhile to ask: Why does the party that supports higher taxation and more regulation of the domestic economy also support freer international trade and immigration? Why does the party that favors less regulation of markets for labor and firearms also advocate more regulation of abortion and sexuality?

These odd collections of policy positions are bundled together by the two parties not because of intellectual coherence, but because of the incentives created by American political institutions and political geography. In order to understand the rise of political polarization since the 1970s, we must understand how political competition in the United States came to be organized as a battle between the interests of cities and inner suburbs, and those of exurban and rural voters.

The correlation between population density and Democratic voting emerged in the manufacturing states during the New Deal, when the Democrats mobilized urban workers around a progressive economic agenda. In order to gain legislative support for this agenda, urban Democrats made an alliance with rural Southern segregationists. This alliance eventually frayed, however, as the Democratic members of Congress embraced the civil rights movement in response to the interests of black working-class constituents in Northern cities. Thus began the slow extinction of rural white Southern Democrats and the spread of urban-rural polarization from the North to the South.

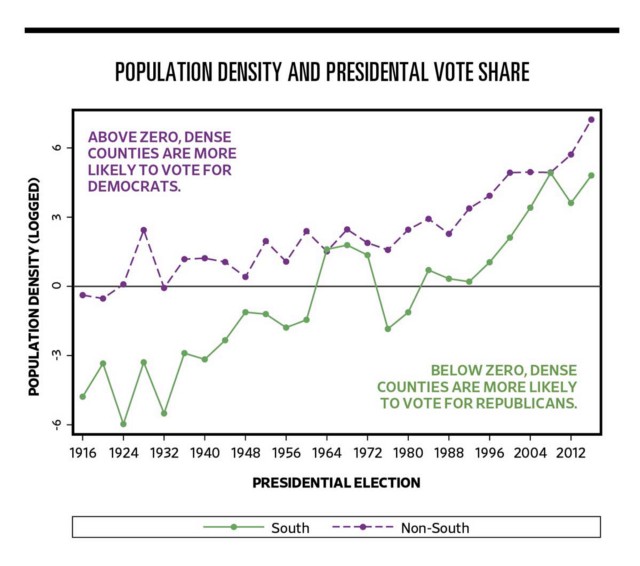

This graph uses county-level data to assess the relationship between population density and Democratic voting. It reveals that outside the South, the relationship between population density and Democratic voting emerged first in the New Deal era in the 1930s, and has slowly climbed ever since, with a steeper increase beginning in the 1980s. In the South, the relationship between population density and Democratic voting was reversed in the era of the Southern Democrats. In the contemporary era, the relationship between density and Democratic voting in the South has come to resemble that of the North. (Graph: Courtesy Jonathan Rodden)

This graph uses county-level data to assess the relationship between population density and Democratic voting. It reveals that outside the South, the relationship between population density and Democratic voting emerged first in the New Deal era in the 1930s, and has slowly climbed ever since, with a steeper increase beginning in the 1980s. In the South, the relationship between population density and Democratic voting was reversed in the era of the Southern Democrats. In the contemporary era, the relationship between density and Democratic voting in the South has come to resemble that of the North. (Graph: Courtesy Jonathan Rodden)

Manufacturing activity eventually vanished from city centers and relocated to exurbs and rural areas — especially in the Midwest and South. Republicans have taken up the interests of manufacturers and have now come to embrace a protectionist agenda. Meanwhile, several moribund manufacturing cities, like Boston, Seattle and San Francisco, have reinvented themselves as global knowledge-economy hubs. Democrats had dominated these cities since the New Deal, and their constituents pushed them to embrace investments in science and technology, intellectual property protection, H-1B visas and, ultimately, globalization. Goaded by their respective geographic bases, the parties have also polarized on social issues like abortion and sexuality.

The Democrats have become a diverse collection of urban groups ranging from poor service workers to knowledge-economy professionals. The Republicans have become a coalition of exurban and rural groups ranging from manufacturing and natural resource extraction interests to evangelicals. Elections have come to feel like existential battles between different sectors of the economy and different ways of life.

Is this type of urban-rural polarization inevitable? After all, other industrialized democracies also developed a partisan cleavage based on economic policy in the era of manufacturing. Those countries, too, experienced social upheaval amid debates over gay marriage and abortion, and grappled with discontent as their economies globalized and prosperity moved to knowledge-economy cities.

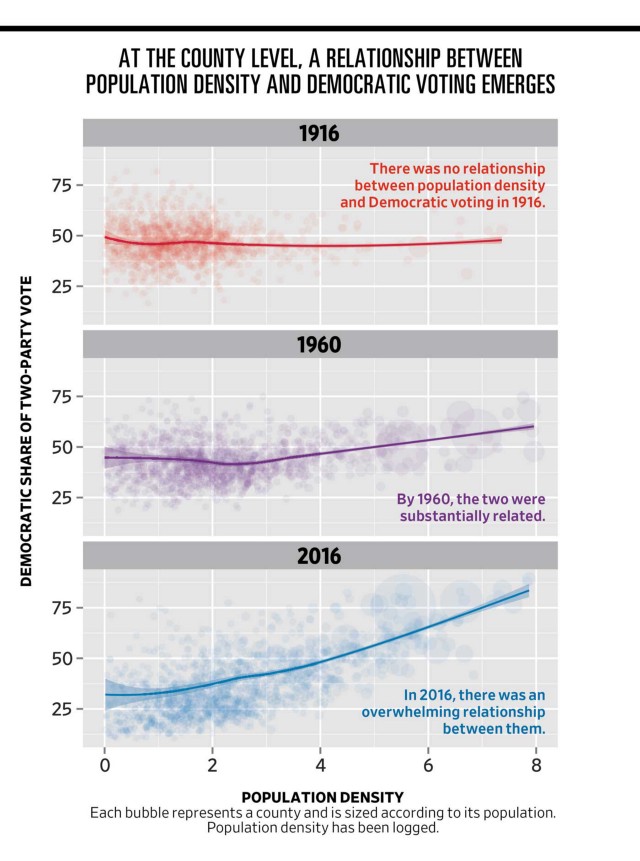

Graph: Courtesy Jonathan Rodden

Graph: Courtesy Jonathan Rodden

Urban-rural conflict is indeed on the rise in many countries. However, most industrial democracies have political institutions, such as a multiparty system with proportional representation, that lower the barriers to entry for political parties. In multiparty systems, all urban interests need not be bundled together in one party. In Europe, affluent, professional, urban social progressives (think Silicon Valley libertarians) often vote for liberal parties that coalesce with the right. The urban “campus left” votes for Green parties. Socially conservative members of trade unions often vote for Christian Democratic parties. Thus, European elections do not feel like civilizational urban-rural battles, and unlike in the United States, governments of the right often include significant input from urban representatives.

American geographic polarization has emerged in large part because our political institutions have created a strict two-party system that has gradually come to reflect a set of social cleavages that are highly correlated with population density. All the social changes that have pulled cities and rural areas apart since the 1930s have come to be expressed in the party system. Even though each of us might have a complex mixture of political beliefs that vary from one policy issue to another, we are forced to choose between an urban policy bundle and a competing rural bundle. An urgent question for the United States, with its history of geographic sectionalism and civil war, is whether the two-party system can continue to function if the parties are little more than labels organizing a bitter geographic conflict.

Jonathan Rodden is a professor of political science and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution.