The Dalai Lama and the Stanford neurology professor had some questions for each other.

William Mobley, director of the Neuroscience Institute, journeyed to Dharamsala, India, site of the Tibetan government in exile, to invite His Holiness to visit the Farm. Would Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso (“Holy Lord, Gentle Glory, Compassionate, Defender of the Faith, Ocean of Wisdom”) be willing to participate in a public conversation about the mind and the brain with several neuroscientists and Buddhist scholars?

The 1989 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, who holds the equivalent of a doctorate of Buddhist philosophy, said he would be pleased to have such a discussion. But the 14th Dalai Lama couldn’t help asking a question of his own. “Three times he said to me, ‘Why don’t you go measure something?’ ” says Mobley, who is trained in neurology, pathology and pediatrics.

The Dalai Lama’s mischievous wit punctuated his two-day visit in November. Hosted by the School of Medicine, the Office for Religious Life and the Aurora Forum, His Holiness appeared before sold-out audiences at a meditation and teaching in Maples Pavilion, a conversation on nonviolence in Memorial Church and a discussion with scholars in Memorial Auditorium.

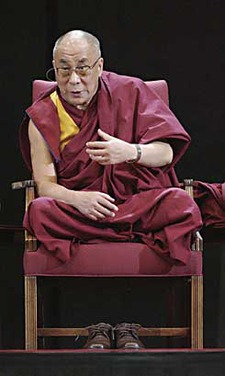

Several minutes into each session, the Dalai Lama untied his laces, removed his brown shoes and repositioned himself cross-legged in his chair. In the chancel of Memorial Church, the 74th manifestation of the Buddha of compassion talked with the Rev. Scotty McLennan, dean for religious life, about happiness and satisfaction. Most of his comments were translated by his longtime but soft-spoken assistant Thupten Jinpa. (“His English is better,” the Dalai Lama quipped when a microphone malfunctioned, “but my voice [is] better.”) In addition to hearing his insights on motivation and nonviolence, listeners also caught some personal glimpses: the Dalai Lama is 70 years old; he sometimes uses harsh words (but later regrets them); and he has tried to imagine Martin Luther King Jr. dressed in Indian attire (after Coretta Scott King told him about her husband’s fondness for Gandhi).

At the opening of “Craving, Suffering and Choice: Spiritual and Scientific Explorations of Human Experience,” Mobley observed that while Tibetan Buddhists meditate on compassion and neuroscientists look at brain circuitry, both have the same fundamental goal: alleviating suffering. “What can we do together?” he asked. “What’s the bridge going to look like?”

The panelists sat forward in their chairs as the Dalai Lama posed questions about imaging studies and how electrodes are used to stimulate regions in the brain. The neuroscientists and Buddhism scholars parsed the definition of craving and discovered they had very different concepts. Told about a drug that might suppress all cravings but also had the potential to render patients comatose, His Holiness said quietly, “That’s a disaster.” He seemed surprised by laughter from the audience, and added, “Truth speaks itself.”

Religious studies professor Carl Bielefeldt said “advanced Buddhists” could be helpful in studies of brain activity because they are “able to attain states in which ordinary perceptions are suspended.” Later in the day, Brian Knutson, assistant professor of psychology, echoed that. “Neuroscience is at a primitive level,” he said. “We need to study experts who can use their volition to change [brain activity].”

The Dalai Lama concurred. “There is potential for real interface,” he said. “I believe through such discussions we may find contributions [we can make] for the betterment of the world. My hope and my belief is that this kind of discussion will continue.”