CREATIVITY ISN'T NEW

Thank you for your fascinating article "Sparks Fly" about the d.school program (March/April). It is heartening to learn that creativity is alive and well at Stanford, and in the School of Engineering, no less. I'm a little dismayed to note that you treat this program as if it happened in a vacuum without reference to the many unusual, offbeat and creative programs that have emerged from this wonderful place that you now are stewards of and which many of us called home for four or six years a long time ago.

In my day there was an architecture program (imagine that) that emerged as a kind of stepchild of the art department and had its office next to a funky wood shop in the basement of the (then) Art Gallery. We enjoyed the persistent creative input of Professor Victor Thompson, contributions from well-known architects who volunteered their time, and of course all the creative resources of the art department including especially the design classes of Matt Kahn. Some of the stories about the d.school remind me so much of this program. Nobody came to Stanford to study architecture in those days, so we were a motley assortment of seekers from other departments looking to add a jolt of creativity to what some of us saw as a humdrum curriculum in other departments. I was a renegade from civil engineering, and after one quarter in the architecture program never turned back.

In our senior year a group of us persuaded the University to hire us to research some of Stanford's history and prepare a series of displays that could be shown at various alumni functions. We called ourselves the Student Projects Group. In the course of our amazing research in various archives we learned a lot that was unknown to us about Stanford's history. We learned, for example, that in the early days students were allowed and even encouraged to set their own curricula so long as they could get a professor to vouch for them and sponsor their intended program. Cross-fertilization amongst the various departments and a creative approach to education was evidently an early aim of Stanford's first president, David Starr Jordan.

As an outgrowth of our work we were given the opportunity to teach a class that we called Art and Communication. We were offered an old house on campus and given a small budget. The projects were entirely generated by the students, working in self-selected teams across many lines of background and experience. From this came some remarkable proposals, including one that a group nearly succeeded in selling the University on the idea of sponsoring: a pavilion for the forthcoming Seattle World's Fair exploring the concept of indeterminism in art and science.

What a joy to learn that encouraging creativity is still a vital part of the Stanford scene. I suppose creativity must include some bad ideas as well as good ones. Notable in the former category is the idea that an article on art and creativity could be introduced by graphic design featuring truly tasteless colors and fake-looking lettering. The lettering by the young student in the photo is better. Such a cute trick only serves to make fun of the very serious subject you are addressing: What is the role of creativity in our complex world? With a little luck it will lead to things that are both clever and beautiful.

Alan Jones, '61, MA '63

Mill Valley, California

MATH, EAST AND WEST

Ian Morris ignores Western limitations in numerical literacy ("Weighing History," March/April). Until we acquired an Indian system via the Arabs, we could only do integer math. We had no zero, no decimal point, and we needed more and more numerical symbols as quantities increased. Essentially the West had nothing beyond variations on Roman numerals. Details differed slightly in Hebrew and Greek systems, for example, but fundamental limitations remained the same.

Imagine trying to do contemporary science and engineering with roman numerals. It would also be hard to imagine a universe going back billions of years and spanning about as many light years when your numbering system conks out at 10,000 (a "myriad"). The Judeo-Christian Talmud/Bible set the age of the Earth at some 6,000 years. Could this have happened because their number systems were already struggling? With a superior number system, Hindu cosmography imagined a universe progressing through cycles of creation and destruction lasting billions of years.

A treatise on the Indian numbering system was translated from Arabic into Italian in the 12th century. Morris's graph of social development vs. time shows dramatic acceleration beginning shortly afterwards. Mere coincidence?

David Mason, '68

Culver City, California

In Joel McCormick's pleasant and balanced writing about Professor Morris, he mentions "Nightfall," Isaac Asimov's classic short story. Wonderful, but how could he have neglected mentioning [Asimov's futuristic character] Hari Seldon, the first psychohistorian? Of course, Hari is now merely the second.

Dennis Ashendorf, '79

Costa Mesa, California

QUAKER CONNECTION

Nice article on Herbert Hoover ("Waging a Kinder Cold War," Farm Report, March/April). One thing missing is the Quaker connection, which is so often overlooked (afsc.org/story/quakers-launch-postwar-feeding-program-herbert-hoovers-request).

American Friends Service Committee volunteers had extensive experience overseeing German POWs in France during World War I and carried out Hoover's food program in Germany.]

Charles E. Thomas, '62

Benson, Arizona

TRY RICE

The article "What Does North Korea Want?" (Farm Report, March/April) leaves the solution, i.e. talking to them, up in the air. Try the following: Donate the entire American rice crop to the people of North Korea in sacks that read "To the people of North Korea from the people of the United States. Thank you for being our ally in WWII." This would cost less than one day of war, without casualties. Stops starvation!

Geri W. McCray-Isaacs, '59

Westlake Village, California

FARM FRAGRANCE

As a parent of a recent Stanford grad, I found a kindred spirit in Jennifer Kavanaugh ("Eau Stanford, Where Art Thou?" Class Notes, March/April). I, too, have been a bit obsessed with what "smells like Stanford." Even the suitcases of dirty clothes my son brought home to Chicago smelled sweet to me, infused as they were with Eau Stanford. The scent still lingers in some of the clothes he left at home—every once in a while, I can open a drawer in his room and catch a bit of it. Thanks to Kavanaugh for solving the mock orange mystery for me. Combined with eucalyptus and jasmine, it's my favorite fragrance.

Kim Inman

Palatine, Illinois

NO EASY AUTISM ANSWERS

As a father of a 4-year-old with autism, I sympathize with Steve Su's letter ("Autism's Unknowns," Letters, March/April) revealing a sense of isolation from families with unaffected children. As a family physician with a busy pediatric practice, I also sympathize with his (apparently former) doctor who tried to reassure him there was no connection between vaccines and autism.

I don't feel my conclusion is ideological, as Su suggests, but one borne of the best scientific evidence on offer. An elegantly performed cohort study in Denmark of more than 500,000 children, for example, found no difference in the rate of autism between children who received the MMR vaccine compared to those who didn't. Critics pointed out that perhaps it wasn't the vaccine itself, but mercury-based preservatives; further studies debunked this hypothesis.

I regret, as Su does, that mainstream medicine has little to offer in terms of "biomedical interventions," but I'm sure his children have benefited, as my daughter has, from a surfeit of speech, occupational and other therapies. Just because some alternative therapies (like the potentially dangerous chelation therapy he notes) have been reported by some parents to be helpful doesn't mean they're necessarily worth sinking public research dollars into. Maybe they would be, if there were evidence that autistic kids had heavy metal toxicity, which chelation can treat—but there is no such evidence.

Furthermore, we probably ought to stop studying the purported link between vaccines and autism, because there is no good evidence suggesting otherwise, and the dozens of studies demonstrating vaccine safety so far have been unable to sway most vocal vaccine skeptics. You can't prove a negative, and it's fruitless to sink millions of dollars in further such studies if skeptics won't believe the results in any case.

The research he asks for about what therapies work for autism is out there, even though it's not glamorous. The evidence for special diets, megadoses of vitamins and chelation is poor. The good evidence is that prolonged one-on-one behavioral interventions work, to the extent that anything does. I want him and all parents of autistic kids to realize there are no easy answers, and there is no conspiracy; there is only hard work to be done. The way I put it to my patients' families is this: "If there was a magic wand I could wave, believe me, I would have waved it already. There isn't. We'll work with what we've got."

Daniel Rosenberg, '91

Portland, Oregon

I am grateful for the commendable work by Stanford researchers to unlock the biological underpinnings of autism ("Uncloaking Autism," January/February). However, I must disagree with the assertion that understanding the biology is "more fundamental" than understanding why there has been a hundredfold increase in the rate of autism over the past two decades (and also why it preferentially affects boys in a > 4:1 ratio). I was also concerned that the article seemed to downplay the severity of the autism epidemic by stating that the explosion in cases is mostly due to an increase in awareness of the diagnosis. This complacent explanation contradicts the recent results of the UC-Davis MIND Institute [Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders] and undermines the urgency and anguish expressed in the names and periodicals of parents' groups (e.g., Generation Rescue, Age of Autism). The attempt to blame older moms and preemies (presumably those under three pounds) also rings false, since these don't add up to more than 5 percent of cases.

When I learned I was expecting a baby boy four years ago, and read that boys have a 1 in 90 (now 1 in 70) chance of being diagnosed with autism, I naturally was concerned and asked an expert friend what was causing the epidemic. She said that nobody really knows, but that one leading theory is that an upsurge of marriages between "nerds" is producing genetically autistic children. This explanation caused me genuine anxiety until I realized it was preposterous. Ultimately, no genetically based theory can explain the exponential rise in autism (the human genome doesn't mutate that quickly) and it also leaves parents, especially those of little boys, feeling anxious and helpless to protect their children. It is puzzling that the bulk of autism research focuses on genetics rather than on environmental triggers, both pre- and postnatal. I deeply wish the Stanford scientists success in finding effective treatments for those already diagnosed with autism, but I believe it is at least as critical to focus research on preventing future children and their parents from facing this heartbreaking diagnosis.

Cynthia Nevison, MS, '88, PhD '94

Boulder, Colorado

I was so disappointed in my alma mater after reading "Uncloaking Autism" that I promptly threw the entire magazine in the garbage. My husband and I are both alumni, and we have a 17-year-old son who has what we are absolutely convinced is "vaccine-induced" autism. There is no excuse for the information you printed stating that it has been proven that vaccines do not cause autism. On the contrary, there is a growing body of evidence that implicates vaccines in the current epidemic of autism, and in a host of other childhood illnesses and disorders.

It is my hope that someone who writes for Stanford will take the time to read Vaccine Epidemic by Stanford alum Louise Habakus, '85, MA '85, and Mary Holland; The Age of Autism by Dan Olmsted and Mark Blaxill; and Vaccines: Are They Really Safe and Effective? by Neil Miller. If anyone can read Vaccine Epidemic and not shudder at the vaccines they've allowed into their children's bodies, and their own, then I will be beyond shocked.

I know what we saw in our own house. After every successive vaccine, our precious son slipped further and further into the abyss of autism. It wasn't just "coincidental timing," it was vaccine devastation at its worst. Please educate yourselves and do a follow-up article.

Laura Hayes, '87

Granite Bay, California

Uncloaking autism, like uncloaking any other of the recently multiplying diseases (from Alzheimer's to obesity) requires looking at their relationship with allergies: nutritional and endogenous. Take allergy [to mean] excess of energy. As a NAET [Nambudripad's Allergy Elimination Techniques] practitioner, I have solved a number of such cases just by following the instructions I received as a trainee. Don't discard the responsibility of vaccines too hastily, as there are diverse possible causes, but—in my opinion—the major cause is the presence of chemicals in food (coloring, flavoring, preserving).

As a scientist involved in neuroscience research as early as the '60s, I recommend that any rigorous bottom-up research must be complemented with more approximate top-down research (not just behavioral) for uncovering the clues toward the global destructive processes and their healing processes. Typically, the role of glial cells and neurotransmitters is currently underestimated, as well as the physiology of bodily meridians.

Michel Depeyrot, MS '66, PhD '68

Corenc-Le-Haut, France

MORE MOVIE MEMORIES

The article on "Flicks" ("What You Don't Know About," Farm Report, January/February) states that Flicks has been a Stanford tradition "since the 1960s." That statement understates the age of the Stanford Sunday night movies by more than a decade. When I entered Stanford as a freshman in September or October of 1949, one of the highlights of the student body week was the Sunday night movies.

I love Stanford. It keeps me in touch.

Arnold H. Gold, '53, JD '55

Studio City, California

FACE TIME

Thank you for Joan O'C. Hamilton's "Separation Anxiety" (January/February). I appreciate that researchers at Stanford are investigating what many of us intuitively know—all this time spent online is not good for us. What's most frightening is that we don't know the full impact online time is having on our kids. It's not only their excessive online time that's a problem, but also the time we parents spend online. How many things are we not doing because we're online? I think it's down time, conversations with family, reading and the pursuit of other fulfilling hobbies that suffer when we don't turn off our phones and computers. We don't need to "ponder whether people need to establish technology-free zones." Instead, I think we need to establish them in our families to maintain the emotional and social health of our kids and ourselves.

Clifford Nass's observation that, "It's becoming perfectly okay to use media while we're interacting," is a sad symptom of our ever-devolving social abilities. We're losing our focus on the real, face-to-face relationships that make life meaningful, and not modeling for the next generations how to treat live people. I will await the results of Nass's study on preteen girls and hope that Stanford will publish the findings. In the meantime, I'm keeping my 12-year-old off Facebook and having her invite friends over instead. I'm grateful to be part of an industry (summer camps) that gets kids outdoors, off their computers and cell phones, and relating to people face-to-face.

Audrey Kremer Monke, '88

Clovis, California

'RIGHT-WING PROPAGANDA'

I was intrigued but somewhat disappointed by Corinne Purtill's recent piece on Gretchen Carlson, the hostess of Fox & Friends ("Up and At 'Em," Planet Cardinal, January/February). It's fine with me that the magazine features alumni without regard to political ideology, and I'd be delighted to see it feature prominent conservatives. But Purtill's piece, while allowing Carlson to brag about her tell-it-like-it-is independence, does injustice to the facts and lets her get away with blatant misrepresentation. Fox & Friends is not an independent news-and-feature show. It is a right-wing propaganda show, and Carlson is the propagandist in chief. I watch it a good deal—out of curiosity and amusement. It's inadvertently hilarious because it's so feckless in trying to seem like what it is not. Indeed, Jon Stewart's Daily Show regularly skewers Carlson because she is really his unacknowledged counterpart, a clown princess of the GOP base. Carlson pulls off the trick of superficially displaying a wholesome, warm, Midwestern American spirit, while in fact she pumps up and cheerleads her right-wing guests, looks shocked and angered as she questions the rare Democratic guest, and generally uses Fox News rhetorical questions, not very subtle innuendos and selective editing to ensure that the Fox network serves its rather transparent mission. In fact, she coordinates reading of her script from her producers with the typical Fox News "chyrons" on the screen ("Democrats Trying to Bring Socialism to America"). The magazine could have treated Carlson respectfully without allowing her to reinforce her contrived image.

Robert Weisberg, JD '79

Stanford, California

CUTTING HEALTH CARE COSTS

President Hennessy's column on reining in entitlement programs mentioned two ways to control health-care costs: focusing on prevention and increasing "efficiency" ("To Save Innovation, Tame Entitlements," January/February). Yes, these would help, but they are like flies on an elephant. There are only two ways to fix the out-of-control costs in our health financing system, and both are achieved by expanding our single-payer system, Medicare, to everyone.

First, we need to eliminate the health insurers in order to recoup the 30 percent of our health-care dollars they spend on administration, CEO bonuses, marketing and shareholder profit. Plus, who needs a middleman industry that makes a profit only by denying care? We should treat health care like we treat schools, highways and the military—something we all need that is paid for by our taxes.

When government is the sole payer of health-care costs (services remain privately delivered), it has the power to negotiate global budgets with hospitals, and negotiate fees with physicians, pharmaceutical companies and all other providers. Without global budgeting, cost control will never be achieved.

All developed nations provide national health insurance to all their residents. We're the last on the block. Other countries spend half as much as we do and live longer. Clearly, the way to save Medicare is to give it to everybody.

William Skeen, MD/MPH, '76

Oakland, California

Correction:

In photo No. 2 of our reunion coverage ("Together Again," Farm Report, January/February) the "guest" of Robert Logan, '70, should have been identified as Kathleen Hamm Logan, '70, his wife.

The following letters did not appear in the print edition of Stanford.

DESIGN LEGACY

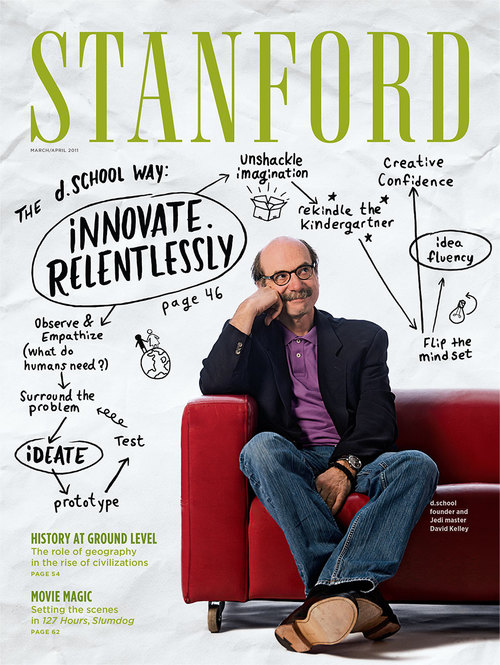

As an alumnus of Stanford's graduate program in design, I enjoyed reading about David Kelley and the success of the Hasso Plattner Institute for Design ("Sparks Fly," March/April). The article states: "The fundamental nature of an assignment has been overhauled. . . . The d.school approach is to designate squads of students as investigators of social or institutional conditions that pose challenges for human beings." As these design thinkers and makers go into the world, I encourage them to swap "assignment" for "client brief"—in other words, maintain the concept that design is most transformative when its practitioners aren't merely the providers of a commercial service but authors of a shared future. This idea—the "designer as author," originally theorized by graphic design scholars more than 15 years ago—applies equally to product designers. By seeking opportunities and initiating solutions that address fundamental human issues, designers will achieve the same cultural status in the 21st century that architects and artists had in the 20th. That could be the d.school's lasting legacy.

Steven McCarthy, MFA '85

St. Paul, Minnesota

I attended Stanford for two quarters in 1957, then for two quarters in 1960-61, for my MS in mechanical engineering. In the earlier period, I took a course in experimental stress analysis taught by the late Professor Harry A. Williams, with its lab in a small attic room in the engineering quadrangle. In the later period, I took a course in philosophy of design taught by the late Professor John Arnold in the same small attic room. Professor Arnold was also a consultant, and he had us work on real problems he had encountered, including coping with the signal time delay between Earth and the moon for an unmanned lunar vehicle steering system controlled from Earth. I found the course both fun and useful in stimulating "out of the box" thinking. This was a factor in my later patenting and manufacturing five industrial machinery shaft/coupling alignment tools, and two aimable air/sea rescue signal mirrors. At last count, the alignment tools had gone to 27 countries, and the signal mirrors to even more.

David Kelley seems to have carried the concept further, but he had an able predecessor in Professor Arnold.

Malcolm Murray, MS '61

Baytown, Texas

MORE ON AUTISM

I was alarmed to find that the lead letter to the editor ("Autism's Unknowns," March/April) contains a persuasive, well-written and utterly specious attack on immunizations. Thanks to your magazine, the author sends a message to parents throughout the Stanford community: Those shots pediatricians want to give your children might cause autism!

As I labored through the tortuous, misguided and misleading logic, I hoped for a follow-up response from the editor, perhaps a brief statement of fact: The overwhelming volume of scientific data has demolished any [causal link] between autism and immunizations. But no—the editor leaves the reader swinging in the wind, taking at face value some of the most dangerous rhetoric in the public domain.

I know journalists strive to show "the other side" of every argument. So let's see in STANFORD an equally persuasive screed that promotes The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fraudulent anti-Semitic text describing a Jewish plan to achieve global domination. Or how about a racist rant authored by an Exalted Cyclops or a King Kleagle of the Ku Klux Klan? Yeah, right—in a pig's eye. No politically correct editor would touch such nonsense with a 10-foot pole. Yet here's the irony: Only a tiny minority of Americans embrace anti-Semitism or racial hatred, and no dangerous groundswell threatens the day-to-day security of Jews or African-Americans. On the other hand, hundreds of thousands of parents throughout North America and Western Europe, fearing an "epidemic" of autism, have put their children in danger by refusing immunizations.

Even as I type this, rest assured your poisonous lead letter is racing across the Internet, adding credibility to a life-threatening movement. After all, it was published in STANFORD—what more persuasive venue could the author have found?

I regret the fact that your magazine is sent to me at no cost. Otherwise, I could express my anger by canceling my subscription.

John Gamel, MD '71

Louisville, Kentucky

I emphathize with Steve Su, whose 4-year-old twin boys have been diagnosed with autism. His letter raises more questions than he might think. As someone who once considered graduate work in the field of gifted children with disabilities, I had no idea that my future would include one such child.

In 1983 there was no awareness of autism among parents I knew, most of whom were associated with the medical field. Then, in Los Angeles, a couple with "a child called Noah" published a pioneering book about their severely disabled son. As is true of all mysterious and difficult disorders, it is the family that first seeks answers and joins with other families of sufferers. At UCLA a group of parents discovered one another and over the years developed a program for children with autism. Now that cohort has grown up and the program has continued in the private sector, where my thirtysomething son and I found someone to test him (finally) for autism.

The test identified him as probably autistic, but "well-compensated." That, in brief, covers a very subtle, but profound set of questions that had gone without answers for the better part of his life.

We have to do better than this!

Look around you. Among your cohort, I would venture, are autistic individuals. We used to call them eccentric, reclusive, socially afflicted, among other phrases. I would simply say that there are many different ways of being human. Among the diagnostic category of autism is such a varied range of "different" behaviors and characteristics, that the typology exemplifies the primitive state of our knowledge about the condition. Moreover, the word itself signifies only the most seriously disconnected among those diagnosed, children and adults who seem to attend only to a private world.

Many autistic people pass for "neurotypicals," as they call us.

Some autistic people, like Steve Su's twins, demonstrate exceptional skills. I Was Born on a Blue Day is the autobiography of the man who has calculated pi to the greatest extent. He sees words in colors (thus "blue" means Tuesday, not depressed).

Savants, like autism itself, befuddle and awe us. Dostoyevsky wrote The Idiot over a hundred years ago, and it remains one of the better insights into autism (linked to epilepsy, in this case). Prodigious skills among savants range from math to music to foreign language skills and can reach unexpected destinations in logic, aesthetics, art, spirituality and psychological insight. In short, autistic savants may actually be more human than most of us in many ways and afford us a glimpse into ways the human genome may develop (or is developing) in the future.

The cost of such prodigies is also great. The "real world" is an alien place for some of them, just as many of us regard the autistic individual as someone from another planet. Most common are difficulties with relationships and jobs, both of which require skills that autistic individuals struggle to learn. Autism, no matter how subtle and invisible leaves the individual vulnerable to misunderstanding, blame, ridicule, ostracism and developmental delay. What is simple for me is difficult for my son. What is easy for him, is impossible for me. This leaves the parent with a huge ache in the heart.

As acute as the need for real science to develop a more reliable understanding of autism may be, even more necessary is for all of us to include autism in the category, "ways of being human." It is nothing to be hidden, but to be included among us and accepted.

When I see an extraordinary performance by Robin Williams, hear the analysis of a polymathic colleague in a new social science, listen to Mozart, or spend a day with my son, I don't ascribe their uniqueness to something "disorderly." I wonder at it all, where did it come from, and what kind of multiverses do such behaviors inscribe? Why autism? Before there were vaccines, there were autistic people. Any departure from the statistical norm in genetics tends to signify an anomaly in the DNA or the developmental menu or the environment of the organism as it develops. Could the incidence of autism go up with age of parents at birth of the child, since both seem to be increasing? Could autism be related in some way with the "anomaly" of higher-than-the-norm intelligence in families? Could it have anything to do with fertility treatments, also increasing? These possibilities and more need to be seriously explored.

All of us have a stake in knowing about a segment of the human population that is treated much like the "deaf and dumb" of yesteryear. As we learn, we improve our acceptance of all humanity and correct our brutal ignorance.

Yes, Steve Su's boys are loving and lovable, as is my son, who has taught himself arcane languages, deejayed a radio show on ethnomusicology, published a paper on palm trees in an international journal, written a dictionary of Jamaican creole, and can instantly master any unfamiliar material and zero in on the most important questions. He needs major guidance with jobs, planning, decision making, girlfriends and financial self-support. Many autistics are really not that different from you and me; it is just that they are us in reverse.

Jean E. Rosenfeld, '61

Pacific Palisades, California

The fascinating article on autism requires a statistical explanation. To wit, "a disorder that affects 1 in every 110 kids (the rate is 1 in 70 for boys and 1 in 315 for girls.)" I believe what the author intended to say was "a disorder that affects 1 in every 110 kids, the incidence being 4.5 times more frequent in boys than in girls (the ratio is 1 in 70 for boys compared to 1 in 315 for girls.)"

Robert Conot, '52

Thousand Oaks, California

ON ENTITLEMENTS AND INNOVATION

In most respects I agree with the column by President Hennessy ("To Save Innovation, Tame Entitlements," January/February), but I was disappointed to see him join the Europe-bashing bandwagon. He wrote that the United States could spiral downwards "toward the lower growth rates and higher unemployment rates seen in Europe." I know that President Hennessy is aware that Europe consists of distinct countries with distinct policies and social structures, much more so than the various states within the United States. To lump them all together and paint them with one brush (inferior) is useful for chest beating, but it misses the chance to learn from success stories. What I love about Stanford is that no matter how good it may be, it is always looking for ways to be better. So why the blinders? I am an American who earned a PhD at Stanford, but I am an engineering professor in Sweden. I don't know the exact statistics right now, but I know from reading the Swedish press that Sweden has one of the highest research expenditures per capita in the world. This little country of 9 million (about the size of greater Chicago) has two automobile companies (Volvo and Saab), two truck companies (Volvo and Scania), two gas turbine companies (Volvo Aero and Siemens), an airplane manufacturer (Saab), a large pharmaceutical company (Astra Zeneca), a phone manufacturer (Ericsson), a major paper products company (SCA), big paper and steel industries, windmill manufacturing and much more. Large investments in education have produced a highly skilled and motivated work force. Sweden has the highest GNP growth rate in Europe and unemployment rates below that of the United States, official and unofficial.

Yes, taxes are high, but if you look just at taxes you miss the big picture. Take one small example: 30 percent of my energy bill is an energy use tax. That sounds horrible to Americans, but my overall energy bill is the same as in the United States. I have a much more efficient heating system here, and the development of it was driven by the tax. The tax revenue pays for energy research.

Sweden has universal, single system health care that works. (It's about as good as the high-end plan I had the last time I lived in the Bay Area, but much simpler to use.) It has a threatened but solvent pension system: Sweden faces the same threat as the United States, but they are addressing it, including raising the retirement age from 65 to 67—with some resistance, but it is not strong. Sweden has an excellent public transit system, and college is still tuition-free. My sons go to high school in the International Baccalaureate system. They have 5 to 10 students in each class and excellent teachers from Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. Their education is as good as a private education costing at least $25,000 [per year] each in the Bay Area.

Don't get me wrong. Sweden also has problems. My point is that a system often dismissed by leadership within the United States actually works quite well. Yes, the United States faces a lot of problems and we should also be proud of Stanford's success, but the blinders need to come off. There are useful lessons to be learned outside the United States.

Mark Linne, MS '79, PhD '85

Gothenburg, Sweden

While I did not read the article "To Save Innovation, Tame Entitlements," (President's Column, January/February), I feel a need to comment on Sandy Perry's letter defending government "entitlements" ("Dividing the Pie," March/April).

While there may be basic human rights enumerated in the International Declaration of Human Rights as food, clothing, housing, medical care, unemployment insurance and social security in old age, that does not mean that we all agree to them. In my humble view, food, clothing and housing (shelter) are our species' basic needs, but not rights. The other items enumerated are not rights, but "nice to haves."

Sure, all of these are good things, but nothing a government must provide. I can find no place in either our Constitution or Declaration of Independence where these things are mentioned. Our country and system are great because they provided the freedom to pursue our own destinies with minimum government interference. We are offered the pursuit of happiness—not the guarantee.

In the 20th century we strayed so far from this philosophy that our young generations, scarily our leaders of the future, see the government as the source of all things good. In fact, it should simply be an entity in the background that provides for the common defense and offers a framework for our successes and failures.

Our government is not a charity. We have seen recently that those governments that believe they are charities are going bankrupt and are seeing rioting in the streets by people who have become too dependent on government support.

Americans are the most charitable people in the world. Were we to do away with entitlements, private or religious based charities would pick up the slack for those truly in need. Perhaps we would even see those amongst us who are habitually on welfare (a non-euphemism for "entitlement") take up those jobs "Americans refuse to do" (only because they are paid not to do them).

Incidentally, I don't see a need for government charity in the corporate or academic worlds, either. If meaningful research really needs to be done, let the industries that need that research pay for it.

Bill Lorton, '64

San Jose, California

Forty-five years ago, I saw a strong university finance its research through private enterprise (Stanford Research Institute) and the needy receive donations from caring Americans. These activities were the victims of politics: SRI, because of defense contracts during Vietnam; and private charity, because elected officials wanted to take the guilt and embarrassment out of charity or wanted to win votes.

Now universities are jealous of government charitable activities and needy people must riot and demonstrate in the streets to protect their "entitlements" (charitable money). In the meantime, taxpaying American don't want to pay taxes for government-provided university research and entitlements. (Through this vehicle, taxpaying Americans don't experience the grace of charitable giving, and the government is not perceived as an efficient vehicle for distributing entitlements.) So America is becoming a failing debt-ridden country (public debt is 70 percent of GDP), and a battle is increasing between taxpaying and entitlement-receiving Americans.

Fortunately, my crystal ball shows that America or its successor will not be able to continue providing money for these activities. Then capable universities will reutilize their creativity to sell inventions or increase direct grants from individual foundations, and Americans will directly help the needy through charitable organizations. Americans have wealth, rather than America. Americans don't like paying taxes, but Americans do help other Americans who are not able to fulfill their own needs.

Herb Smith '60

Yorba Linda, California

VIRTUALLY DYSFUNCTIONAL

I find it quite ironic that Dr. Elias Aboujaoude would natter on about Internet use disorders ("Separation Anxiety," January/February) and then in the next breath (or Tweet?) boldly announce, "To be a functioning member of society you have to be online." Apparently it's dysfunctional if you do, and dysfunctional if you don't.

Katherine A. Hinckley, MA '63, PhD '71

Fairlawn, Ohio

Address letters to:

Letters to the Editor

Stanford magazine

Arrillaga Alumni Center

326 Galvez Street

Stanford, CA 94305-6105

Or fax to (650) 725-8676; or send us an email. You may also submit your letter online. Letters may be edited for length, clarity and civility. Please note that your letter may appear in print, online or both.