Game Plans

“Game Changer” (September/October) offers an interesting argument, but regarding football, it strikes me as somehow self-deceptive and melodramatic in spite of the Pac-12 presidents’ proposals for reform. As I see it, the NCAA is finished as a going concern; the only question is how fast or slow its demise will be. When I see bulletins on the Stanford athletic website about Stanford in the NFL, read Coach Shaw’s comments about his players’ NFL readiness or learn how Stanford freely offers its facilities as a tryout location for the NFL, it’s hard for me to take claims of amateurism seriously.

If students work at the university to defray their educational expenses, are they any less students, or any less part of campus life, even though they are also employees? Whether or not Stanford’s football squad votes to unionize, I think that principle applies to them, as well as to graduate students working as teaching assistants. To use students in any capacity as employees while pretending they are not is dishonest. And if Stanford can find the way to raise money for bricks and mortar, it seems to me that it can do the same for its people.

The article does suggest a way out that might preserve both academic and athletic integrity and prominence at Stanford, and benefit all its teams, though I wish it had gone farther. Imagine a conference that includes not only Stanford, Rice, Tulane, Vanderbilt, Duke, Northwestern and Notre Dame, but also some of the public Ivies such as Cal, Michigan, Texas, North Carolina and Virginia. A big-time national conference that insisted its athletes remain in good academic standing, retained them even if they sustained career-ending athletic injuries, and covered all their financial needs on the way to their completing their studies would be worth having, wouldn’t it? And if Cal were in it, we’d still have Big Game.

John Raby, ’66

New London, New Hampshire

President John Hennessy [gives] the correct answer to the dilemma the article raises: “sports like football would essentially become mercenary enterprises—a professional minor league. In that event, he asks, ‘Why be involved in it?’”

Both pro football and men’s pro basketball now have a variety of minor or developmental leagues; simply allow them to expand, independent of the universities, to major cities where major college teams now play, paying the players and coaches as they develop toward the top level. Pro baseball already operates that way, with college teams and pro minor leagues providing two different paths. Colleges can have students play sports in intramurals as they now do but could also provide limited unpaid interschool competitions for the best student-athletes who want a little higher level of competition. Those who want professional competition can play for professional teams with no academic affiliation.

This solution is so obvious and simple that it can never work. Alumni will never be on the cutting edge of change, and this is one of their sacred cows. The chauvinism displayed by college sports fans is a force few can stand up to.

I do wish Hennessy luck in this “one last shot at restoring the primacy of the academic role for student-athletes.” But I fear—like failing to convert to the metric system, recognize the existence of Cuba or eliminate the expense of using pennies as currency—the tradition of professionalized amateur sports will continue or worsen, in spite of anything a few reformers or judges might say or do.

Steve Lawton, ’74

Santa Cruz, California

Anyone who participated in athletics knows that they offer unique opportunities for teaching discipline, teamwork, strategy, sacrifice, and how to win and lose—lessons not easily taught in the classroom—in addition to just plain being healthful and fun. But no one paying attention could possibly think that an educational mandate plays a significant role in major college athletics today. They are all about the money: money for the coaches, athletic departments, schools, advertisers, broadcasters, gamblers and producers. Money for everyone except the players, who provide this vicarious entertainment at great cost of time and energy and the loss of other, more diverse educational opportunities. I am proud that Stanford is universally considered the foremost example of excellence in both academics and athletics, while the academic reputation of the top sports schools seems inversely proportionate to their athletic standing. However, all the colleges Stanford would consider its academic peers—the Ivies, MIT, Caltech, Chicago, Hopkins et al.—have long since dialed back athletics to an appropriate educational emphasis and stopped seeing them as moneymaking entertainment ventures. Major college athletics are just big business today. Stanford should give the kids an education and stop exploiting them.

Thomas Barton, MBA ’71

Los Altos, California

With the rest of the world in 1976, I saw Nadia Comăneci, the Olympic gymnast from Romania, and Bruce Jenner, decathlon winner from the United States: two completely different athletes representing two completely different systems of athletic development. Nadia terrified me. Bruce Jenner thrilled me. I saw what I thought was perfection without passion and passion with intense focus representing the Soviet Union and the United States as superpowers in two individuals. Neither was driven by money, but neither was athletically developed in systems that seemed right. Yet would these athletes be where they were in 1976 but for the obstacles placed in front of them?

I followed their careers and life paths after 1976 to see how athletic success, fame and money changed them. Now, as an adult, I find I understand Nadia Comăneci and don’t understand Bruce Jenner. My theory has to do with the coaching. There is a difference between coaching a human being and coaching an athlete. Pay to play allows you to coach an athlete and not be concerned about the human being. Coaches can be effective educators when they are concerned about the character of the human being who happens to be a great athlete. The more appropriate question is who the coaches were for Nadia and Bruce. Ask the right question: Can the student-athlete develop as a well-rounded human being under pay for performance? I believe the answer is no. And I believe we are seeing today the consequences of coaching for performance and money minus character. Money for athletic performance does not last a lifetime and should not be part of the values or goals of an education.

Theresa Ellis, ’87

Bangor, Pennsylvania

As an alumnus of both Stanford and Notre Dame, I wrote a letter to Notre Dame Magazine regarding Notre Dame’s perpetual question of whether its football team should continue its historic independent status or join a conference. I suggested that it form its own conference, “The National Conference,” the other schools coincidently being those mentioned by Mike Antonucci and Kevin Cool—Stanford, Rice, Vanderbilt, Duke and Northwestern. I also included Boston College, another private university with both high academic standards and a major football program. The letter was written prior to the Northwestern NLRB ruling and shortly before Notre Dame’s announcement of its new football schedule arrangement with the Atlantic Coast Conference. For all the reasons mentioned in “Game Changer,” it may be an idea whose time may soon come.

As to reform of college football insanity overall, a partial but major answer would be to return to the future, specifically pre-1965: limiting substitution so that, like Owen Marecic, almost everyone could become “the perfect football player” playing both offense and defense; making freshmen ineligible, thus making room for freshmen and/or junior varsity football; and limiting the varsity schedule to 10 games. Where there’s a will there’s a way, but the will is currently lacking. As Scripture so accurately informs us, the love of money is the root of all evil, but the cost of that love, at least for schools like Stanford, may very soon prove to be too high.

Noel J. Augustyn, MA ’69

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Mike Antonucci and Kevin Cool make a persuasive case for Stanford’s student-athletes retaining their status as students. But there are many statements that confused me. For example, “Stanford would reject some potential changes, even if it meant withdrawing from major college competition.”

My confusion is about the basis for their authority. Are they officially speaking for the Stanford administration, faculty and students? Or is their article merely an extended op-ed?

Tony Lima, MA ’77, PhD ’80

Los Altos, California

Editor’s note: The sentence you refer to was based on interviews with university officials. As the article states, much is still unresolved, and specific institutional responses await legal and policy rulings yet to come.

I have a long history with Stanford sports. I’ve had season tickets for the football team for some years now. I’ve been to the last five bowl games. And I follow several of the other men’s and women’s teams faithfully.

I came to Stanford in 1968 on an athletic scholarship in a non-revenue sport. The scholarship covered tuition and fees. All other expenses—books, room and board, and everything else—were the responsibility of the student-athlete. I came from a blue-collar family with no money to give me for an education. I made up the difference by hashing in the food service and working in the athletic corp. yard. I remember hashing 12 hours per week for two quarters to get my meals without charge in the quarter of my sport. I worked up to 150 hours a quarter in the athletic corp. yard for $2.50 an hour. Of course I still attended classes, studied and trained for my sport every day. There were several of us from different sports all doing the same thing.

My sophomore year, a friend got me an interview with the fire chief, who brought me in as a student fireman. We got our room and $60 per month for working every other night. About a dozen of us lived at the station, two to a room. My roommate, Dennis, was a center on the football team. I write this to let you know what was common for a scholarship athlete then. Although it was difficult to balance all the work, study, training and competing, I considered myself extremely lucky. Here I was at a prestigious university getting a top-notch education that neither I nor my family could ever have afforded. My Stanford education and the contacts I made have stood me well in my life.

Athletic scholarships open Stanford to a whole range of students who would never have the opportunity to attend on their own. Stanford is enriched because of these students, who bring a wide range of cultural and life experiences to the school that would otherwise be missing.

I did not come to Stanford to be paid to play. I came, just like all the other athletes I knew, because of the opportunity of getting a Stanford education. I strongly believe that if it comes to paying athletes in addition to their scholarships, Stanford should drop sports or compete in a division that does not give scholarships. If being paid to play becomes the deciding factor for an athlete, then the era of the “student-athlete” will come to a sad end.

Joe Virga, ’72

Redwood City, California

Regarding the potential for Stanford to participate in a new athletic conference comprising like-minded, highly selective colleges, three service academies—Army, Navy and Air Force—would also be excellent candidates for such a league. With the inclusion of these academies, this new conference would approach the critical mass of eight to 10 members. There are numerous other private universities, such as Boston College, Wake Forest, Texas Christian University, Southern Methodist University, Miami and possibly even USC, who will have to decide how they will participate in a brave new world of college athletics. I am hopeful that Stanford will be able to continue its athletic tradition, but in a manner consistent with and supportive of the university’s academic mission and priorities.

Peter K. Seldin, MBA ’80

New Canaan, Connecticut

Big-time college sports have metastasized to the point that they are no longer compatible with Stanford values or the Stanford student experience. So, rather than struggling to save a broken model, let’s vigorously pursue an athletics policy of participation for the many, not narrow professionalism for the few. Please let some lesser institution take Stanford’s place in the Pac-12 and Division I, and focus instead on encouraging every student to play intramurals, to run the Dish, to swim under the sun. I believe that a silent majority of alumni would welcome such a courageous move.

Mark Koops Elson, ’96

El Cerrito, California

Perhaps a bifurcation would work: Stanford Athletics and Stanford Academics. The athletic process would lead to a pro contract, the academic process to a degree. There seem to be sufficient similarities in these two pursuits to warrant serious consideration.

Sheldon Morris, ’54

Novato, California

Many thanks for the thoughtful, informative and balanced article. As an alum of both Northwestern and Stanford Law School, I am being asked regularly for my views on both the Northwestern football players’ NLRB initiative and the Ed O’Bannon antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA. Thanks to your article, I now have at least a basic understanding of these two initiatives and what some of the consequences may be if either of them succeeds, at least for Division I college sports programs and for schools like Northwestern and Stanford.

I am especially impressed with President Hennessy’s comments on the array of issues presented, together with the fact that, as you’ve reported, he has long been concerned about the “increasing divergence between academic objectives for student-athletes and athletic objectives,” a divergence that may well be accelerated by these two initiatives and others that may follow.

As your article makes clear, change is coming, and whether a program such as Stanford’s, where athletic success has been achieved without compromising academics, will remain viable is in doubt. Let’s hope that, as the forces of change evolve, Stanford will continue to benefit from the quality of leadership provided by President Hennessy and those serving under him.

Sam Sperry, JD ’68

Moraga, California

I was a student at Cornell in the distant past when the Ivy League decided to de-emphasize football. The level of play in the Ivy League has certainly declined since then, but there hasn’t been any decline in the reputations of those schools (nor in their endowments). Stanford’s reputation is of a similarly high stature (Harvard being the Stanford of the East); if some change in the level at which Stanford competes in football must be contemplated in response to outside rearrangements, maintaining Stanford’s reputation should not be a factor in any decision. Its reputation is surely secure enough that any such change would not affect it.

Still, Stanford is a bright beacon, showing that smart kids can play sports at the highest level. It would be an enormous shame if that beacon were dimmed. I therefore support Stanford’s efforts to resist creeping professionalism in college athletics.

John S. Warren, PhD ’67

East Dummerston, Vermont

Excellent so far as it goes is Mike Antonucci and Kevin Cool’s cover story on commercial threats to Stanford’s ideal of the student-athlete. I would like to broaden the perspective and restate in brief a proposal I made in the March/April 2010 issue (“Bowled Over,” Letters).

Mike and Kevin described as the major threat the growing drumbeats and legal muscle toward football and men’s basketball players as salaried and unionized employees. The article deplored that fever yet ironically supported the idea of a degree as a strong preparation for “the workforce.”

A big reason why I applied to Stanford—and only to Stanford—was my firm embrace of a college education as having nothing to do with me and “the workforce.” I was a talented musician and in my last year in high school, prospects of entering the music workforce via great music schools like Juilliard and Eastman were floated my way.

I dismissed those prospects out of hand. I planned to make a living in music but I wanted to go to Stanford to enrich my mind and soul and spirit generally.

As a music major here on the Farm, my progress was largely as a lead composer for Big Game Gaieties of 1955 and 1956. My Stanford education was as I had envisioned it.

Dwight Eisenhower’s “Farewell Address to the Nation” is famous for its warning against the military-industrial complex, but it should also be famous for its warning against the academic-industrial complex: “ . . . the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are hundreds of new electronic computers.”

Today, in some schools, the curriculum itself is designed by corporations—workforce players possibly with fat government contracts. The academic-industrial complex in college sports is a subset of the academic-industrial complex generally.

Mike and Kevin detailed several things Stanford might be forced to do by those growing drumbeats and legal muscle. In 2010, I proposed that Stanford do something freely and of its own initiative: Refuse to go to a football bowl game unless the team wins nine or more games in its 12-game schedule. Reject the homage to mediocrity and the commercial whip of being “bowl eligible” with only six wins.

In the penultimate paragraph of Mike and Kevin’s article, a President Hennessy musing was quoted: “ . . . we have a lot of influence because we’re seen in a sort of unique place, and perhaps by staking out a position we could give people courage . . .”

Just so.

Adopt my proposal, Stanford. It’s a long way back up a very steep hill, but Dwight Eisenhower would cheer us on and some drumbeats would cease.

James T. Anderson, ’57

Palo Alto, California

Shaggy Dog Story

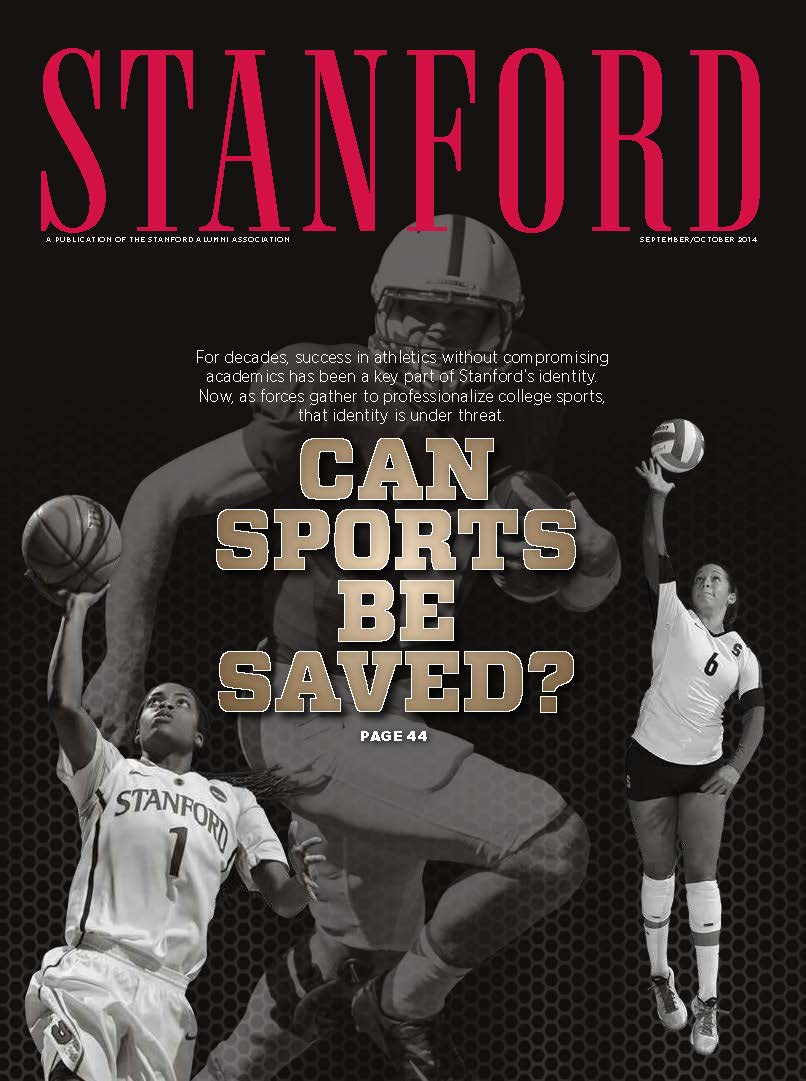

I really appreciate the timely and informative articles in each issue of Stanford magazine. But kudos also go to the staff who produce the publication, for their tasteful choices of advertisers/advertisements appearing in the magazine. I enjoy some of the infomercials almost as much as the articles! For instance, I didn’t get beyond the inside front cover of the September/October issue without noticing—as would all dog lovers—that a small picture of a Boston terrier is a “hidden” clue in the ad for Boston Private Bank. The canine seems to be a lookout as it helps students moving into dormitory housing (on the Farm, I assume), just as a banker would help clients steer their way into a new port. For the trivia fans out there, you might be wondering whether this breed originated in Boston (basically, yes); or whether the Boston Terrier is a terrier as officially defined by the AKC (no); and if a Boston Terrier is not a terrier, what it is. Answer: It is in the “non-sporting” group as defined by the AKC; in fact, it was the first non-sporting dog bred in the United States and the first U.S. breed to be recognized by the AKC. Which leads us back to the cover “Can Sports Be Saved?” And if not, can non-sports be saved?

David C. Petersen, MA ’73

Sacramento, California

Eyes Wide Shut

I was very interested in your article by Nicholas Weiler (“A Bedtime Story,” September/October) partly because I am at the age where I have trouble getting to sleep at night, even when I am tired. However, there was one topic not addressed and one only touched upon. The topic not addressed is the mind-out-of-body experience, which could be best described as having your mind floating around the room while your body is in bed, asleep. When I was younger, I thought that everyone had that experience. When I became older, I discovered that most people don’t. The topic only touched upon is the paralysis aspect of sleep; perhaps that relates to the mind-out-of-body. I have personally experienced incidents where my mind was fully awake (I was aware that I was in bed), but my body was paralyzed and would not move (I usually concentrate on one toe or finger, willing it to move). That is a scary experience.

Fred E. Camfield, MS ’64, PhD ’68

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Thanks very much for publishing the article about Bill Dement. Those of us who have read and reread his book and especially the second chapter—the history—can appreciate how he built upon the work of Nathaniel Kleitman and created the world of sleep medicine. There are few health issues that are so important and fundamental as sleep. Dement’s work has reached not only the 20,000-plus students at Stanford but also far beyond the Farm.

Just recently, I tried to reason with a friend who had been in a serious car accident due to someone falling asleep at the wheel, suggesting that after a full day’s work [the travelers] get a good night’s sleep before driving to North Carolina. To no avail; they worked a full day and drove through the night, while filling up on coffee. Even those whose lives have been deeply affected by what you describe as “devastating consequences” often do not realize what happens when sleep is lacking.

I hope and pray that Dement’s work continues to reach those at Stanford and beyond. His “radical” way of thinking about sleep not only saves lives by preventing devastating consequences, but also helps all the body’s systems to work better.

Jonah G. Sinowitz, MA ’96

Lakewood, New Jersey

Puzzle Solved

Scott Allen did a great job on the “Scrambled Majors” puzzle (September/October)—it was very clever, difficult yet doable. As for your troubled undergrad, Ms. Graham, I have two suggestions. First, she needs a GOOD GIN TONIC, and secondly, she should __ O __ __ __ O __ O __ __ __ __.

John Stahler, ’60

Mountain View, California

Answer: Go into coding.

‘Unprecedented Cooperation’

The iconic photo of that huge Ford Granada crushed by chunks of Old Chem’s sandstone façade caught my attention and evoked personal memories of 5:04 p.m., October 17, 1989 (“His Lucky Day,” Farm Report, September/October). The marginalia accompanying the article included a list of several interesting statistics, to which I would add one more: In the 15 seconds that the Loma Prieta quake lasted, 20 percent of Stanford’s available classroom inventory—30 of the 150 designated classrooms—was rendered uninhabitable. As assistant registrar at the time, over the days following the quake I led a small crew from the registrar’s office working long hours in the Old Union to find space and reassign all the classes scheduled in those 30 inaccessible classrooms in time for the resumption of instruction the following Monday. The extent of willing cooperation from the schools and departments was unprecedented. The typical bureaucratic red tape was quickly cut or simply ignored, and many of the usually closely guarded departmental conference rooms were generously made available for classes. Thanks to the availability of an administrative computer system that weathered the tremor, classes resumed the following Monday with hardly a hitch. Our classroom team was, of course, only part of a much larger campus-wide emergency response, characterized by focus, efficiency and grace under extreme adversity—at a level unequaled by anything else I experienced during my long career in university administration.

Jack R. Farrell, MA ’79, PhD ’84

Davis, California

Hoover’s Long Reach

Very interesting tidbits about Hoover Tower (“What You Don’t Know About . . . Hoover Tower,” Farm Report, September/October). But one item was extremely surprising: The radio room “was originally used to monitor foreign military broadcasts and to transmit news from the Office of War Information to the front during WWII.”

Given the vast distances involved, it would be very interesting to know what technology was used to accomplish this, and why the tower (separated from the Pacific Theater by coastal mountains and thousands of miles of ocean, an entire continent away from the Office of War Information, and an additional ocean away from the European and North African theaters) would have been selected for this purpose.

David Rearwin, PhD ’73

La Jolla, California

Editor’s note: Our efforts to clarify are stymied for now because relevant documents are unavailable due to renovations at Hoover.

Medium and the Message

I just finished reading, from lead to closing sentence, “The Last of a Class”—something I almost never do (January/February 2013; republished at Medium.com/@stanfordmag). At the end, you asked for feedback.

Do keep the Stanford articles on Medium. I’ve always had such an “impression” of Stanford: inaccessible, faceless and, yes, even elitist. (Not that my degrees from Gonzaga are so bad.) Your article about Ephraim Engleman humanized a generation, and put a character to Stanford I would never have experienced or believed could be valued at the school. That you even took the time to care to highlight such a lovely alum speaks volumes about Stanford’s legacy, values and character that an admissions catalogue can’t convey, and student tour guides probably don’t even know.

I often chide my own college students to take the time to really talk with Grandma or Great-Uncle George about their lives during those times. I’m glad to see Stanford does that very thing as well.

Christina McCale

Olympia, Washington

Ties That Bind

Although I graduated 24 years back, Stanford remains a growing part of my life. The magazine reaches out to me regularly, deepening the bond. I felt inspired by the reference to “In Alumni We Trust” in the call for applications to join the Stanford Board of Trustees in the issue of July/August 2014. Alumni are bearers of the Stanford name and fame in all nooks and corners of the world, cascading the beacon of light emanating from the Farm.

I have a small story to share. In the early 1990s when I was heading Pakistan’s national oil company in Islamabad, a stranger dropped into the corporate office, passionately insisted on seeing me and was allowed in. He appeared distressed and dazed as he narrated the difficulties he had encountered sneaking out of Tehran, Iran, and making his way to Islamabad only to meet me. When he told me he, too, was a Stanford alumnus with a PhD in petroleum engineering, we were strangers no more.

He confided in me that he was an Iranian Jew facing persecution back home. Having heard of my Stanford connection, he took the perilous land route into Pakistan. He was fearful of being caught here and handed back to the Iranian authorities. Needless to say, I did all I could to get him visas for the United States, and his family sneaked out later to join him there.

Through its worldwide network of alumni, Stanford is as much an international phenomenon as the United States itself. I suggest we encourage and energize two-way communication [through] a new section of Stanford with an international alum volunteer as its editor. The aim would be to proliferate knowledge and improve the quality of education in underdeveloped countries. I further suggest adding an international alum as a virtual member of the Board of Trustees to give the board the same international dimension Stanford possesses.

The farther in space and the longer in time alumni are from Stanford, the stronger members of the fraternity they are.

Gulfaraz Ahmed, MS ’85, PhD ’90

Islamabad, Pakistan

Water Solutions

I found the recent article by Kate Galbraith on the California water crisis (“Tapped Out?” July/August) and the letters that ensued (“Water Ways,” September/October) to be very cogent. The referenced seawater desalination project in the Carlsbad Agua Hedionda Lagoon is only one example of a multiuse, sustainable, environmentally sound operation that also houses a natural-gas-fueled electric power plant, a commercial shellfish-producing operation, and a fish hatchery producing fingerlings to restock the endangered white sea bass population of the California coast as well as fingerlings for a commercial fish-production facility in Baja California—all in addition to the soon-to-be-completed, technologically advanced, energy-efficient and environmentally sound seawater desalination plant. In addition, the middle and inner lagoons have recreational activities and educational programs.

James C. Selover, MS ’52, PhD ’54

Carlsbad, California

In reading the letters in response to Kate Galbraith’s very fine article, I was greatly dismayed by the shallow and uninformed thinking manifest in several.

For example, Tom Hernandez blithely proposes the construction of desalinization plants every 100 miles along the coast, demonstrating little understanding of the complexity and costs associated with this process. One might ask: Why is it we don’t even have one plant operating at the moment? (It is the case that one is close to being launched.) It is beyond this letter to summarize the problems with his proposal, which include countless tons of concentrated brine that would need to be disposed of. Just Googling “desalinization issues” would be a good start to see sophisticated analyses on the promise and pitfalls of this technology.

Hernandez mocks the decision to “divert 150 billion of gallons of water annually into the Sacramento River Delta” and asks “Why will this water run down the drain instead of being used to irrigate crops or supply homes?” His lack of understanding here is startling. Water is not “diverted” to the Delta. It’s where the water of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers has always gone before much of it was sent to the Central Valley. Like all estuaries, the Delta sustains the biological health of a region. Two thirds of Californians depend on it for their drinking water. One of the most precious creatures in the universe—salmon, which are more important than any crop—and other species like sturgeon need a healthy estuary to survive. And yet the Delta is on the verge of collapse. How do we know this? Because Delta smelt populations are collapsing. This little fish, which Hernandez dismisses as “bait,” is an “indicator species”—the canary in the coal mine—which reveals the health of the Delta. It is the Delta we must save. All of this is basic ecology.

Kenneth G. Coveney also displays scant knowledge of science. He, too, denounces “the volume of water flushed through the [Sacramento-San Joaquin] Delta through the San Francisco Bay to save the Delta smelt.” Beyond his likewise ignorance of the web of life, that flushing water is critical to the health not only of the estuary but also of the Bay—also sick and collapsing—and of the ocean. For instance, sediment and nutrients “flushed” with water through the Delta and Bay replenish ocean beaches, which are critical habitat for many marine species.

We transform natural systems like the Delta and San Francisco Bay at our peril. Nature will always have the last say, as seen in ever increasing weather calamities and more devastating ones surely to come with more extreme climate change.

William M. Smiland claims that total deregulation will solve our water needs, positing that lack of precipitation and climate change are not the problems. Rather, it is the “new solicitude for wildlife habitat” that has brought about regulations, which are the problem. The main beneficiaries of deregulation are, of course, corporations such as oil companies, which find regulations getting in their way of ravaging the earth to maximize profits. Anyone who doesn’t recognize the interrelationship between protections, i.e., regulations, of “wildlife habitat” (the Delta and Bay are examples of such habitat) and the health of the planet and humankind is badly misinformed.

Ralph Wagner recounts ways humans have “helped nature,” but many of these technocratic schemes have exacerbated problems we now face. Filling in wetlands, for example, eliminated natural reservoirs wherein water could be stored. Many dams caused consequences, e.g., loss of salmon and steelhead runs, that have far outweighed their benefits. Water from north state rivers created lush gardens and urban metropolises in deserts, with little regard to the well-being of the rivers, their creatures and humans whose lives are attached to them.

I do applaud Robert West citing the city of Irvine’s reclamation efforts, including the use of gray water and wastewater. Such recycling of every drop of available water, along with wide-ranging conservation measures—replacing all lawns and exotic gardens with natural landscapes, growing less-thirsty crops and using more efficient irrigation methods—and massive groundwater recharging (underground reservoirs), would conserve and store tremendous amounts of water. That is a far more achievable multipronged strategy than the grandiose dream of building desalinization plants up and down the coast.

I am one of those environmentalists (whom Smiland calls “misguided”) who see the absolutely vital connections between the health of the environment and the health of humankind. I am shocked to see that some Stanford graduates are blind to any such connections and lack basic understanding of these crucial issues.

Bob Madgic, MA ’62, PhD ’71

Anderson, California

Author of The Sacramento: A Transcendent River

Good Timing

I enjoyed “Sheer Focus” (July/August) about climber Tom Frost. Tom and I both lived in the Donner wing of Stern Hall in the late ’50s. I’m not sure I agree with the “socially awkward” part, although perhaps I was just too socially awkward to see it. What I remember most about Tom was his ability to schedule classes during winter quarter only on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays in order to spend four-day weekends skiing.

Steve Brown, ’58, MS ’61

Alameda, California

Too Few Applicants?

In regards to Anne Jacques’s letter (“The Bigger Picture,” July/August), I have always considered myself to be a member of “The 200.” This was the number of women admitted to Stanford in 1933 above the number allowed in the Stanford will.

The reason for “reinterpreting” the will in 1933 was not the shortage of men in 1943, as Jacques asserts, but a shortage of applications due to the Great Depression. Also, the university’s heavy investment in railroad bonds and other poorly produced investments sharply reduced Stanford’s income. Today’s overwhelmed admissions committee could scarcely imagine!

I still feel most grateful for the admission exception, as I was admitted even as a transfer sophomore from Wellesley College.

I am also most appreciative of the students who have succeeded me with such remarkable scholastic and personal records. They have made me look smart by association.

Jayne Seydell Milburn, ’36, MA ’38

Wichita, Kansas

Living With Coal

I read with some dismay the way the university is reacting to the coal issue and to CO2 emissions (President’s Column, July/August). Selling the shares of coal companies to punish them or to keep the university away from the bad coal companies is immature, to say the least. To start with, coal producers are not the ones that contaminate. It is industries like the one I work for that do. My company, GCC, owns three cement plants in the United States plus three in Mexico. We burn coal. (We also own a coal mine in Colorado.) Similarly, you should dispose of shares of utilities, cement, steel, chemical and other companies in industries that do emit—not to say transport and dairy product companies. Concrete—mostly all cement is used to manufacture concrete—is the most friendly construction material, according to several MIT papers and research.

Coal is probably the most abundant fuel in the world, and today the cheapest. I just cannot imagine how we are going to prevent China, India and other developing countries from using coal. Measures like the ones Europe implemented with the Tokyo Round sent industries to Northern Africa and the Middle East. So now, on top of the emissions from manufacturing (cement included), the world gets the emissions from hauling products to Europe for final use.

Our industry is concerned about climate change and social responsibility in general. We dedicate our time and resources not only to comply with local law, but also to go above and beyond. We have an initiative with the World Business Council that gives us guidelines in several of the contaminants we emit and the companies commit to reduction goals. We also have metrics for social issues like health and safety.

Stanford is a forward-looking institution that has the human resources to give us a much more positive reaction like starting research on capturing, disposing and using CO2. The world needs competitive solutions to use its cheapest fuel in an environmentally friendly way. If this is already being done, it would be nice to have it published.

Manuel A. Milan, MS ’73

Chihuahua, Mexico