Two years ago, Cantor Center for the Visual Arts curators invited contemporary painter Darren Waterston to come for a visit. The plan was to have the artist “mine the museum,” searching for objects that inspired him—a set of Albrecht Dürer woodcuts, perhaps, or Yurok baskets. Then he’d go back to his studio in San Francisco and produce artworks for an exhibit that would juxtapose his creations and the original pieces, new with old.

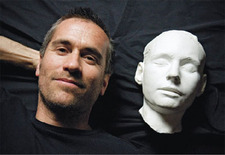

That was the idea, anyway—until Waterston wandered into the Stanford Family Room and saw the white plaster death mask of Leland Stanford Jr., made after the 15-year-old succumbed to typhoid in 1884. “The impression of a youthful face, chalk white, eyes shut, refusing to be forgotten, was deeply compelling to me,” recalls Waterston, 43. “It was very provocative, and I decided this is what I wanted to do my project on.”

The result, running through July 5, is Splendid Grief: Darren Waterston and the Afterlife of Leland Stanford Junior, a curious and moving tribute to the University’s namesake. Part contemporary art exhibit, part History Channel, and part theater, the installation recreates a Victorian mourning parlor. Its centerpiece is a large circular settee similar to one in Stanford family photographs, only this one is topped with a veil of black chiffon that rises to a corona on the ceiling. Fluttering around it are some 3,000 black paper Morpho butterflies symbolizing fleeting life and transition, each hand-painted in iridescent mother-of-pearl.

For the backdrop, Waterston designed an owl-pattern wallpaper inspired by a specimen in Leland Junior’s natural history collection. He painted four large ovals with the otherworldly names of Materialization, Vital Fluids, Ectoplasmic Veil and Flight; a large polyptych called Elegy for Leland (Florentine Sky), plus 20 smaller watercolors inspired by Leland Jr.’s collections and Victorian motifs.

Complementing the new works are seldom-seen paintings culled from the museum’s regular collection—Emile Munier’s 1884 tribute, Leland Stanford Jr. as an Angel Comforting His Grieving Mother, for example. Also appearing are items from the University archives: a letter handwritten in Leland Jr.’s tiny, precise penmanship; a telegram from Jane Stanford to “Mrs. Mark Hopkins” notifying her friend of the boy’s death, and a chalkboard used during a séance.

Waterston comes across as a cheerful, mild-mannered fellow. Yet the subjects of death and transformation are constant themes in his work. Schooled at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in the 1980s, he continued his training in Germany, where he developed an interest in theosophy, early 20th-century European philosophical movements that dealt with spirituality and the afterlife. After moving from Los Angeles to San Francisco, he worked as a volunteer with the city’s Zen Hospice.

Even by the lavish funerary standards of the day, Waterston notes, Leland Jr.’s cross-country funeral train, memorial services and burial were extraordinary. As an 1885 New York Times article breathlessly reported, “the cars and locomotives were almost buried in crepe . . . the floral decorations were of the most gorgeous description,” and the interior of the boy’s prepared tomb was “as magnificent as an Oriental palace,” with walls “covered in purple velvet embossed with gold.”

Waterston thinks the Victorians were onto something. “Today we are so void of ritual; we have such a limited capacity in our culture to deal with death and dying.” As he sees it, “Being present at a death is like being at a birth. To see that moment of transition from both ends is an extraordinary thing.”

Cantor curator Hilarie Faberman first visited Waterston’s studio in 2006. “Art was displayed everywhere,” she recalls. “There were Japanese manga prints and Asian scrolls, plant photographs by Karl Blossfeldt, examples of Victorian hair weaving, prints by the Old Masters,” together with “geological specimens, bits of coral, African ibeji twins, bones, stuffed birds, prosthetic eyeballs and a gothic revival chair.”

Waterston’s art, like his workspace, is a curious blend of the delightful and disturbing. “There’s this kind of attraction/repulsion about it,” Faberman notes. “You’re looking at these incredibly beautiful, luscious-color paintings. But then when you really start looking at the elements, you see that they’re ghastly: ‘Oh, my gosh, there are decapitated heads hanging from those bubbles.’”

Faberman admits that the notion for an exhibit about Leland Stanford Jr.—perhaps the University’s most beloved icon—took some getting used to. Waterston had no previous connection to the University; higher-ups fretted that the installation might be disrespectful. As the artist began collaborating with staff and students around campus, though, his sincerity won converts.

University archivist Maggie Kimball, ’80, helped Waterston locate photographs and other resources for the exhibit. “He brought an artistic sensitivity and intellectual curiosity to his study of Leland Jr. . . . He let Leland Jr. and the study of Jr.’s life and death get under his skin in a way that very few people do.”

Ksenia Galouchko, ’10, was one of about a dozen students who helped create the exhibit’s Victorian mourning wreaths and black paper butterflies, using a long thick brush to paint the butterflies’ wings. “The workshop made me think of my college from a different perspective: not only as a superb academic institution, but also as a memorial to the Stanfords’ son.”

Mike Attie and Melanie Vi Levy, MFA students in documentary film, collaborated with Waterston to produce a short film that is shown at the exhibit’s entrance, giving it historical context. Our Darling Boy is an eerie five-minute journey back through time, with otherworldly music, camera work that seems to float through the Stanfords’ Sacramento mansion, and voice-overs by actors who portray little Leland, his family and friends.

Faberman thinks that in regard to the Splendid Grief exhibit the Stanfords can rest in peace. “This was done with so much love,” she marvels. “It’s very beautiful, it’s very thoughtful and it’s also very emotional. I think it’s one of those, ‘Wow, I’ve never seen anything like this.’ experiences.”

THERESA JOHNSTON, ’83, is a Palo Alto writer and frequent contributor to Stanford.