The little boy who wanted to be a painter grew up to be a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist. But he never lost his fondness for Monet.

“In his last days, Monet was trying to capture the motion of reeds under water, and he died still trying to get that,” author Michael Cunningham says. “To me, that’s the perfect way to end your career—having done a great deal, and still trying to do something new.”

As his own career continues an award-winning climb, Cunningham, ’75, has published his sixth book—the edgiest to date. Specimen Days (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2005) is a triptych of novellas set in 19th-century New York City, contemporary Manhattan, and a post-meltdown NYC where tourists pay for simulated muggings. The tales are infused with automatons spouting Walt Whitman, and they morph from ghost story to thriller to sci-fi yarn, trading chilling images of child terrorists for a quixotic adventure in an all-terrain Winnebago. Says a 4 1/2-foot-tall lizard to her humanoid accomplice: “I threaten, you drive?” Other sections of the book are dotted with exquisite observations: “The evening sky over Broadway was mockingly beautiful, astral winds herding a flock of wispy pink clouds across a field of lavender.”

For the writer whose 1998 novel, The Hours, won both the Pulitzer and the PEN/Faulkner Award for fiction and was adapted into the 2002 film of the same title, pulling off the science fiction section—with characters in blue Astrohair and shimmering mercury suits—was a stretch. Cunningham says that’s the point. “When you’re writing naturalistic fiction, you are at least writing about the observable world—the landscapes and people and houses and cars of the world in which we all live,” he says. “But in science fiction, you’re making all this stuff up and it can feel very silly. You are more nakedly inventing and you feel more exposed.”

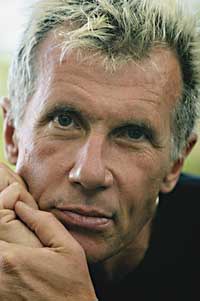

Cunningham says that with a straight face, but a glance at his periwinkle blue toenails and the vestiges of a platinum dye job suggests that he may not shrink from every spotlight. With bare feet propped on the porch railing of a shop in Provincetown, Mass., whiling away a recent afternoon in a wicker rocking chair, the 53-year-old author had a “hi” for every local who passed by. He and his partner, psychoanalyst Ken Corbett, met in P’town and have owned a home in the East End for more than 20 years, dividing their time between the Cape Cod retreat and a home in New York City.

Whether he’s writing at his sixth-floor walk-up in Greenwich Village or in a room without a view in P’town, Cunningham puts in three or four hours every morning. “I go sentence by sentence and just try to get to the bottom of the page, and try not to think about larger questions,” he says. “I need to stand on a fairly solid sentence in order to write the next one, and day by day I feel more like a carpenter, putting up another few shingles.”

Instead of outlining or plotting a story, Cunningham listens, “ready to receive what’s coming.” Part of what he’s trying to do is “open up to something that resides between your unconscious and the magma of the earth, something that is smarter than you are and that can produce something more than your own little ideas about theme and moral and all that.” On productive days, the process flows like a mountain brook. And at other times? “I still force myself to sit there, and I squeeze out one limp, lame little sentence, and always remember that I can take it out the next day.”

The notion that he could aspire to become a writer was birthed in a short-story class Cunningham took with English professor Nancy Packer. “It was that course and she was that teacher that you hope you will have at some point in your education,” he recalls. “Nancy really woke me up to literature. I wasn’t opposed to literature—I liked it just fine—but Nancy talked about the short story from a writer’s point of view, and I think I understood fully, for the first time, that these were not only significant works of art, but that they had been produced by people using ink and paper, which are available right now to anyone who chooses to buy them and start writing things down.”

Cunningham published his first novel, Golden States, in 1984, following with A Home at the End of the World (1990), Flesh and Blood (1995), The Hours (1998) and the nonfictional Land’s End (2002). The critical success of The Hours—his homage to Virginia Woolf, the muse he says is absorbed into his DNA —brought rewards and unexpected challenges. “Up until then, no one had ever called me and said, ‘Do you want to go to Rome and Rio and Paris and Berlin?’” He went, gave talks, was interviewed and came home to publishers offering “daunting amounts of money” for his next book. “Which is a wonderful thing, I’m not complaining about that, but it’s hard to keep ahold of your recklessness.”

And so began Specimen Days, Cunningham’s attempt to do new things with voices and forms. Although he had envisioned the novel before September 11, 2001, the attack on the United States became the centerpiece of the book, the haunting novella titled The Children’s Crusade. “It seemed after 9-11 that a terrorist is to some real extent a child, even though the person in question may be 27 or 35,” he says. “There is some sort of childish simplicity involved, and the capacity to believe in absolute good and absolute evil, and to hold a singular body of belief, is childlike. I just lopped a few years off the ages of my particular bombers.”

When he thinks back on his own childhood, Cunningham remembers himself as “a strange little withdrawn painting-and-drawing child.” He dedicates Specimen Days to his mother, Dorothy, who died before it was published, and says his parents were always “a little uneasy” about his work. “I realized when I started publishing that they had mixed feelings about having produced a child unhappy enough to write novels,” he adds. “If you are an accountant or a doctor, your parents are never confronted with your pain or sorrow, unless you tell them about it. But as a novelist, your parents, if they read your books, see that you haven’t been happy every minute—and who can be?”

But all was far from gloomy for the self-described “surfer stoner dude” in his growing-up days in La Cañada, Calif. After graduating from Stanford, he earned an MFA at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, began publishing short stories and in 1980 landed a fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. There he also met Corbett. “Kenny is the most intelligent person I’ve ever known up close, and he is probably my most important reader,” Cunningham says. “Living with him creates this atmosphere of discrimination and appreciation and a disdain for cheap effects.”

Those are the surroundings he wishes for his students at Brooklyn College, where he has been running the MFA fiction program for the past five years—holding the chair previously occupied by Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. He teaches one course each semester, makes time for his own writing every morning, and still comes up with hours for fun projects—like the Universal Pictures screenplay he’s currently writing, in consultation with actress Julia Roberts, based on Lolly Winston’s novel Good Grief. “When I talked with Universal, I said, ‘I’m not sure if I’m the right writer for this particular book. One of its charms is its sort of jaunty optimism, and jaunty optimism, though I appreciate it, is not exactly what I write.’”

But Universal and Roberts wanted him for the job, so he’s sticking with it. And Scott Rudin, who co-produced The Hours, recently optioned Specimen Days. Cunningham claims he hasn’t gone Hollywood, but there is that hair job (“think Kim Novak in Vertigo”). Turns out it was his answer to a long author tour for Specimen Days.

“I got back at the end of June, after a full month of reading and talking about myself until I was so tired of my grotesquely practiced charms and my gruesomely feigned sincerity that I needed to do something—I needed a change,” Cunningham says. “I thought, ‘Tattoo? Piercing? No, blond.’ So I essentially got in the cab at JFK and said, ‘Take me to my colorist.’ ”

For the sometime painter who one day hopes to write a libretto, and then a Broadway play, it was a statement of sorts. “It turned out that it was a really useful gesture to make, to say to myself, ‘You can do whatever you want. Even if everybody thinks you look ridiculous, it doesn’t matter.’ ”