Dick Grant chose Stanford sight unseen, so he expected a few surprises when he arrived from the East Coast in the fall of 1962. But it hadn’t even occurred to him to check whether Stanford offered the kind of a cappella singing he had fallen in love with at prep school.

Such singing groups were such a ubiquitous part of student life in the East, he couldn’t imagine Stanford would be otherwise. Only after he set foot on the Farm did the extent of his mistake became obvious—he had committed to a campus without a single a cappella group.

“I thought ‘What the hell?’ Coming to college and finding out there wasn’t a group was just appalling,” says Grant, ’66, who’d become a virtual a cappella addict in Bethesda, Maryland.

The gap is almost inconceivable now—a time when freshmen have barely set down their suitcases before they’re wooed by one of Stanford’s 10 a cappella singing groups ranging from the Christian-tinged Testimony to the all-female Southeast Asian fusion of Shakti.

But 50 years ago, long before TV shows like The Sing Off or movies like Pitch Perfect made harmonizing newly hip, a cappella was almost exclusively the tony province of East Coast private schools and colleges, particularly Ivy League schools.

At least he wasn’t alone in his outrage. Dormmate and fellow prep schooler Peary Spaght, ’66, MS ’69, MBA ’72, was equally dismayed. Together they put up posters looking for recruits. That led them to join forces with Hank Adams, ’64, a Yale transfer on the same mission.

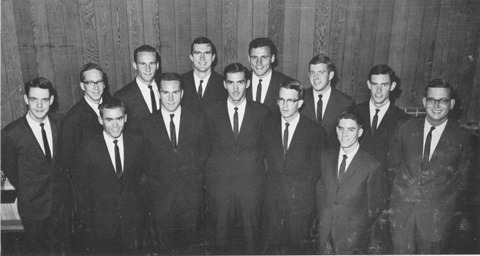

After many hours around the Bowman Alumni House piano, the Mendicants were born. They weren’t just the first student-run a cappella group on campus; they were almost certainly the first at any college between San Diego and Seattle, says Bill Hare, widely considered one of the foremost producers of a cappella music. “They were West Coast pioneers.”

The name choice was basically happenstance. “Mendicant,” or beggar, did conjure images of young students singing for their supper, and the final syllable did offer a play on the Italian word for singing—cantando. But its chief virtue appears to be that it was not something else, such as the Gaelic names like “The Donegals” that Adams favored after a trip to Ireland.

“The Mendicants was sort of the name for which there were the least negatives, therefore it got used,” Grant says.

For their debut, the would-be crooners chose all-female Branner Hall, showing up in blazers, button-ups, slacks and ties, though their audience was apparently still suspicious. “There was a hush in the dining room,” Spaght says. “The girls thought we were going to throw water balloons.”

The details of what ensued are shrouded in myth—or at least the fog of time. Bill Verplank, ’65, recalls the group being prepared to sing only one song, which they performed before making a hasty retreat. Spaght remembers something closer to a five-song set, a memory more in keeping with the Mendicants’ reputation for constant rehearsing.

Either way, they walked out on cloud nine, the unknowing originators of campus tradition. A half-century later, such dormitory serenades are staples of life on the Farm. The Mendicants sing on, never more famously—or in greater demand—than on Valentine’s Day, when the crooners offer a song and a rose for $20.

On October 26th, more than 100 past and present Mendicants will gather at Bing Concert Hall to celebrate 50 years and, naturally, to belt out old favorites. It wouldn’t be a Mendicant reunion without a rendition of “Delia,” the group’s signature tune, first arranged five decades ago by Spaght, a Boston venture capitalist, who will be there Saturday.

“A 50th anniversary, that’s enormous,” he says.

Perhaps the biggest surprise isn’t that the group survived 50 years, but that it made it through the first 10. When the Mendicants formed, the Sixties had yet to hit Stanford. But within five years, the campus has been transformed by long hair, protests and rock ’n’ roll—not the most promising soil for a group of well-scrubbed troubadours in Windsor knots.

“The world was going the other way and we were getting haircuts and dressing nice and wearing neckties and singing what the generation arriving after us would have declared extremely square,” says Grant, founding director of the Pacific Mozart Ensemble. “The Mendicants was kind of swimming against that current.”

Amid that upheaval, the group briefly broke up in 1970. But when Adams, who died in 2001, got wind of it, he summoned the members and told them too much energy had gone into making the group for them to just disband. He got them back together and the show went on, albeit not always in a way that its founders envisioned.

In the ’70s, there weren’t hard and fast rules about what a campus singing group should be, says Doug Archerd, ’75. And if there had been, members probably would have broken them anyway. In his day, the Mendicants wore whatever they wanted, mixed in Grateful Dead songs with old standards, and even sang with instrumental backing, a fact that still makes some founders shudder. The only time Archerd remembers performing in a tie was during a wedding at Memorial Church, he says.

Open-collared or not, the Mendicants had an infectious love for singing, one that spawned the beginnings of the broader Stanford scene. “We enjoyed their tradition and we wanted it for ourselves,” says Linda Chin, ’81, MBA ’87, who co-founded the second a cappella group on campus in 1979, the all-female Counterpoint.

Tim Biglow, ’82, who co-founded Fleet Street, the third campus group to form, says he remembers being awestruck by the Mendicants’ talent. Though Fleet Street had a different vision, wanting more theater and humor in performances, he, too, calls the Mendicants their inspiration. “They were the progenitors.”

In more recent years, the Mendicants have returned to their roots, sporting a look that the group’s forebears would approve: white shirts, khaki slacks and red blazers—a classic look for a classic group. “I wanted to lean into our reputation,” says Gus Horwith, ’10, who initiated the new uniform after a decade in which the group mostly wore baseball shirts.

The current crop of Mendicants is proud of more than being the oldest a cappella group on campus. Earning a red jacket is an accomplishment. More than 70 hopefuls tried out this fall for eight spots, sophomore Myles Keating says. And members take the job seriously, practicing or performing most days of the week. There’s no denying pride in a lineage that goes back generations, he says. “It makes me feel like I’m representing something bigger than just the current group.”

Sam Scott is a senior writer at stanford.