As she sat in the middle seat of a packed plane, Rachael Flatt couldn’t contain her sobs. She had just completed her final professional competition, at the 2014 U.S. Figure Skating Championships, and the seat-back television in front of her flashed a highlight reel from the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. There she sat, face-to-face with the image of herself at the pinnacle of her career, and she broke down. “I’m not a big crier,” says “Reliable Rachael,” the nickname Flatt, ’15, had earned for her consistency on ice. “But it was so overwhelming.”

When her plane landed, the then-junior headed straight to her dorm. Flatt’s roommate, Jasmine Camp, had just returned from women’s basketball practice. “I crawled into Jazzy’s arms and I was like, ‘I don’t know what’s happening!’” Flatt says of facing sadness, relief and a question of identity upon retiring from her sport at 21.

SHE’S STILL GOT IT: Flatt at an ice rink in San Jose. (Video: Aaron Kehoe)

This loss of identity is a familiar feeling for any athlete, but particularly for those who have performed at the world level. “You have to grieve, and no one talks about that at all in the sport,” she says. “No one prepares you for that feeling.” Four years later, Flatt has chosen to channel her energy into creating digital mental-health tools to address athletes’ specific challenges, and sharing her experiences with internet-fueled body shaming to help others feel more secure when it happens to them.

‘It’s like euphoria’

Flatt took her first skating lesson at age 4, but the Del Mar, Calif., native also dabbled in surfing, tennis, dance and gymnastics. When she was 8, her family moved to Colorado for work — her father, Jim, is a biotech executive, and her mother, Jody, is a molecular biologist — and she threw herself into gymnastics and skating. She says she was probably better at gymnastics, but she felt a stronger connection to skating: “For some reason, it resonated more with me.” She soon mastered triple jumps — essential in international competition — and in 2005, she won the U.S. novice national title. “Maybe I should stick with this,” she remembers thinking.

Flatt was drawn to the thrill of competition and the focus required to execute a program. She rarely got nervous, trusting her preparation and training. “At the end of a program, you tune back in, and the audience is going nuts, and it’s the most exciting, rewarding feeling,” she says. “It’s like euphoria.”

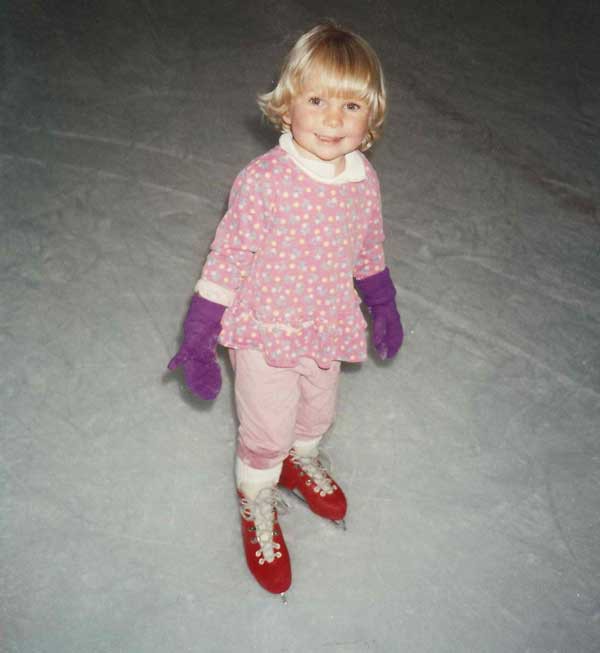

BABY STEPS: Flatt began skating at age 4. (Photo: Courtesy Rachael Flatt)

BABY STEPS: Flatt began skating at age 4. (Photo: Courtesy Rachael Flatt)

Flatt kept an eye on the Olympics, but she also pushed herself hard in school, maintaining a 4.0 GPA while training eight hours a day. “For whatever reason at a young age, I just had this very practical view going into sports,” she says. “You never know if it’s going to work out; you could always get hurt; something could happen that could end your career prematurely.”

Staying focused

“I was known for being very mentally tough and very competitive,” Flatt says. “I always delivered.” Her performances, however, weren’t enough to protect her from cruel social media commenters. “I was teased constantly about my weight and all that stuff. The running joke was ‘Rachael Fat’ instead of ‘Rachael Flatt.’” She knew better than to pay attention to it, but sometimes curiosity won over and she’d scroll through YouTube to read what people wrote. This level of public scrutiny only piled on to the self-esteem and body image issues that any teenager might have.

And it wasn’t limited to anonymous commenters. “I constantly received feedback from judges and coaches about needing to lose weight and to tone up,” Flatt says. “It was very frustrating for me to deal with that, but fortunately it never progressed beyond that.” She credits her support system of parents and friends with helping her maintain a healthy relationship with food. They’d remind her, “OK, you need to be realistic. Take care of your body. Fuel your body.”

‘I was teased constantly about my weight and all that stuff. The running joke was “Rachael Fat” instead of “Rachael Flatt.”’

At 17, Flatt became the U.S. national champion, and she and Mirai Nagasu represented the United States at the 2010 Winter Olympics. In Vancouver, “I had the performance of my life but ended up not getting scored well, as I didn’t receive full credit for two of my highest-scoring jump passes,” she says. “It’s tough to be in those moments, to have the most amazing feeling when I finished my long program at the Olympics, which was probably the best I had ever skated. And then when my scores came back, they were a little low, and I was like, ‘Huh. That’s weird.’” She didn’t know it at the time, but it was the last time she would skate at center ice during an Olympics.

After Vancouver

Flatt deferred her enrollment to Stanford for a year to devote herself to skating. Accustomed to having the equivalent of two full-time jobs, she found having a lighter schedule to be agitating at first — “I didn’t even know what to do with my time” — but ultimately beneficial. She read, watched Project Runway for costume ideas and learned to cook. She competed in the 2011 World Figure Skating Championships on a fractured tibia, managing to finish 12th.

At Stanford, she jumped right into a premed course load, a nine-hour-a-day skating regimen and learning to do laundry. She lost her freshman season to injuries, but continued training as a sophomore in the hopes of having one last healthy competition season. She had to stop in October. “I was to the point where I could hardly walk, my tendinitis was so bad,” she says. “I have a really high pain tolerance, but I couldn’t even put my skates on.”

After another six months off, Flatt vowed to try one last time with the aim of having fun. She trained only as much as her body could handle — about an hour and a half per day — choreographed her own programs and finished 18th at nationals. “Honestly, it was one of the most fun seasons I’ve had,” she says. “I kind of rediscovered my joy for skating.”

With her newfound free time, Flatt dove into student life. She served as junior class president and as a member of the senior class cabinet, danced with Urban Styles, joined the Alpha Phi sorority and applied her cooking skills while living in the Mirrielees apartments (still rooming with Jazzy).

Carving a new path

As a senior, Flatt became a research assistant in the lab of professor emeritus of psychiatry and behavioral sciences C. Barr Taylor. There, she has worked on an evidence-based online screening tool for the National Eating Disorders Association originally developed by Taylor and Denise Wilfley of Washington University in St. Louis, and helped develop a continuing education course for U.S. Figure Skating on healthy body image and eating disorder prevention. Although she submitted her first round of medical school applications as planned, she then had an aha moment: “I can’t not do research.”

‘It started filling that gap from skating. I thought, “I have to do this.”’

So Flatt continues to work in Taylor’s lab (and teaches some skating) while she applies to doctoral programs in psychology. She wants to continue to implement the digital mental-health tools she has helped develop in clinics and tailor those tools for specific populations, particularly athletes. She believes such tools could help athletes struggling with the highs and lows of competition, injuries and media scrutiny in the international spotlight, as well as the often rocky transition to a new reality in retirement.

Flatt says it was a tough decision not to go to med school, but that the psychology path “just resonated” with her the way skating once had. “I don’t know how to explain it, but part of it was that it started filling that gap from skating,” she says. “I thought, ‘I have to do this.’”

Emily Hite, ’07, is the digital media manager for Stanford’s Office of University Communications and a former professional dancer.