Four years ago, on a serene campus in Menlo Park, a group of longtime editors for Sunset Publishing Corporation, whose magazine touted such halcyon coverlines as “Can’t-Miss Pies” and “Other Things to Do in Newport Beach,” huddled together, panic-stricken.

Since 1898, Sunset—publisher of Sunset magazine and more than 800 books—had chronicled life in the West. That history had been preserved for posterity and research, meticulously catalogued in multiple rooms and dozens of file cabinets. Time Inc., Sunset’s owner since 1990, had just told the editors to empty everything into dumpsters. They were moving to Oakland.

‘The Laboratory of Western Living’

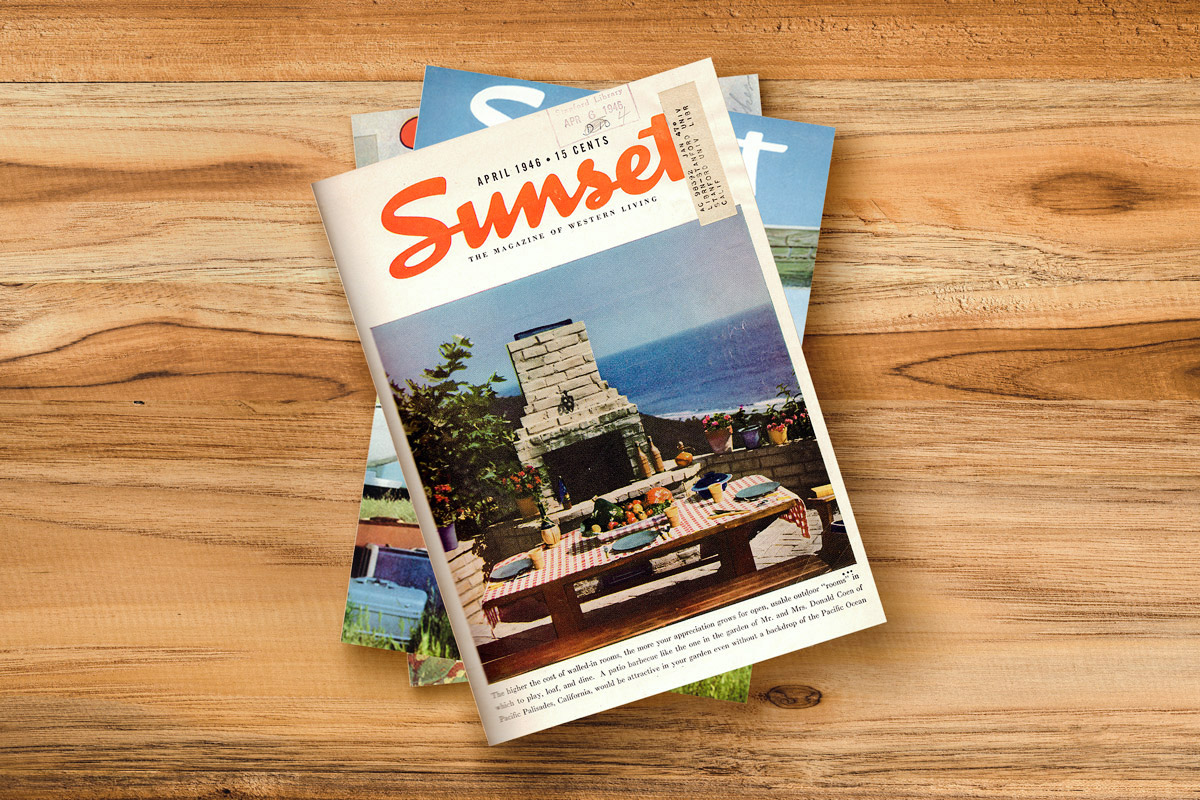

Sunset’s coming of age coincided with the ascendance of California and the West. The magazine was launched and distributed (for a nickel per issue) by Southern Pacific Railroad executives in 1898 to lure travelers westward. (It was named for the Sunset Limited train, which ran from New Orleans to San Francisco.) In 1928, Sunset was bought by Laurence W. Lane. Early issues were literary in tone and included essays by Sinclair Lewis, Jack London and naturalist John Muir, who helped establish Yosemite National Park.

History professor emeritus David M. Kennedy, ’63, a founding co-director of Stanford’s Bill Lane Center for the American West, says that after World War II, the magazine became an emblem of life in the American West, “when the West [became] the most dynamic, booming part of the national economy.” The postwar Sunset cultivated a new and uniquely Western lifestyle that millions aspired to: casual living, enhanced by an appreciation and stewardship of the outdoors.

In 1951, Sunset Publishing moved from San Francisco to a sprawling seven-acre Menlo Park campus designed by the architect Clifford May (father of the California ranch house). With 3,000 square feet of editorial test gardens and sleek test kitchens that cooked up thousands of recipes per year, the campus became known as the “laboratory of Western living.”

Blodgett Canyon, Mont., packing, May 1962. (Photo: Martin Litton)

Blodgett Canyon, Mont., packing, May 1962. (Photo: Martin Litton)

June 1956. (Photo: Ernest Braun)

June 1956. (Photo: Ernest Braun)

‘The List Goes On and On’

Coverage of train travel gave way to car culture. Suburbs boomed. Long before the days of YouTube, the pages of Sunset depicted tree-pruning instructions and kitchen transformations for motivated Western homeowners.

The regional magazine would grow to circulation rates similar to those of today's Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone. “Given the historical circulation numbers and the stories of generations of families who point not only to the specific tips they credit to Sunset but to the importance of the presence of the magazine itself in their homes or mailboxes, Sunset’s influence on strains of Western culture is significant,” says Elizabeth Logan, ’99, associate director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

March 1965. (Photos: Glenn Christiansen)

March 1965. (Photos: Glenn Christiansen)

A 1916 story introduced the garage as a new development in home design. (Fifty years later, Sunset would give tips on converting that garage into an extra room.) A 1961 issue heralds the “catching on” of RVs. The magazine popularized such locally grown produce as asparagus, artichokes and avocados, and regional dishes like cioppino, the improvised fish stew that Italian fishermen created on San Francisco docks. “We established sourdough French bread as the bread of the West, we championed Jack cheese, and we put cilantro on the map. The list goes on and on,” wrote longtime Sunset publisher Bill Lane Jr., ’42, in his 2013 memoir, The Sun Never Sets: Reflections on a Western Life.

March 1982. (Photos: David Stubbs)

March 1982. (Photos: David Stubbs)

The November 1933 cover depicts a Thanksgiving turkey being basted over an outdoor grill. The August 1971 issue featured now-legendary instructions for building an outdoor adobe oven modeled after the mud-brick ovens used in Mediterranean countries that enjoyed a similar climate.

“The pages of the magazine were full of the new: midcentury modernism, leafy suburbs, backyard pools and barbecues, road trips with the station wagon,” wrote Bill Marken, MLA ’12, a former editor in chief of Sunset, who spent a year at the Bill Lane Center for the American West as a visiting scholar researching the magazine’s influence on the West’s postwar boom period.

Exploring by auto, January 1958. (Photo: William Alpin)

Exploring by auto, January 1958. (Photo: William Alpin)

The car kitchen, January 1958. (Photo: Clyde Childress)

The car kitchen, January 1958. (Photo: Clyde Childress)

Those pages also covered threats to the West’s natural resources and sounded the alarm on the dangers of pesticides, drought and wildfires. Sunset editors investigated the destruction caused by the 1961 Bel Air fire, reporting on which houses burned and which didn’t, and advising homeowners how to prepare for future fires. A 1969 story offered alternatives to using DDT in the garden; some pesticide companies were on the list of advertisers the publishers would not accept.

Bel Air fire story, May 1962. (Photos: Los Angeles County Fire Dept.)

Bel Air fire story, May 1962. (Photos: Los Angeles County Fire Dept.)

“Sunset hasn’t just been a mirror reflecting the West—it was an active agent in promoting certain ways of life. The decision to shun advertising from some of these commercial outfits that could have added a lot to Sunset’s bottom line is one indication of just how avant-garde they were and how influential they were in shaping life in the Western region,” says Kennedy. “They were green before people were crystallizing their ideas about this. They had a very forward view of what was environmentally sound and put their money where their mouth was.”

‘We Don’t Have Time to Think About This’

Time Inc. acquired Sunset Publishing in 1990, including the file cabinets containing its meticulously preserved and catalogued archives. There were decades of photographs and negatives—some never used in the magazine—including photos by Ansel Adams and Grand Canyon river guide and environmental activist Martin Litton. There were stories from business publications about Sunset’s remarkable circulation success (at the time of the sale to Time Inc., the magazine had 1.4 million subscribers). And there were books—first editions of more than 800 of them, including The Western Garden Book, first published in 1954 and still considered a gardening bible today, and the 1938 Barbecue Book—possibly the first grilling cookbook ever published, and almost certainly the first to begin with step-by-step instructions for building your own barbecue and outdoor dining table. Russ Parsons, food writer and editor at the Los Angeles Times for more than 25 years, joked that the book’s wooden cover could even be used for kindling in a pinch.

But as print ad sales declined, so did profits, and in 2014, Time Inc. announced that the valuable Menlo Park property had been sold (reportedly to a San Francisco real estate developer for more than $75 million). Sunset staffers had a difficult enough time facing downsizing and relocation from the sylvan campus to a smaller office space in Oakland’s Jack London Square. When they asked Time what would be done to preserve the archive, the answer was heartbreaking: It would become landfill.

“We had architectural photos from the 1960s, an epic story on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, [and] no one on the corporate level seemed to care,” says Peter Fish, MA ’80, a longtime travel writer and editor for Sunset. “I was told repeatedly, ‘We don’t have time to think about this.’ They just didn’t want to deal with anything.”

Fish and his colleagues huddled. The value of the collection was seemingly boundless from a historical perspective. Who could care for it and recognize its worth? Fish called Ben Stone, Stanford Libraries’ curator for American and British history and associate director of the department of special collections. Would Stanford be interested in safeguarding Sunset’s voluminous past?

‘Come and Take Everything. Right Now’

It wasn’t just a magazine’s past that was at risk; a part of the American West’s history could be lost. The potential of Sunset’s archives for research is immense, says Logan. “The magazine provides materials for scholars of 19th-century and early 20th-century mining in the American West, of agriculture in California’s Central Valley, of post-World War II California and the West, and [of] suburbanization.” On a broader level, Logan says, the materials are valuable for historians looking at the evolving image of the region. “How people imagine the American West, how they imagine who belongs here, the aesthetics of the place, the environmental possibilities, what it means to make a home here. You have over a hundred years of data on how that changed over time.”

Stone responded in person to Sunset’s call for help. He had used Sunset materials in special collections courses on the West, and he knew what was at stake. When he went to Sunset’s Menlo Park campus in 2015 to examine the material, what he found—a “treasure trove” of images documenting the history of travel, architecture, environmentalism, lifestyle, food and culture in the American West of the mid-to-late 20th century—exceeded his expectations.

“This fell right into my lap. I knew that Stanford had worked hard on the indexing of the magazine and that this would fit in really well both because of the Lane family collection and the Bill Lane Center for the American West. It’s a significant archive that should be preserved,” he says. “The magazine had taken really good care of it, and the editors were really concerned that it would be lost.”

But the staff’s jubilation was quickly tempered, Fish says, when Time wouldn’t immediately execute an agreement to authorize the transfer. “A great institution wants it. Time doesn’t want it. What’s the problem?” Fish says.

With the clock ticking on the deadline to clear the building, Fish says, the staff made an executive decision. “As Sunset’s staff, we would give the permission they needed. Whatever paper Stanford needed, I signed.” As Fish wrote on Facebook, “We told Stanford to come and take everything. Right now. And they did—not quite in the dead of night, but close.”

‘We Were Doing Something Really Honorable’

Linda Bouchard, then Sunset’s book production manager, prepared 200 boxes’ worth of materials for Stone’s team, including books that had lain untouched since their printing and magazines more than 100 years old.

Bouchard says getting everything safely transferred to the library was one of the most gratifying moments of her career. “I could have kissed Ben Stone’s feet every time he came over and got something,” she says. “We felt like he was saving the history of Sunset.”

Because of Time’s foot-dragging, Bouchard says, “it felt like we were doing something nefarious, although we were doing something really honorable.”

Ultimately, Time authorized the transfer and worked out the necessary details with Stanford. Jessica Yan, then a Time finance director who served as the liaison between the parent company and Sunset, recalls the 2015 move as “a really tough time.” She concurs that Time didn’t express much interest in preserving Sunset’s archive but says that Time entrusted the staff of Sunset to make the best of the move and find a home for these valuable artifacts.

“Time Inc. was gracious to give the archive to us,” Stone says, adding that any drama was due to the timeline for the move and the fact that Time was a big company located 3,000 miles away. “I don’t want to make this a story where Time was the bad guy. I frankly think that this wasn’t very important to them. This was a bunch of old paper that, compared to the building, didn’t have a lot of monetary value.”

‘There Are Many Images That Have Yet to Be Fully Discovered’

Today, four years after the rescue, Time Inc. no longer exists, and most of the Sunset Publishing archive resides on 172 linear feet of shelf space in a climate-controlled facility in Livermore, Calif., overseen by Stanford’s library system. It’s a fitting next chapter in the long story of Stanford’s connection with Sunset, which includes many Stanford alumni among its owners, editors and writers. Editor Charles Field, a graduate of the Pioneer Class of 1895, bought the title in 1914; former university president David Starr Jordan’s writing appeared in the magazine, as did Field’s classmate Herbert Hoover’s. And there were the Lane brothers, Bill and Mel, ’44, who ran Sunset Publishing until 1990. (See sidebar)

African meal story, March 1982. (Photos: Gregg Mancuso)

African meal story, March 1982. (Photos: Gregg Mancuso)

African meal, March 1982.

African meal, March 1982.

In 2017, Sunset was acquired by Regent, a private equity firm. And there’s been another move. After the Regent acquisition and staff reductions, the magazine left its Jack London Square offices. At press time, editors were working from a shared office space in downtown Oakland.

In the meantime, the archive lives on as a vast, rich territory waiting to be explored by historians. “There are many iconic images and many images that have yet to be fully discovered,” says Stone.

“Scholars have had access to the final print version of the magazine for a while, but now we have a chance to look at the margins, at what didn’t go in, and at what else accompanied the material that the magazine was interested in,” says Logan. “What was next to the adobe oven?”

Michael Shapiro is the author of A Sense of Place and the forthcoming The Creative Spark (Fall 2019).