I can’t imagine a more treacherous place than a hospital waiting room. All the weeping and whispering, the sidelong glances and the concealing smiles, and the ineffability of it all bring one to the brink of oblivion. Yet here I sit, an interloper in the kingdom of the sick, struggling to keep my composure.

Since March of last year, the deepest personal connection I have felt was not to a real person but to a literary character: Joseph Grand, from Albert Camus’s The Plague. Does this speak to my complete lack of a social life? Yes. But, at the risk of sounding maudlin, I think (and certainly hope) this bond speaks to more than just my current Zoom-and-gloom lifestyle.

In the plague-stricken town of Oran, Grand is preoccupied with the task of crafting the perfect opening sentence for his novel as miasma consumes the town and his fellow citizens succumb one by one. “How absurd,” I thought this past winter as I struggled to channel Jane Austen for the first line of my Northanger Abbey fan fiction assignment, “that he should concern himself with such frivolous work while people are dying.”

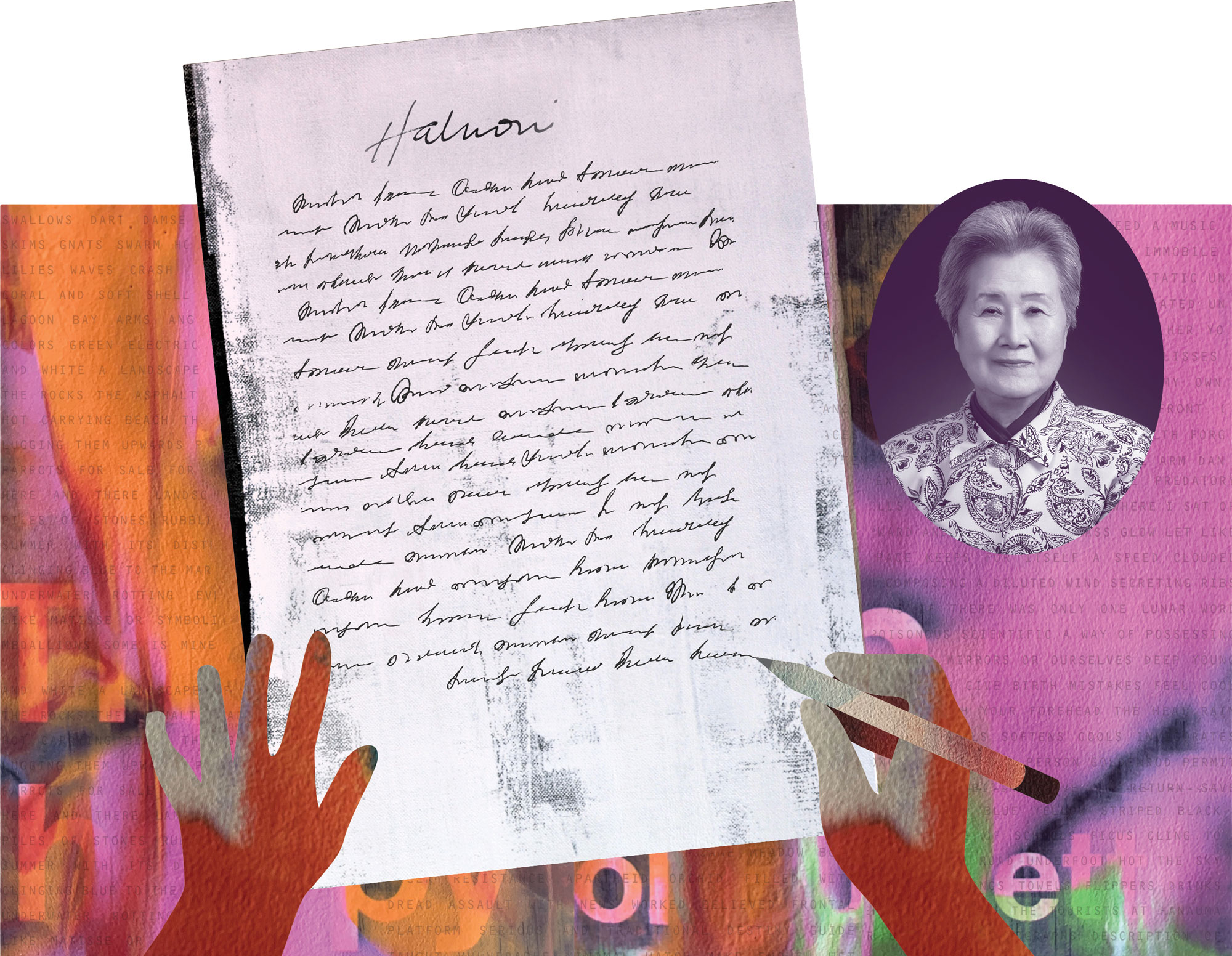

Andrew Tan and his grandmother Ile-hae Cheun. (Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tan, ’22)

Andrew Tan and his grandmother Ile-hae Cheun. (Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tan, ’22)

My situation was surely different, right? I ran down the list of similarities until the list became a mirror and Oscar Wilde’s paradox rang as a taunt in my mind: “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life.” Rebuffing the horned poet on my shoulder, I searched for the distinction that would acquit me of Grand’s escapism, but before I could present my case, I was pulled from my imaginary waiting room into the infirmary, deeper in the recesses of my mind.

There, in an impossibly impersonal photo, sat my halmoni (“grandmother” in Korean) tethered to that ghastly paclitaxel bag, reading serenely from her Bible. Between us spanned a chasm 5,000 miles wide—the distance between Palo Alto and Daegu, South Korea—and on my plateau, I stood, glassy-eyed and unfeeling. Out of the pit rose the Grand specter of guilt to torment me for my numbness. So, I ran.

Days after her diagnosis, I was in Bay City, Ore., an hour and a half west of Portland, where I would spend the next nine weeks of winter quarter. As a lifelong resident of Menlo Park, I had frequently left the Farm to solicit home-cooked meals; this would be the longest I had ever spent away from my childhood home, and I welcomed the change of scenery. With distractions aplenty, from the strange verdure of the environment (“It’s so green!” I texted to family) to the nearby Tillamook Creamery (“The place where they make the cheese!” I reported to my friends), I figured it would be easy to steer my mind away from halmoni, forgetting that I had already enrolled in English 118A: Illness in Literature.

‘Where are the five stages of grief I was promised?’ I screamed into the chasm, feeling that if I could name the emotional void, I would understand it and then know how to bridge the gap.

The weeks proceeded with Chekhov, Sontag, Verghese and, of course, Camus, each text another memento mori that brought me back to the abyss between her hospital bed and my reluctant gaze, between the grief I thought I should feel and the emptiness I truly did. When it came to the anonymous patients of a worldwide pandemic, I could reconcile my public lamentation with, as Camus wrote, “the utter incapacity of every man truly to share in suffering that he cannot see.” But for halmoni, this would not suffice.

“Where are the five stages of grief I was promised?” I screamed into the chasm, feeling that if I could name the emotional void, I would understand it and then know how to bridge the gap. What I did not feel, I could not describe, and what I could not describe, I could not control.

So, I tried to write about her—through gimbap (rice rolls), tteokbokki (spicy stir-fried rice cakes) and Woobang Land (an amusement park in Daegu)—but these efforts only made me feel more distant, especially considering my flair for butchering the Korean language.

Next, I became more abstract, scrawling a poem in my notebook about my desire to “exhume from the grey / matters of the heart,” but predictably, as a means of deflection, my thoughts quickly turned away from halmoni so that soon I was writing about “Purina chow particles / on my cardigan.”

As a last resort, I drafted a note of the things I wished to say to her, hoping to manifest the feelings that I believed halmoni was due:

“Halmoni, I miss you. I miss the way you would peel sagwa [apples] for me without my asking. I miss the way you would smile when I looked at you, even though you could barely speak English and I could hardly speak Korean. I miss your laugh when it would take me five tries to say saehae bog manh-I bad-euseyo [Happy New Year!] before I would receive that prized red envelope. But most of all, I miss shiwonhada [literally, “hits the spot,” aka “massage”]. Saranghae [I love you].”

When I reread the letter, I cannot say that I am flooded with emotion, yet I also can’t say that anything I wrote is untrue. It is an intermediate position, still an eternity away from halmoni but committed to reaching her, nonetheless. Straddling the abyss like the Colossus of Rhodes, I feel afraid, longing to close the rift, but this is better than feeling nothing.

Above the chasm, I continue to write, moving closer with every word. I don’t know if there is enough time for my mind to catch up to my pen, but that will not slow me down. And if, when I arrive, the bed is empty and halmoni is gone, I will know that I wrote as best as I could.

Editorial intern Andrew Tan, ’22, is the grandson of Ile-hae Cheun. Email him at stanford.magazine@stanford.edu.