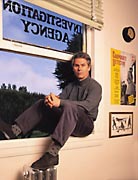

The elevator doors open and he skates out. He isn't wearing a fedora. In crash helmet, knit shirt, chinos and Rollerblades, this is not your father's private eye.

Still, Alex Kline hasn't managed to avoid the trappings of a classic gumshoe. There is an eye painted on the door to his office in San Francisco's North Beach, and inside, a framed photo of Hollywood tough guy Edward G. Robinson glares at a campy poster advertising "Corporate Detective." The final touch: a froufrou lamp with a rose fringed shade. "All of those belong to the guy I sublet the place with," he says as he takes off the blades and slips on his shoes. "They are pretty cool, though."

So is Kline, '80, holder of California Private Investigator License No. 13072.

Kline is a 21st-century sleuth. He probes his share of deaths and disappearances, but he also looks into municipal bond fraud and civil rights violations. His specialties are pretrial research and corporate investigation, which has meant spending a lot of time in courthouses plowing through public records and writing detailed memos. These days, Kline says, "most investigators are more like management consultants than gumshoes. Most of what I do is really pretty tame."

So it's not exactly Humphrey Bogart territory. But Kline has a sidekick Sam Spade never dreamed of: the computer on his uncluttered wooden desk. With its high-speed Internet connection, he can tap into data banks and profile an individual with a few clicks -- work that used to take weeks or months. "The Internet makes 90 percent of 'locates' very easy," he says.

It's not all keystrokes and phone calls, however. "The fun cases," Kline says, "are where you have to tap different resources, talk to people, use your ingenuity."

Feet propped on a radiator and fingers laced behind his head, the married father of two recounts the time he traced a name from a scrap of paper found in a dead man's hand to a flophouse in the Tenderloin district. Once he found a vanished witness by sweet-talking the guy's relatives. "I sat outside their house for the better part of a week," Kline says. "They told me he might not be back, probably because they thought he was in trouble. But I finally told them he was a witness in a case and he was the only one telling the truth." They pointed Kline in the right direction.

Often, getting what you're after depends on how you come across, he's discovered. "You don't want to be threatening, which is why half of the licensed investigators in California are women and why I deliberately use the words 'research service,' not 'investigator,' when I approach people."

Before launching Alex Kline Investigation and Research Service two years ago, Kline worked as an investigator for the San Francisco City Attorney's Office, The Investigative Group in Washington, D.C., and the renowned detective agency Kroll Associates. "He's smart, fun, intellectual, well-educated and eccentric," says David Fechheimer, a prominent San Francisco sleuth. "I've always felt that the people best prepared to be private investigators are former graduate students, who know how to use the library. He also has a balanced family life, which is unusual in the detective business. He's found that it's possible to make a good living doing serious work that's also fun."

Most private detectives come from law enforcement, but Kline took a more scholarly path. Benedictine monks nurtured his talent for solving puzzles at the St. Louis Priory School, where he excelled at translating Latin poetry. "Alex had a piercing intellect, and his wit was always evident, as was his ability to turn a phrase," recalls former classmate Gregory Mohrman, now a monk himself and headmaster of the school.

At Stanford, Kline majored in human biology. He studied law for a year at the University of Colorado-Boulder, then decided to find a different career. "I felt the language of law reversed something I had been working at: clear communication," he says. "In science, you're as good as your results, whereas in law, the sands are always shifting, and you have to bow down to the authority of whoever happens to be on whatever court you're in."

Only one thing about legal work appealed to him: the thrill of the hunt. Kline liked poring over court records and digging through dusty archives in search of evidence. After reading a couple of books about modern-day investigators -- Josiah Thompson's Gumshoe and Patricia Holt's The Bug in the Martini Olive -- he discovered his niche. His hero became San Francisco sleuth Hal Lipset, who gained fame in 1968 by showing a Senate subcommittee how easy it was to stuff a tiny transmitter into a fake olive with a microphone for a pimento and an antenna for a toothpick. "Hal is credited with changing private investigators' work from being glorified process-servers to being almost partners in the litigation process," Kline says. "I enjoy that."

Someday, Kline himself might turn up in a book. About a year ago, Bay Area novelist Kent Harrington, intrigued by the lettering on Kline's second-story window, knocked on the door. Several conversations later, the writer had named a protagonist Kline and was modeling a character on him.

The novel is still in progress. But if ever there's a film version, it could be set entirely on location. Kline -- in real life -- skates five miles to work each day from his home in the Inner Richmond district through Presidio Heights, the Broadway tunnel and Chinatown into North Beach, often singing Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" as he passes the surveillance cameras of the German embassy. Near his office is the art deco apartment where Lauren Bacall stowed a fugitive Bogart in the 1947 noir classic Dark Passage.

It's easy to imagine Kline as the lead in a detective movie; he even has experience as an extra in the 1988 crime-caper comedy A Fish Called Wanda. But the starring role more likely would go to Alex's older brother. "Kevin actually played an investigator once, in The January Man," says the younger Kline. "The character was a quirky guy who was always sipping a cappuccino and was tolerated by the police brass because they knew he was good." At least the actor knew who to call for research.

Diane Manuel covers arts and humanities for Stanford's News Service.