It’s 3 in the morning and the hallway bell rings. It had rung once before, at 1:30, and I knew it would likely ring again. It was going to be a three-bell night. My 100-year-old mom was heading for the bathroom, and that meant I was headed there too.

Until just a few years before, my mom had led a fiercely independent life. And then she got pneumonia. She needed live-in help, and it took me about 10 seconds to decide that that helper would be me. My life was full but flexible. I was a self-employed documentary filmmaker and a part-time NPR radio host in San Francisco, plus I was single. It all seemed pretty straightforward. And so in late 2007, at the age of 59, I moved back to my childhood home in Menlo Park. I moved in with my mom.

In the early days, we managed well. We’d always been close, and we shared dual passions for politics and Stanford sports. Indeed, six months after I moved in, a woman born seven years before suffrage was back at it, making calls to fellow Democrats. “Hello, my name is Adelaide Iverson,” she’d begin. “I’m 96 years old and I want you to vote!” She was an equally unequivocal sports fan. There is nothing quite like attending a football game with a near-centenarian who keeps yelling, “Tackle ’em! Get that guy!”

I had part-time caregiving help during the day, and my companion, Lynn, came down from Berkeley one night a week. Her presence provided some normalcy and inspired me to upgrade from the twin bed I’d had when I was 12. But gradually, of course, my mom became needier. I learned to adjust, and adjust again. I learned that solutions work until they don’t. And then a urinary tract infection landed my mom back in the hospital and then into a residential nursing care facility. And that is when two remarkable women entered my life.

At the care facility, a nursing assistant named Eileen Khan was assigned to take care of my mom, though “assigned” is a bit of a misnomer. In reality, Eileen was the only one brave enough to deal with a bedridden but by no means docile Adelaide Iverson.

FARM FAN: Adelaide Iverson at 99. (Photo: Reesa Tansey)

FARM FAN: Adelaide Iverson at 99. (Photo: Reesa Tansey)

Eileen is from Fiji originally, and because of the high cost of Bay Area housing, she lived over two hours away. Later I would learn that she usually only made it home to see her three school-age kids on the weekend, spending weeknights on the floor of her parents’ apartment. I knew I would need more help when we got my mom back home, so I asked Eileen if she’d be interested in an extra part-time job. She was. But I also knew that Eileen’s assistance wouldn’t be enough. Fifteen years earlier, during my dad’s final years with Parkinson’s disease, my mom had shown me what lasting love, and lasting care, entail. And I knew I wasn’t my mom. I knew I needed more help.

And it was my mom who provided the solution. She was a loyal friend, visiting her surviving chums well into her 90s. One of her friends had a wonderful caregiver named Sinai Latu, a native of Tonga. That friend had recently passed away, so I called Sinai. She’d already secured another position, but my mom had left an impression on her. “Adelaide’s visits were sometimes the only break I’d get,” she told me. “If she needs help, I want to help.”

My mom turned 98, then 99, and our care needs continued to inch upward. But I had partners now. When my mom reached the point where she needed a hospital bed, I grimaced at the thought of moving all that bedroom furniture. Late one night, the doorbell rang. It was Eileen’s 17-year-old son and four of his pals. When I asked Eileen later how she cajoled five teenagers into driving 70 miles at 11 o’clock at night to move furniture, she said, “Because you and Adelaide are family now, and I’m the mom.”

Sinai’s presence was softer but no less impactful. She’d arrive with flowers every week. She got Adelaide to Sunday Mass at MemChu without fail. And she was rarely fazed when my mom was demanding or difficult.

My mom reached 100, and we held a party with over 100 guests in Team Adelaide T-shirts. She was pleased to get a letter from President Obama, happier still to get congratulatory notes from the Stanford football, basketball and baseball coaches.

But I was starting to find that even though I now had more help, getting respite didn’t mean getting recharged. Eileen and Sinai had given me a lifeline, but I couldn’t see how I’d ever become untethered.

Eileen and Sinai accepted my mom’s growing limitations with grace, while I sometimes stomped around the house, slamming doors like an angry teenager.

And then the three-bell nights began. I’d installed a bell by my mom’s bedside that she could ring when she needed to go to the bathroom, but it began to feel like I was going to bed with an alarm that was destined to go off at random intervals. I was always short on sleep and soon short on temper as well.

As my mom crossed into her 100th year, her mental abilities finally began to falter. I could see it, and it turned out she could see it too. Early one morning, she looked up at me and said, “I think there are two Adelaides. There’s the good Adelaide, who’s smart and pretty and knows things. And there’s the bad Adelaide, who’s ugly and stupid and doesn’t know anything. I’m not sure which one is here right now. But I think it’s the bad Adelaide.”

It felt like a turning point, except I was beginning to understand that there aren’t any turning points. There are only commas. My mom turned 101 and then 102. I turned 65 and then 66. At an age when you’d like to think you know who you are, I began to discover darker corners of my personality. Eileen and Sinai accepted my mom’s growing limitations with grace, while I sometimes stomped around the house, slamming doors like an angry teenager. Once, when my evident frustration brought my mom to tears, my only response was to say, “Fine, go ahead and cry.”

PARTNERS: Khan and Latu at Iverson’s wedding in 2016. (Photo: Jan Knecht)

PARTNERS: Khan and Latu at Iverson’s wedding in 2016. (Photo: Jan Knecht)

My best friend, Gary, had once said to me, “You know, it’s not that you’re doing anything unusual. It’s just that it’s unusual for a white guy.” And so here I was, a white guy whose life had been blessed by opportunity and open doors from the moment I was born, now in over my head. Eileen and Sinai, on the other hand, were women who’d arrived in America with nothing save skill, determination and a deep cultural understanding that caring for the old is part of life’s bargain.

I told Eileen and Sinai that I didn’t think I could keep doing what I was doing. So they took charge, taking over both nights and weekends. And in doing so, they rescued me. I slept. I saw Lynn more. I began to feel less like a caregiver and more like a son.

Eileen and Sinai draw their compassion in part from deep religious faith. Late one evening, I found Eileen wrapped in her prayer shawl, fingering her beads as she whispered a Muslim prayer for my mom, a lifelong Catholic. The next morning I told her how moved I was by what I’d seen. She smiled and said, “Well, you know, Sinai taught me the Lord’s Prayer, so I say that sometimes too.”

Today my mom is 105 years old, and I no longer live with her. At age 68, I got married, a gift I owe not only to Lynn, but to Sinai and Eileen. They are somewhere between sisters and daughters to me, joined together in kinship by the diminished but undaunted spirit that is Adelaide Iverson.

And I realize now that my mom was right: There are two Adelaides. But while she had always defined the good Adelaide by the power of her personality and the liveliness of her mind, I see another Adelaide now, one who’s defined by a wondrous interconnecting force that melds her remarkable will with mutual bonds of affection.

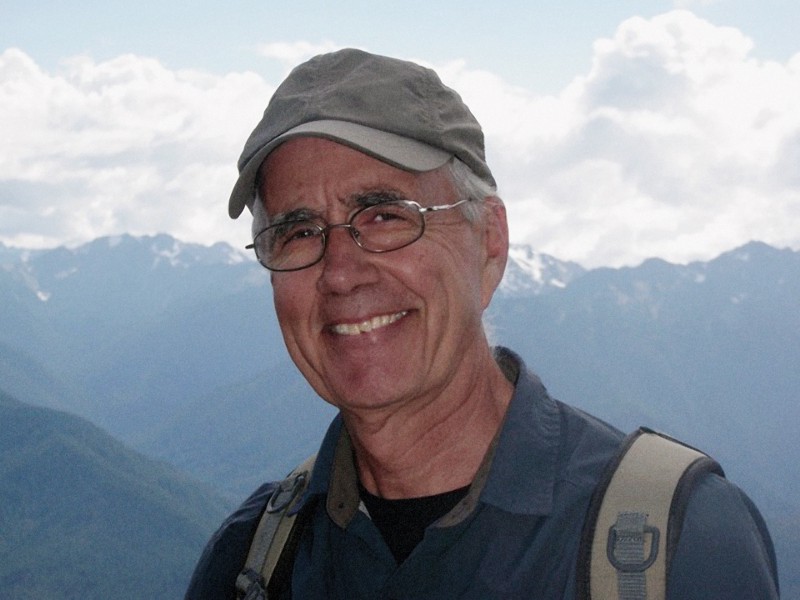

HERE COMES THE SON: It took Iverson “about 10 seconds” to decide to become his mother’s caregiver. (Photo: Dave Iverson)

HERE COMES THE SON: It took Iverson “about 10 seconds” to decide to become his mother’s caregiver. (Photo: Dave Iverson)

One evening right before Christmas last year, I sat with my mom, just holding hands, and I felt a wave of tenderness that in recent months had often gone missing. After a while, she looked at me and said, “I feel lucky.” She said it more clearly than anything she’d said in a long time. And so I said, “Well, I feel lucky too.” I told her that I felt lucky for all that she’d added to my life. And then she said again, “I feel lucky.” I asked her if she could tell me why. There was a long pause, and then she looked at me with eyes as bright as winter stars and said, “Because there is love all around.”

When illness and aging enter our lives, it’s often hard to feel that love is all around or even that love is around at all. But I am learning that even in difficult times, perhaps especially in difficult times, unexpected love can still be found. For me, that precious gift came from two people who came to this country seeking a better life and made my life, and my mom’s, infinitely richer in return.

Dave Iverson, '71, is a writer and a radio and television producer in Oakland.