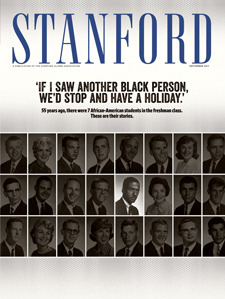

The ’62 Seven

Readers responded to “What It Was Like to Be an African-American Freshman in 1962” (September), about the experiences of a relatively large cohort of African-American freshmen in 1962.

I was jarred all over again, 55 years later, by your story on the seven African-American students admitted in 1962. That was my freshman year, too, and having come from a reasonably if not perfectly integrated Chicago private high school, I had assumed there would be many more African-American students than there turned out to be. Seven?!?

Thanks for reminding us of how things were, and to some extent still are.

Alan Heineman, ’66

San Francisco, California

What a great group of people. However, if they are the vanguard, what of those of us who came before? Are we the scouts?

Handsel B. Minyard, ’64

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

I enjoyed the interviews of the African-Americans who were freshmen in 1962. But I found the article gave the misleading impression that there were few, if any, black students around before that time. On the contrary, African students were there. They are as entitled to “vanguard” status as those you featured, for they enjoyed and indeed suffered similar experiences.

William Kinsolving, ’59

Lakeville, Connecticut

The Stanford cover headline on the seven of 1962 is, “If I saw another black person, we’d stop and have a holiday.” To me in 1953 and to me in 2017, that is an alien sentiment.

I was one of only two African-Americans entering as freshmen in 1953. The other was Jean McCarter. Upperclassmen threw Jean and me together for an Orientation Week dance. I found Jean to be interesting but felt no compulsion to seek her out or hang with her just because she was African-American.

I pursued my interests and had a great time doing so. For example, I was music director of the freshman talent show. Admitted to Stanford as an electrical engineer, I became a music major. I was the principal composer for Big Game Gaieties of 1955—“Best music heard in years,” headlined the Stanford Daily review of the show. I’ve spent most of my adult life as a composer and a musicologist.

At Stanford I dated white girls because they crossed my paths and attracted me as I pursued my interests.

In one of the very few times in which my race was brought up to me at Stanford, an upperclassman in charge of Toyon Hall asked me if I minded dating white girls. I said no and that was that.

Stanford’s increase of African-American students due to efforts at “diversity,” the increase of African-American faculty due to demands of African-American students, the establishment of a Black Student Union, and so on along those lines, are to me steps backward for Stanford. I see them as regrettable balkanization of the Stanford family.

My most excellent African-American parents encouraged me to be an individual. That is what I am, most decidedly. All due praise to the awe-inspiring fighters for black civil rights in the United States, but I have never been of that tribe.

On balance, I am not in sympathy with the Stanford article on the seven of 1962. I thank my lucky stars that I entered Stanford as a freshman in 1953.

Jim Anderson, ’57

Palo Alto, California

I don’t remember his last name. His first was Russell. His room was a few doors down the hall from mine in Junipero, Wilbur Hall. It was our freshman year, 1960.

During spring quarter, many of us participated in Rush Week. There was one fraternity house in particular I was interested in. I was invited into that house the first night, and returned to the dorm excited, my self-doubt decreased a little and my self-esteem boosted a few notches.

As I returned to the dorm, I passed Russell’s room. He was sitting on his bed, tears in his eyes. I stuck my head in and asked if he was OK. I sat on the bed next to him as he recounted his deep disappointment and sadness about not being invited into the house his best friends were going to pledge. Why? Because he was black.

A couple of days later I saw Russell and asked for an update, and how he was. I also told him that I didn’t pledge my first choice. Why? Because they wouldn’t pledge my best friend. Why? Because he was Jewish.

Russell did eventually join a fraternity house.

Terry Tillman, ’64

Ojai, California

Can the Left ever get past its obsession with color, particular if the color is black? If color or race really mattered (most Americans have moved on), then how do you explain the fact that there are successful people of all colors and races (why, even black people!) in every profession and line of work? The fact of the matter is, if you pay attention in school (instead of horsing around) and work hard, you can, and will, succeed. For the most part, there is no one my age or younger, except those born with a significant disability, who has not had tremendous opportunities in this country. Some people throw those opportunities away because of drugs, violence or any number of reasons. But that’s their problem, not mine. Unless they enter my home uninvited, in which case I’ll take care of it.

Let’s start looking at people for what they do instead of their color.

William Brennan Lynch, ’77

Santa Barbara, California

I was president of Fremont House in 1964-65, and so when Roger Clay, ’66, said that “it was like our own fraternity,” it brought back fond memories. It makes me a bit sad, however, that I wasn’t attuned to his sense of isolation in our larger Stanford community, and that at the end of his time at Stanford, he said, he “just wanted to get out.”

I remember Roger Clay as a warm, outgoing and studious person who inspired me to be a more committed and serious student. My congratulations to Roger on a life well lived, and to Stanford for recognizing what special talents he continues to bring to the Stanford family.

James D. Blaschke, ’67, MA ’68

Gilroy, California

In fall 1947, when I was an undergraduate living in Cubberley House, I stopped off at the Union for a cup of coffee. Soon, I was chatting with a young man who told me he had been accepted at Stanford Law School by sending in a photo of a white man with his application. The young man was black.

He invited me to dinner to meet his wife. I was delighted.

The next day at lunch, I told my housemates about my dinner and that I wanted to reciprocate by inviting the young couple to Cubberley for dinner. The reaction was so negative, I did not reciprocate. I told myself I did not want to make a social experiment out of a nice and vulnerable young couple. But was

I just being a coward? A hypocrite?

How far have we come from 1947? How far do we still have to go?

Evelyn Konrad, ’49, MA ’49

Southampton, New York

Legal Leader

“The Moral Force of Deborah Rhode” (September) profiled Stanford law professor Deborah Rhode.

Kudos to Professor Rhode for her incredible work documenting issues such as the acceptance of cheating in society, bias in favor of beauty, ethical challenges people often face—and overall striving to create a fairer society!

Michael Mackaplow, MS ’91, PhD ’96

Chicago, Illinois

I enjoyed the article about Deborah Rhode and hope my daughters will read it. But there was one moment that brought a chuckle. Rhode is quoted about a dispute with Judge Alex Kozinski:

“He appears to have a sense of entitlement and to feel an insularity from accountability.”

He’s a federal judge. He’s immune from civil suit, has a constitutionally protected life term and can’t be fired. He gets paid over $200K no matter how well he does his job.

So he is entitled and insulated from accountability. It’s not just a sense or feeling.

Warren Redlich, ’92

Boca Raton, Florida

History Lessons

In “Re: The Thought Police” (September), education professor Eamonn Callan argued that Stanford must remain an “intellectually unsafe space,” but also that it should mitigate social stigma for students.

Eamonn Callan begins with a laudable defense of freedom of speech at Stanford while acknowledging its potential to ruffle some feelings. Yet Callan abandons this posture of candor at the end of his article in praising the removal of photographs of past distinguished professors from the walls of the School of Education because, he claims, the “whiteness” of those portraits might alienate Stanford’s minority students.

Isn’t the revelation and pursuit of truth, even objectionable truth, what a university ought to be about? Callan argues that “small changes can also move us incrementally in the right direction.” But is it moving things in the right direction to shield Stanford students from the truth about Stanford’s past, when open knowledge of that past ought surely to motivate them toward forging a future of different complexion?

Kenneth G. Everett, PhD ’68

DeLand, Florida

As I began reading Eamonn Callan’s piece about “safe spaces,” I was pleasantly surprised.

Then I reached the part where he celebrated the removal of the School of Education photos of past and present faculty.

No cigar.

History is like a window to the past, giving us the chance to not only learn, but to trigger thought.

My Stanford Quad yearbooks show virtually all white faces. When I see those photos from my perspective of today, questions come up. Why? Who? What about other schools? How far have we come?

Let’s not rewrite history.

Bob Olson, ’60

San Ramon, California

I find the removal of the photographs solely because most of the people shown in them are white to be absurd, and I suspect Callan’s remarks and the school’s action are the kinds of things that help to explain the success of the Trump campaign. Shame on everyone involved in removing the photos or praising that decision.

John M. Gates, ’59, MA ’60

Wooster, Ohio

Like a Flash

The eco-tips column “Carbon and the Cloud” (May/June) compared the carbon footprint of cloud storage with that of storing data on a hard drive.

The answer made no mention of the use of flash memory in the cloud, which has become very prevalent, and which is increasing dramatically over time. Flash uses much less power than a hard drive. While its cost is somewhat higher per bit, the total cost of ownership of flash has been less than that of a hard disk for nearly five years now. This is an important advance in reducing the power used to store the world’s data. The exclusion of any mention of flash in this response was a dramatic oversight, as flash’s importance in the world is nothing new: Many laptops use flash (as solid-state drives) instead of hard drives, and mobile computing today relies solely on flash.

Brian Berg, ’78

Saratoga, California

The following did not appear in the print version of Stanford.

On “What It Was Like to Be an African-American Freshman in 1962” (September).

Your article brought back memories of my 1956 senior year. I had grown up in a Midwestern city where blacks were unwelcome and segregated, and I matriculated at an all-white boarding school. There were only a few black students in my class at Stanford. Nonetheless, as I remember, three or four of us formed a pseudo-NAACP chapter whose purpose was to scout the local shops and restaurants looking for racial discrimination. We felt it a just cause. In retrospect, how little did I know about racial injustice.

Richard R. Babb, ’56, MD ’60

Portola Valley, California

As a sophomore in 1954, I moved into Alpha Tau Omega and saw pledging in action. When we were considering inviting a black brother, the Dean’s Office allegedly advised the house not to do that, so he was “blackballed,” as the process was called(!).

The next year, after writing home about how much fun I had jitterbugging with fellow Sponsor Jeanie McCarter, I received a letter back from my mother telling me that “God didn’t intend to have the races mix.” (I believe she would have welcomed my daughter’s black husband had she lived to 102.)

In 1956, I sent a letter to the Daily commenting that while parts of the South were beginning to integrate, Stanford’s fraternities remained segregated. The night my letter was published, a cross was burned on ATO’s front lawn.

The good news, of course, is that Stanford’s subsequent “path toward pluralism” and breaking down of impediments to enrolling the best of all applicants has traveled upward and aspires to even greater relevance in today’s world.

Jim Lauer, ’57, MD ’65

Grand Junction, Colorado

I had to open up the September issue. There on the cover was the picture of a classmate that everyone in the Class of ‘66 knows by name: Ira Hall.

Ira spoke eloquently in his portion of the article on the experience of early African-American undergraduate students on campus. I had no idea that he was one of only seven in our class [of about 1,400]. I can only imagine how isolating that must have felt. I had attended an “integrated” high school in the suburban St. Louis area and got out my yearbook for a comparison, and sure enough, there are only 12 pictures of black students in a graduating class of 400.

During my three years of living in the Theta Chi house, we went through the same experience that Alexander Lewis mentions in his portion of the article. The house pledged its first black member and soon after had a visit from a regional field secretary of the national fraternity that tried to “explain” to our house that although they had removed the “whites only” language from the national charter, blacks were not welcome. We treated him at a dinner in the house to a fake birthday tradition of flipping over a table, and he ended up with the contents in his lap. We didn’t see him again during my time there.

These were small first steps to be sure in our nation’s search for better race relations, but steps nevertheless. I, for one, am thankful for the efforts at Stanford to be more inclusive. A heartfelt thank you goes out to Sandra Drake, Paul Rose, Ira Hall, Alex Lewis and Roger Clay for their willingness to be among the first responders to cross the color line at Stanford and for sharing their Stanford stories with the rest of us.

Edward Strode Weaver, ’66

Leavenworth, Washington

In my freshman year (’53-’54) there was one black student in Encina. Some individuals on the second floor thought he was “uppity” and, so they claimed, stuck his head in a toilet and flushed it. Whether true or just boasting, it says a lot about racial attitudes in the early ’50s. On the third floor, there was a Navajo boy who felt isolated, lonely and homesick; he was soon gone. I did an MA year in ’57-’58; there was one black student in my cohort, with whom I frequently studied. He ran out of money and did not finish the year. Although one of our professors proudly exhibited his NAACP membership certificate, it occurred to no one to offer assistance.

Having spent my professional career in universities, I am well aware that administrations always are eager to pump up their minority enrollment statistics, but seldom willing to fund the support systems many minority students need.

Raymond Waddington, ’57

Davis, California

On “To Change People’s Minds” (July/August) and Letters to the Editor (September).

As an alumna of Stanford, I was appalled to see your interview lionizing Ayaan Hirsi Ali as a feminist and hero.

She has no credentials or education in Islam, Islamic studies or Islamic law. She has been discredited by academics in the fields of Islam and Islamic studies not because of “political correctness,” but because she defames Muslims, spreads utterly false statements about Islam and Muslims, and fabricates statistics as well as generalizations.

She has suggested that the U.S. Constitution be amended to not protect Muslims, and she has urged a war with all of Islam, not just “radical Islam.” Her story—so adoringly portrayed in your article—has been disproved. She was convicted of perjury in the Netherlands.

She throws around terms of art to give herself credibility and with absolutely no understanding of them. She has no idea what sharia means (loosely, it just means “Islam”), though she uses it to mean some sort of medieval rigid philosophy that will be imposed on Muslims and non-Muslims alike, which has historically not been the case. Her statements are frequently false or fabricated, and she has been repeatedly discredited by individual academics as well as universities.

According to the Bridge Initiative, in the United States, in 2015, there was an attack on Muslims every 48 hours. Yet Hirsi Ali says there is no Islamophobia. Perhaps we should call it anti-Muslim prejudice, then. Because whatever you call it, it is certainly supported by facts, something Hirsi Ali is only tangentially acquainted with.

Since the war on terror began, the United States has killed up to 2 million Muslim civilians, according to a Physicians for Responsibility study. In the same period, Muslims have killed 94 Americans, according to the New America Foundation. Yet Hirsi Ali consistently portrays the United States as the victim of Muslim terror.

In your interview, she says ISIS follows the letter of Islamic law, when, in fact, virtually all Islamic scholars worldwide have condemned ISIS as violating countless rules of Islam. From the very beginning of Islam, in the 7th century, terrorism has been severely punished, and the Islamic rules of warfare are more stringent than modern international rules of warfare. Hirsi Ali’s statement is just another falsehood.

Far from being a hero, she is terrible for Muslim women. She insists that honor killings and female genital mutilation are Muslim practices, even though, for example, in Africa they are practiced by as many Christians as Muslims. She portrays Muslim women as required to walk behind their husbands, which is just not true; why does she never mention the 11 Muslim women who are or have been heads of state (presidents or prime ministers) of Muslim countries in the past few decades (not even counting the historical queens and rules of Muslim lands)?

Would your magazine publish an interview with a known anti-Semite with no qualifications or education in Judaism? Or one of the Charlottesville white supremacists? Ayaan Hirsi Ali is the equivalent. As a Stanford alumna and an academic in Islam and Islamic law, I am devastated and shocked that you would give this woman, her defamatory statements and her bigotry a voice; by doing so, you’re helping her spread misinformation and prejudice.

Sumbul Ali-Karamali, ’85

Mountain View, California

It’s sad that Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s Stanford interview should elicit such irrational responses from among the highly educated Stanford community. I searched the article and online sources for the slightest shred of evidence to support comments characterizing her as an “Islamophobic bigot . . . propounding virulent anti-Islamic hate speech” or someone operating as part of a “globally orchestrated campaign,” someone who “condemns an entire world religion.” I looked in vain for evidence to support the claim that she vilified Islam and all Muslims, or attempted to legitimize or spread xenophobic anti-Islam or anti-Muslim sentiments. (I also struggled with the logic of regarding an immigrant with a truly cosmopolitan background as xenophobic, and was perplexed at the attempt to equate her ideas with those of Holocaust deniers and white supremacists, and with the implication that she had called Islam “a gutter religion of infidels.”)

All these ad hominem attacks and far-fetched analogies were presented without a single citation or other evidence to support them.

Like Martin Luther, she is attacked and condemned for daring to suggest that religious reform is needed. She is excoriated for pointing out the rather obvious fact that there is a political component to Islam that has become radicalized and, yes, indulges in some rather spectacular acts of violence against Muslims. Boko Haram and ISIS come to mind, but of course there are others.

If we are to talk of global conspiracies, who benefits from assaults on a woman who espouses reform?

David Rearwin, PhD ’73

San Diego, California