For people with spinal cord injuries or diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, the computer-driven world looks hopeful. That’s partly because neuroscientists and electrical engineers are making headway on a big task: writing software that can “read out” the brain.

A team led by Stanford electrical engineering professor Krishna Shenoy recently decoded an important piece of that challenge when, by observing the interplay between neurons in monkeys’ brains, they discovered the rules that guide arm movements.

“By leveraging those rules, we’re able to do a better job at estimating how you want to move your arm or a computer cursor each moment in time,” Shenoy says.

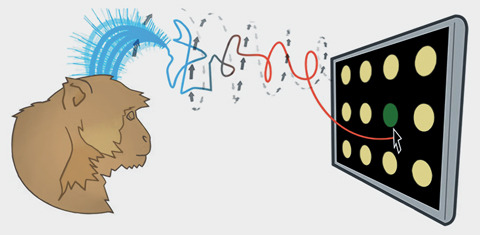

The patterns they mapped enabled the scientists to write better algorithms into the software that guides brain-controlled prosthetics—in this case, a system in which electrodes connect to neurons in the brain and translate the readings to the movement of a cursor on a computer screen.

Photo: Craig Lee

Photo: Craig LeeThe main improvement came with precision. A monkey trained to choose targets on a simplified keypad averaged 29 correct finger taps in 30 seconds. The improved software, translating the monkey’s brain activity as it sought to hit the targets, scored 26 taps in 30 seconds. The most precise alternative prosthetic that the team tested notched 23 correct taps.

The next step is to translate the work to human subjects. The team received FDA approval to do so in 2011 and is currently running clinical trials on two patients with paralysis, using a variety of brain-controlled devices.