There was a time when public high schools offered shop classes in printing, sheet metal and woodworking. For Bob Eustis, who was fascinated as a kid by how things work, that early applied training nurtured an interest in building and in mechanical engineering, and fueled his late-life passion for high-end furniture design.

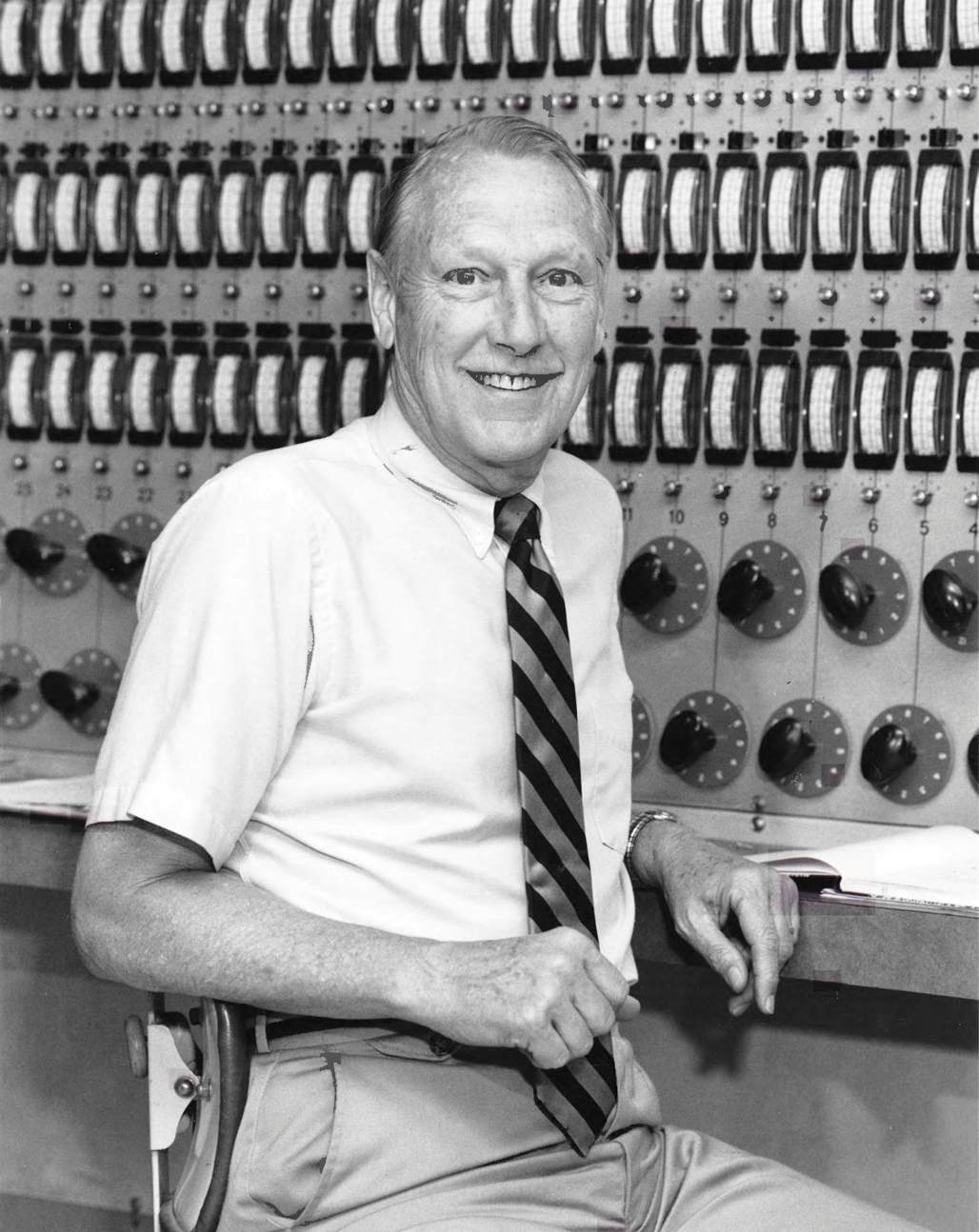

Robert H. Eustis, the Clarence and Patricia Woodard Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Emeritus, and a co-founder of Stanford’s High Temperature Gasdynamics Laboratory, was born in Minneapolis. He died on May 24 at his home on the Stanford campus—a home he’d helped design with his wife, Kay. He was 98.

“Dad used to say that Stanford University in the 1950s wasn’t anything special” — that it lacked the reputation it has now, says his daughter, Karen Vik Eustis, ’80. “He was part of the cohort that changed it all.” With mechanical engineering degrees from the University of Minnesota and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he moved to California in 1954 to work at what’s now SRI International. Stanford hired him to teach thermodynamics that same year. Less than a decade later, Eustis was director of the Gasdynamics Lab, a post he held for 19 years. His research involved the efficient use of fuels and the science of magneto hydrodynamics.

Eustis’s work with students—which won him a Tau Beta Pi award for distinguished undergraduate teaching—helped more than 300 earn their doctorates. Among them was Michael Erbes, ’80, MS ’82, PhD ’87, a principal with R.F. Bell, MS ’90, at Menlo Park’s Enginomix, a company Erbes says was based on his thesis work. At a celebration of life for Eustis in July, Erbes explained that he and Bell, a computer scientist, owe their business, which makes applied thermodynamic software, in part to their mentor, who brought the two together. “We are engineers building on everything Bob started us on,” Erbes said. “Even in the early ’80s, Bob recognized the world was heading toward computer modeling,” and he somehow obtained a computer for Erbes’s and another student’s thesis work. “He wanted students to be able to use software with graphics to see thermodynamic change in real time.”

Forced to retire at age 70 under a now-defunct Stanford policy, Eustis turned to woodcraft. In his garage, he invented and patented a nearly unbreakable furniture joint using concealed steel rods and advanced adhesives. Erbes said part of Eustis’s motivation was to provide jobs for low-income residents of East Palo Alto, where he established a small factory to make hardwood chairs. He later gave the company, Eustis Designs, to the university to endow the Robert and Katherine Eustis Graduate Fellowship Fund. Stanford in turn licensed the intellectual property to a New England chair manufacturer, which reported in 2018 that 30,000 chairs had been sold using the patented joint.

After Kay died in 2003, Eustis found a loving companion in Phyllis Willits, the widow of a longtime friend. He is survived by Phyllis; his daughter, Karen; son, Jeffrey; two grandsons; two great-grandchildren; and his sister.

John Roemer is a freelance writer based in Sausalito, Calif.