Editor's Note: This story was originally published on January 24, 2017.

NO MATTER WHAT MEDIA STREAM you depend on for news, you know that news has changed in the past few years. There’s a lot more of it, and it’s getting harder to tell what’s true, what’s biased, and what may be outright deceptive. While the bastions of journalism still employ editors and fact-checkers to screen information for you, if you’re getting your news and assessing information from less venerable sources, it’s up to you to determine what’s credible.

“We are talking about the basic duties of informed citizenship,” says Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education.

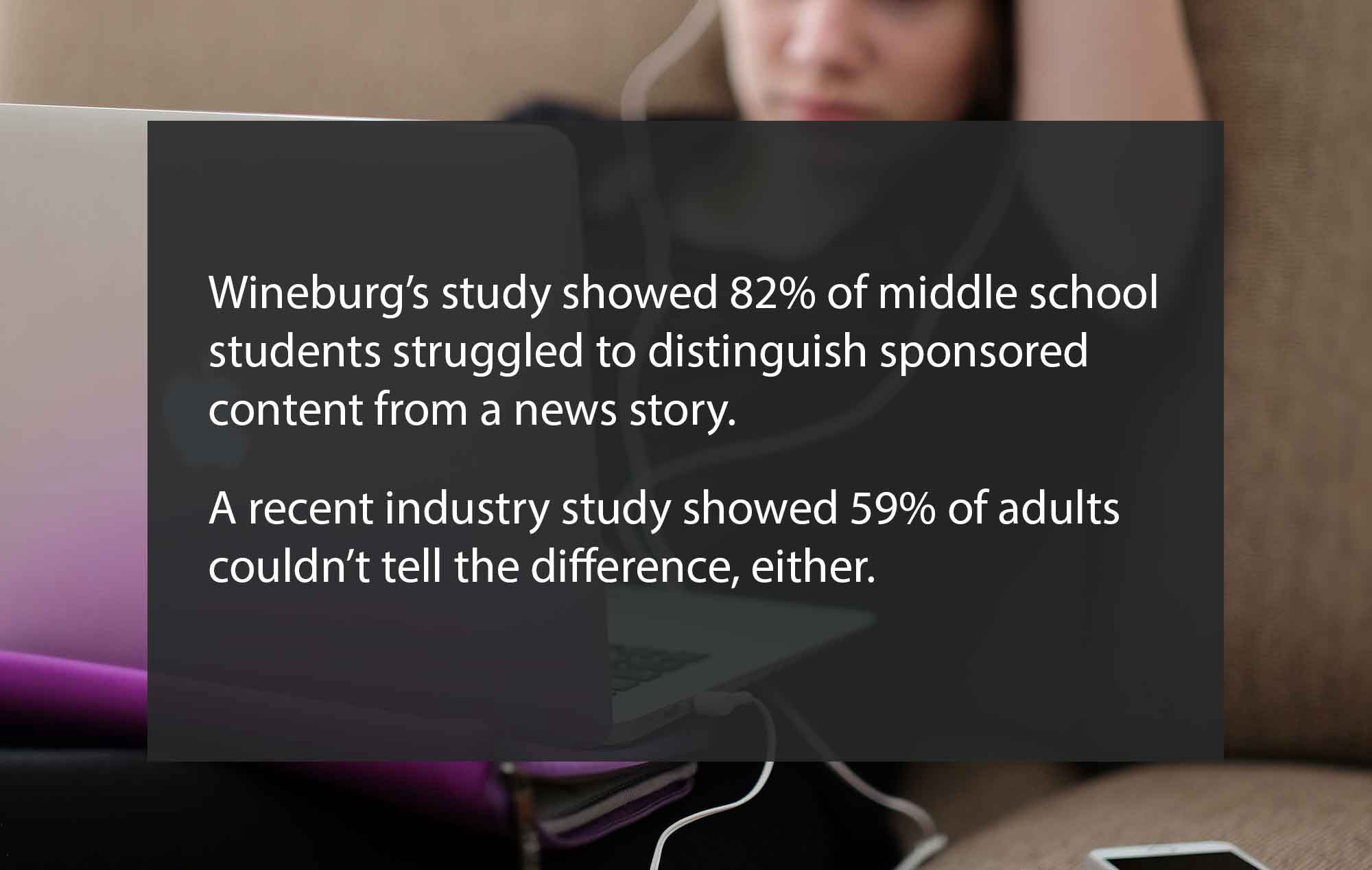

Wineburg and Sarah McGrew, a doctoral candidate in education, tested the ability of thousands of students ranging from middle school to college to evaluate the reliability of online news. What they found was discouraging: even social media-savvy students at elite universities were woefully unskilled at determining whether or not information came from reliable, unbiased sources.

Read about Sam Wineburg’s study. Read Wineburg’s take on what schools can do. Read the IAB Edelman Berland summary.

Read about Sam Wineburg’s study. Read Wineburg’s take on what schools can do. Read the IAB Edelman Berland summary.

Is this a blind spot limited to kids who have grown up taking for granted that what they read on screens is true?

Unfortunately, no. We’re all “coming of age” in what Wineburg says are the birth pangs of a Post-Gutenberg moment. “We’ve invented tools that right now have the best of us rather than us having the best of them. And we’re trying to cope with the consequences. If we are becoming informed through feeds that come across social media, then we are obliged to have at our disposal two or three basic tools to allow us to ascertain whether something that has come across our feeds is worthy of belief or whether it . . . is intended to deceive.” Wineburg and McGrew went to professional fact-checkers to see what was different about how they attack a story from a new source or unfamiliar site.

Read laterally, not vertically

In the same way hiking in unfamiliar terrain without orienting yourself on a map would be a huge waste of time and energy, so is going deep into a story or unfamiliar site before you know who is supplying the information and what their stance is.

When you encounter that intriguing story in your Facebook feed, before getting deep into it, open another browser tab and “…find out ‘what is this organization?’” Wineburg says. “When you come back to the original web page you evaluated, you have a much better sense of where that information is correct, where it is fallacious, whether it’s reliable, and whether you want [it] to build your rapport for your article or inform your own opinion about what that article contains.”

Look beyond the About page

You’ve never heard of this particular organization but their website looks thorough and their About page mentions some credible sounding backers. Wineberg says to keep looking. With a little cunning and some basic skills, anyone can create and run a site from their kitchen table that looks and sounds reliable (or unbiased, or “funded by the citizens”. . .you get the idea).

Moreover, with a little viral social media help, Wineburg says those sites (and their stories) can achieve clicks, likes and comments that rival highly circulated newspapers.

A simple way to begin vetting an unknown site is to search for the organization’s name in quotes. This will turn up mentions of the organization in other articles and on other sites, which can help you determine their credibility. Add terms like “funding” to your search to find out information that may not be apparent on the site.

Scroll down and click out of order

When you search on Google, the order of the results is determined by a number of factors, including how many other pages link to that page — but trustworthiness is not one of them. The top results are not necessarily unbiased or the most trustworthy. Fact-checkers scroll down and read the urls and abstracts to make an informed decision about where to click first.

Google puts a world of information in front of you. But that means there are front groups and fake news sites right next to legitimate and reliable sources. You have to know how to to find the difference (hint, go back to steps 1 and 2).

“Accurate information is an absolutely essential ingredient to civic health,” says Wineburg. “Reliable information is to civic health what clean air and clean water are to public health. And so, if we are making decisions as voters based on fallacious assumptions because we haven’t done due diligence and even surpassed a modicum of checking about the quality of our information, then when we press the lever in the ballot box, we are operating on a shaky foundation.”

We may not be able to stop the stampede of news coming at us, but we can better wrangle it, giving our precious time to the sources we are confident are worth our time and making the best decisions possible for our future.