THIS SATURDAY MORNING AT 8:10 A.M., I was lying in bed, about to meditate. I try to do this most days. This time, I was on vacation in Honolulu, lounging in bed in an historic home high above the ocean. I grabbed my phone to pull up the meditation app.

Here is the text I saw:

“BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

I deleted it. In the moment, I figured it just had to be spam.

Then my son and husband walked into the bedroom. They’d gotten it too. As had our Airbnb host, who was now knocking at our front door, telling us itwas real, and to draw down the shades, bring in the bottles of water on our front porch and “shelter in place.”

It is one thing to report on the existential North Korean nuclear threat, as I did recently for a set of essays by Stanford faculty experts. It is entirely different — and a horrific throwback to my Cold War childhood — to be alerted that you might be blown up by an incoming nuclear bomb.

As the sun shone outside, I drew the blinds over the massive windows. It struck me how ridiculous this was as a strategy.

We gathered in the downstairs hallway, my son and daughter, her husband and mine, sitting on the carpet with our cell phones. The radio was no help: music, and then a report on DACA.

We listened for air raid sirens. There were none.

We searched the web for “where do we shelter,” “how long does it take an intercontinental ballistic missile to reach Hawaii from North Korea” (somewhere around 20 minutes) and “Hawaii’s missile defense system” (they recently conducted successful trials).

We said, “I love you,” and that we were glad to be together.

After about 10 minutes, I found a few tweets saying it was a mistake, but these were from random people. There was virtually nothing credible online.

It was 20 long minutes before we found a CBS News post that the alert was an error. Then ABC, then CNN. A second knock on the door and it was our host again. He’d seen the posts too. We took it as an “all clear.”

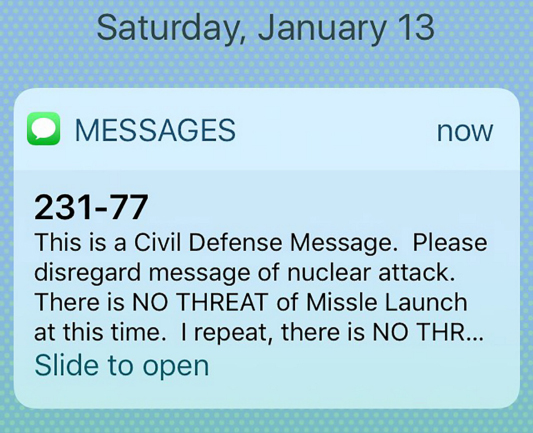

At last, 38 minutes after the initial warning, we got a second alert via cell phone. The first alert had been a mistake.

“There is no missile threat or danger to the State of Hawaii. Repeat. False alarm.”

We sat stunned, still wearing our pajamas.

Little by little, stories started trickling in.

The young couple next door had been out to breakfast in Waikiki. When the alert hit, everyone ran outside. People jumped in their cars, trying to get home, and creating chaos and traffic.

At the beachfront hotels, there were announcements to seek shelter, but the hotel staff had no idea where or how.

The Los Angeles Times reported they had video of adults “removing manhole covers and lowering children into sewers in a desperate attempt to escape a ballistic missile hurtling their way.”

The New York Times said, “Breaking News: No one is bombing Hawaii.”

It is clear no one knew exactly what to do.

What is also clear, after this morning’s terrifying mistake, is that we are not prepared. But is there really a way to prepare for Doomsday?

Melinda Sacks, ’74, is a senior writer at STANFORD.