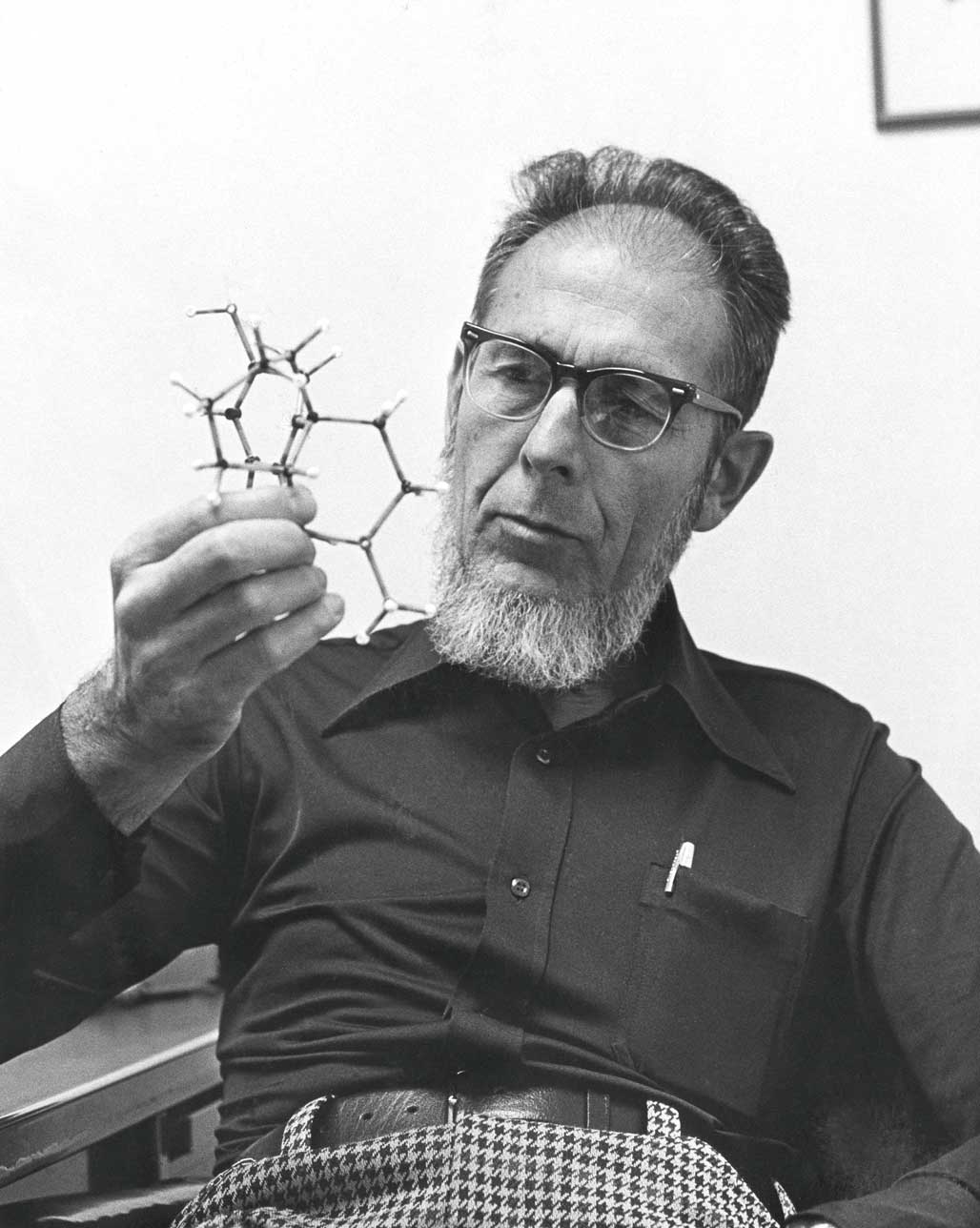

In 1979, Avram Goldstein, a professor at the School of Medicine, started to build the foundations of addiction science. He worked for decades to understand how narcotic drugs work in the brain, and he ultimately discovered one of the brain’s own endorphins.

A longtime chair of the pharmacology department, Goldstein was ahead of his time in the way he thought about drugs, the brain and society. In his 1993 book, Addiction: from Biology to Drug Policy, he wrote that drugs were a public health problem, not a law-and-order issue, and he reminded readers that even substances that were considered innocuous, like caffeine and nicotine, were also addictive. “Our society makes artificial distinctions among addictive drugs,” he wrote. “We foster the false impression that because nicotine and alcohol are legal, they must be less dangerous and less addictive than the illicit drugs.”

Taking his work beyond the laboratory, Goldstein organized the first major methadone program in California. He supervised the treatment of more than a thousand heroin addicts in San Jose, carefully doing controlled experiments to uncover the best doses of methadone for people who wanted to get off heroin. He also helped develop urine tests that identified returning Vietnam veterans who were addicted to heroin so they could receive treatment before being discharged. Goldstein died in 2012, but his influence continues through the faculty he recruited, the curriculum he shaped, and the discoveries he made about drugs and the brain.

Katharine Gammon is a science writer based in Santa Monica, Calif.