Think about a time you had to choose between jobs: say, the large corporate firm with the higher salary or the small upstart with stock options and the chance to run it one day. Or between places to live: the fixer-upper with wide, green, hammock-ready lawn or the spanking new townhouse with only a measly patio? How did you pick? Do you have any regrets?

For Sheena Iyengar, a professor at the Columbia School of Business, choice is a field of study. The Art of Choosing (Grand Central Publishing), published last spring, covers everything from her own decision-making process to clinical studies that reveal some surprising truths. For example, despite the value placed on individual freedom in Western cultures, the power to choose—or even having a wide range of options—does not necessarily make us happier.

Iyengar, PhD '98, is a petite woman, with soft dark hair and a thoughtful, musical voice that draws in listeners. "What's beautiful about choice," she says, "is that it gives meaning to everything we do. It is the only thing that enables us to go from who we are today to who we want to be tomorrow. At the same time, in order to get the most out of the choices in our lives, we must think carefully about when to pull out this tool, when to put more pressure on it, when to pull back. Each of us ought to ask ourselves, how much choice do we really need? When is it worth making a choice and when is it distracting us from our larger goals?"

These kinds of questions come from Iyengar's life, as well as her academic research. Born to Sikh immigrants and raised in New Jersey, she grew up at a crossroads of cultures. "As a Sikh, you're taught the importance of duty, to obey your elders and God. Marriages were arranged. Careers were very much guided by the elders. Usually, being a doctor or an engineer is good. Everything else is, well, not so good." She laughs. "On the other hand, I was an American, where everything is about what you want, and figuring out what you want. How you're going to do your hair, for example. And, of course, you get to decide what you're going to be when you grow up. I remember coming home and saying these things to my mom, and she was like 'what is this nonsense?' "

Those choices were made more complex when Sheena Sethi learned at age 3 that she had retinitis pigmentosa and was going blind. By 10, she could no longer read or write. By 16, she was left with only the perception of light, and soon that began to fade. "On the one hand, when you talked about the American dream, you can do whatever you want as long as you put your mind to it. On the other hand, I'm being asked: Can she go to a normal school? Can she study science? Can she shave her legs?"

These challenges taught her to fight for what she wanted. When her high school guidance counselor didn't even bother to show her a college application manual, she applied to the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania and got in, early admission. Professors worried that she could never be a trader (she couldn't see the computer screen) and companies declined to give her summer internships. She took a class in social psychology and learned how to become an experimentalist, majoring in statistics.

Iyengar moved on to Stanford and later made two now-famous experiments. The "Mom study" reflected some of her own feelings about being Sikh American. Seven- to 9-year-old Asian- and Anglo-American children were divided into three groups that either picked which learning activity they wanted to complete, completed the activity their mothers had chosen for them or completed the activity the experimenter had chosen.

Anglo-American children performed better when they chose the activity themselves, and more poorly when they were not permitted to do so. Asian-American children, however, performed best when Mom chose. "What we learned," says Iyengar excitedly, "is there are conditions out there in the great world in which having somebody else choose for you can help you do better than when you choose for yourself."

Interestingly, Iyengar herself did not choose Stanford for her doctorate; her adviser at Wharton did, even though Iyengar preferred Yale.

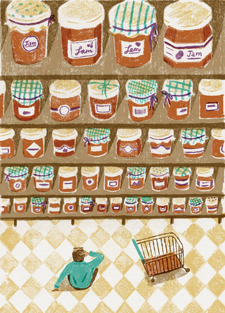

Iyengar's next experiment would put her on the map. She set up two jam-tasting kiosks in the Bay Area's upscale Draeger's Market. One kiosk offered 24 different flavors, tempting 60 percent of all shoppers to stop and sample. The other kiosk had six types of jam, attracting 40 percent of the shoppers. But only 3 percent of the people who sampled 24 varieties actually purchased jam. Of those who stopped at the six-flavor kiosk, 30 percent bought.

"Cognitively, we just have a harder time doing the math, comparing and contrasting so many different prospects," explains Iyengar. "Also, in the modern individual, we feel obliged to be free. When we make a choice, it's much more complicated. It's an act of communication. First, the choice means deciding who we are and what we want, and secondly, that choice has to send the right message to other people—about who we are and what we want." Buying hazelnut-flavored instant coffee says something different than buying organic, shade-grown, fair-trade coffee.

As a business tool, the jam study's impact has been tremendous. Malcolm Gladwell, author of Outliers and Blink, points out, "The real value of Iyengar's work has been in providing a scientific basis for marketing. Prior, there had been a kind of fetishization of choice in many different areas of the commercial world. It didn't have any theoretical basis. . . . What Iyengar has done is brought a real level of sophistication and nuance to the question of understanding consumer behavior."

In her own life, choice—or the lack thereof—became all the more relevant when she met her future husband, Garud Iyengar, PhD '98, at the top of the Oval, boarding the Marguerite headed for Escondido Village. He was an engineering candidate. Bus-seat banter turned into friendship, which blossomed into romance. But he was Hindu; the family religions didn't mesh. Until a local soothsayer was called in, claiming, "These two have been married for seven lives; expect them to be married for seven more."

"And that," Iyengar says, chuckling, "for my mother-in-law, was destiny."

Her dream project is to create a global index for choice—an undertaking that recently got a kick-start with funding from the Chazen Institute at Columbia. "Essentially, we're looking at people's perceptions of how much choice they have and how much choice do they want. Which is interesting, say, in ex-communist countries and Arabic countries. Where and when does choice—or lack of choice—improve ordinary lives?" The first round of surveys takes in Brazil, China, India, Japan, Russia and the United States. People from all walks of life are being asked about preferences in everything from soda to housing, education, health care, politics and religion. In each case Iyengar wants to know, "Would people like more choice or less? We also want to know their opinions on how best to make these choices." She hopes the survey eventually will cover 40 countries.

Asked how she feels about her own successful professional path, Iyengar shrugs modestly. "Any one of us can tell our story in terms of fate, in terms of luck and in terms of choice. I'll never know with exact certitude what is working."