"My dear uncle I am pleased to meet you here this morning," Leland Stanford Jr. wrote—after his death in 1884—to his uncle, Thomas Welton Stanford.

The message appeared at a séance led by Fred Evans, a then famous spiritualist who claimed to channel messages from departed souls straight into chalk sentences scrawled on closed (sometimes locked) slates. Working for T.W. Stanford, Evans produced messages in which Leland Jr. pledged familial affection, offered consolation and gently reminded his uncle to do his best to "please the medium" (the séance equivalent of "don't forget to tip"). T.W. eventually donated these slates to the boy's namesake: Leland Stanford Jr. University. Some two dozen small boxes in Special Collections contain varied and curious remnants of T.W.'s spiritualist pursuits.

Many in that era thought that direct contact with a world of spirit was possible. Believers were certain science would prove them right, and spiritualist teachings incorporated 19th-century inquiry into the nature of matter, force and the universe. Yet while some mediums believed in their alleged spiritual abilities, many more were outrageous hoaxers.

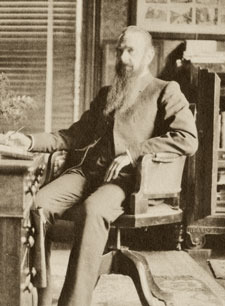

Thomas Welton Stanford, one of Gov. Leland Stanford's five brothers, moved to Australia as a young man and made his fortune selling American goods and local real estate. He never left Australia, even after becoming a Stanford University trustee. T.W.'s correspondence reveals a man who was wealthy, lonely and morose. After the death of his wife, he became increasingly interested in spiritualism. By the time he died in 1918, he had hosted many hundreds of séances attended by the crème of Melbourne society.

Most of his séances featured medium Charles Bailey, whose specialties included possession by a dead spirit (called a "control") and the spontaneous movement of physical objects (called "apports") from distant lands, through "the astral plane" and into the séance room.

Most of Bailey's séances began with a search of his person (excluding his underclothes) and a prayer. Bailey proceeded to adopt the character of a "Hindoo" control. Attendees were told to darken the room and sing a hymn, during which time Bailey-as-Hindoo would produce an apport or two. The apports were said to have distant or antique origin—coins, shards, weapons, religious objects and "hieroglyphic" tablets or scrolls. Bailey also liked to produce natural objects such as seeds, nests, eggs, and even the occasional fish, small tortoise or terrified bird.

At Bailey séances, the production of an apport was usually followed by a lecture—delivered in-character as one of several deceased academics—on the apport. T.W.'s belief in the séances was enhanced by his opinion that the mundane Bailey didn't seem to have the intellectual chops to produce esoteric lectures, whose transcripts ran to 15-plus pages.

Bailey's reign on the Melbourne social scene ended abruptly in 1914, when he learned that T.W. planned to bring a Stanford professor to Australia to conduct strict tests of the medium's abilities. Bailey skipped the continent for an "extended tour" of America and Europe—and went on to be championed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the relentlessly logical Sherlock Holmes. T.W.'s private secretary wrote that his employer was "greatly distressed" by Bailey's conduct.

The specters of skepticism came to roost next to the spirits of hopeful belief. When Thomas Welton Stanford passed away in August 1918, his final will included a careful note that his bequest to the University could be used for either psychic or (by then far more mainstream) psychological research.

Jenny Pegg is a doctoral student in the history and philosophy of science and technology.