Everyone remembers having one teacher who was always covered in chalk. I get to be that teacher now: I’ve got chalk dust in my hair, on my face, all over my jacket. Miners get black lung; I’ve got rainbow lung from the constant inhalation of colored chalk dust.

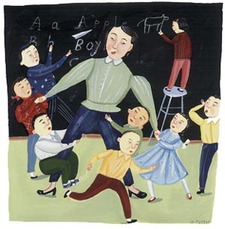

After graduation I traded the Farm’s lecture halls for the war zone that is my classroom. I try to keep 36 first-graders from flipping over their chairs, leaping onto their desks and screaming, “Miss Jessica! Miss Jessica!” at the top of their not-so-little lungs. The good news is that I’ve come to see their noise and activity as signs of engagement.

The bad news is that at any one time during my class, about a third of my kids are picking their noses and another third are crying or whining about how so-and-so took their eraser. The last third appear to be deep in thought—they might actually be listening; then again they might be thinking about picking their noses or selecting an infraction worthy of a fine whine. It definitely makes for an interesting classroom environment—and one where you learn to pick your battles.

For example, take Paul. Paul sits by himself in an island in the middle of the classroom with all the other children several feet away. Why is that, you ask? Is Paul dangerous to the other children? Hardly. Paul needs the entire center of the classroom so he can writhe on his belly, break-dance and take victory laps around his desk to celebrate the glory of each correct answer he gives. Paul was just not meant to be caged in a chair.

You call on Tom, and he scratches his nose, thinks for a while, and then answers with his arms out in the air, like a bird in full wingspan. Usually he’s wrong, but he’s just as happy when he’s wrong as he would be being right. You can’t scold Tom because the world needs more happy kids like him.

Lily is the darlingest of the darlings. So what if I’ve not cured her of the rising intonation that makes her sound like a miniature Valley Girl? Whose every utterance? Sounds like a question? It’s like a soundtrack for the classroom. “Good morning, Miss Jessica?” “I am 6 years old?” “I have to pee?”

With kids like these, there is never a dull moment in my day. Even the crying sometimes provides amusement. One day Julia burst into tears. When I asked her what was wrong, she told me that she needed to go to the bathroom. I couldn’t understand why this matter had risen to the level of a crisis: I let my kids use the bathroom whenever they want. I urged Julia to run ahead to the little girls’ room, but she told me—and the whole class—that she had run out of toilet paper.

I remembered that I’m not in Kansas anymore. In fact, I’m in a land somewhere-well-over-the-rainbow called China, where kids (and teachers) are expected to carry their own stash of TP.

As a Chinese-American, I thought that coming to China wouldn’t be too overwhelming a change. My mind’s eye pictured docile, reticent little Chinese children, eager to listen while I read from the stack of children’s books I brought with me. Instead, I found myself among 130 hyperactive first graders who cycle through my classroom each day grabbing erasers, each other’s ears and some of the syllables of English I impart.

Amid the chaos, though, I have been able to discover a different (and perhaps better) version of myself. They have taught me not to sweat the small stuff. They have taught me that, the world over, people are characters who are going to stay characters. They have told me their stories, vastly improved my Chinese and provided me with hours of entertainment.

With each day, life in China seems less and less like an extreme sport and more like plain life. Because don’t think for a minute that my kids and I weren’t quick to share some toilet paper with Julia and move on.

JESS DANG, '03, taught English at Suzhou International Foreign Language School, about an hour west of Shanghai.