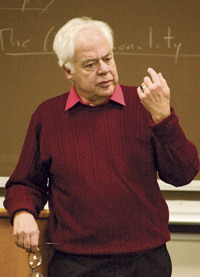

RICHARD RORTY built a career on some of the most complex intellectual ideas around. He challenged the assumptions held by his fellow philosophers—the very people exploring assumptions about life. But he also was devoted to simple things—a patch of orchids or catching sight of a rare and beautiful bird.

Rorty, a professor emeritus of comparative literature at Stanford and a winner in 1981 of one of the first MacArthur "genius" grants, died on June 8 of pancreatic cancer at his campus home. He was 75.

He was born in 1931 in New York City into a family of ardent leftists; his grandfather was a theologian who challenged the inerrancy of the Bible. Rorty began undergraduate studies at the University of Chicago when he was only 15. He earned a PhD in philosophy at Yale, served in the Army and taught at Wellesley and Princeton.

Breaking with the philosophical pack, Rorty published Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature in 1979. The book emphasized pragmatism over epistemology—arguing that philosophy should address the contingent ways people cope with real-world situations, not just analyze what can and cannot be known. He also focused on the relationship of philosophy and language. Critics on one hand accused him of relativism; on the other of irrationalism.

Undeterred, Rorty dipped his feet into political criticism, arguing that the Democratic party had neglected its roots and failed to build a base that could win an electoral majority. At the same time, he railed against the Bush administration. "He never forgot that philosophy—above and beyond objections by colleagues—mustn't ignore the problems posed by life as we live it," German philosopher Jürgen Habermas wrote in a tribute to Rorty after his death.

Rorty is survived by his wife of 34 years, Mary Varney Rorty, a faculty associate at the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics; three children, Jay, Kevin and Patricia; two grandchildren; and his former wife, philosopher Amelie Oksenberg Rorty.