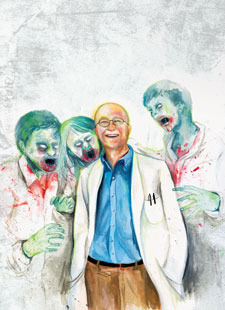

One night in 2009, horror movie lover Steven Schlozman decided to stay up late to watch George A. Romero's 1968 cult classic Night of the Living Dead. The zombies' dead eyes, shambling gait and insatiable hunger all aroused the diagnostician in Schlozman, a child psychiatrist and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. "What the hell is wrong with the brains of those ghouls?" he wondered.

To answer his own question, Schlozman, '88, dusted off his English degree and wrote a fictitious paper on a virally transmitted disease he dubbed Ataxic Neurodegenerative Satiety Deficiency Syndrome. His imaginary co-authors included one living, two dead and one "humanoid infected." The zombie part of the medical mystery is all in good fun, but the diagnosis is based in real science.

The etiology of zombiism, according to Schlozman, involves a virus that destroys much of the brain's frontal lobe—the seat of higher cognition and regulator of our baser impulses. Stripped of this moderating influence, the brain's unchecked amygdala, what Schlozman calls our "crocodile brain," drives victims into a state of unrelieved rage. Meanwhile, damage to the cerebellum impedes balance, sending zombies lurching forward in their wide-legged shamble. Damage to the ventromedial hypothalamus blocks any feeling of satiety, producing a never-ending hunger.

And the moaning? In a word: constipation. An all-brain diet is too high in protein and entirely void of fiber. Now you know.

To explain the monsters' brain lust, Schlozman waxes philosophical. "Zombies lack the essence of humanity," he explains. "They hunger, literally, for their humanity—and their humanity resides in gray matter. It's Cartesian dualism with cheesy music and bad makeup."

Schlozman, who has authored 70 bona fide scientific articles, uses the premise to make neuroscience engaging for students and, increasingly, for members of the media who crave an actual doctor's take on the well-worn subject. He is partially to blame for a widely read blog post from the usually straight-faced Centers for Disease Control, which earlier this year cited his work in using a "zombie apocalypse" scenario as a pretext for teaching disaster preparedness. Schlozman was as surprised as anyone to find the CDC referencing his fake paper.

Given that his psychiatry practice helps kids work through real nightmares, it may seem odd that the doctor spends his off hours dreaming up imaginary ones. But Schlozman says horror stories can play a role in therapy through displacement. They offer a side channel for dealing with something awful, without having to face the unbearable head-on. The strategy works especially well for kids who lack the maturity and language skills to grapple with complex problems. Most children won't be drawn into direct discussions about their troubles, Schlozman says. "Instead we'll talk about a video or a movie, when we both know what we're really talking about."

Schlozman knows from personal experience that displacement has its place. The night he watched Night of the Living Dead he couldn't sleep because his wife, Ruta Nonacs, had just been diagnosed with breast cancer. "I felt like my world was ending," he says. Watching people kill rampaging zombies served as a cathartic alternative to his own thoughts. Nonacs has since recovered and, Schlozman says, they enjoy a "Norman Rockwell life" with their two young daughters in a Boston suburb.

Since zombies lurched onto the big screen 40 years ago, the creatures have embodied the deepest fears of every age. Romero made his first zombie movie in response to the Cold War. His next one, 10 years later, was a commentary on consumerism. Today, Schlozman thinks modern life brims with numbing zombielike experiences, like waiting for hours at the DMV or trying to speak with a human when you call customer service. Zombies embody these life-sucking moments in a monster that needs killing. "They are, by definition, heavy-handed blunt metaphors," he says. "If you are killing walking corpses not only is it okay, it's kind of your duty."

Schlozman further explores these ideas in The Zombie Autopsies: Secret Notebooks from the Apocalypse (Hachette), published last spring. The book takes readers along with a neuroscientist named Stanley Blum on a last-ditch United Nations mission to a remote island. There, Blum vivisects zombies in order to discover the pathogenesis of the pandemic and find a cure before it wipes out humanity. Written as the doctor's journals, the book is filled with fairly gory medical illustrations. Unless you have a strong stomach, you might wish to refrain from reading it over lunch.

The book is selling briskly enough that the first-time novelist's agent wants a zombie sequel and Schlozman has nearly finished a second novel on a different subject. In July, he had his own booth at Comic-Con, the annual comic book and fantasy conference in San Diego that draws more than 125,000 people. "It's so weird to be in this strange place where people dressed like corpses cheer for you," he says. "I think I like it."

It's certainly a far cry from his day job counseling young patients at Massachusetts General Hospital or in his private practice. Schlozman also teaches introductory psychiatry classes and, for a splash of real-life gore, organ transplantation, to medical students. Between his professional duties and shuttling his kids to soccer games, he usually manages to write for two to six hours every week.

Rather than cause consternation among his clients, Schlozman's growing role in the zombie zeitgeist has been a boon. Usually, he says, parents have to drag kids in to see a shrink. But when they hear about his zombie work, "The kids are like, 'I'll see this guy.'"

The most exciting part of his second career is that Romero has taken him under his wing. The director sends Schlozman old horror movies to watch and is working on a script for a film adaptation of The Zombie Autopsies. In Toronto, where Romero lives, they went to see the premiere of Survival of the Dead together. In Boston, they took in a stage production of Richard III. It was a modern interpretation in which the deformed king dispatched one victim with a chain saw. "It was an homage to every horror movie ever made," Schlozman says. "At one point, I leaned over to George and said, 'You know this is your fault, don't you?'"

"Sometimes," Romero responded ruefully, "even I want the classics to stay classic."

Ann Marsh, '88, is a writer in Los Angeles.