In the early 1990s, Robert Vitalis was on a fellowship at Princeton preparing a book about the Arabian American Oil Company. One day in a seminar room, he overheard two young history professors discussing Wallace Stegner.

Was this the same Stegner who had written a book about American oil interests in Saudi Arabia? Vitalis asked. Nope, the professors assured him. The Stegner they were talking about was a Pulitzer-winning novelist and a pioneering voice in the fight to save our natural environment. He never wrote a book about Saudi Arabia.

They were wrong. Vitalis, now an associate professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, eventually learned that the Stegner who founded Stanford’s creative writing program was indeed the author of Discovery! The Search for Arabian Oil, a tormented work-for-hire project about the early days of Saudi oil exploration in the 1930s and 1940s. Discovery! was serialized in 14 issues of the Arabian American Oil Company magazine Aramco World, beginning in 1968, 12 years after Stegner had turned in his manuscript to Aramco’s public relations department. Although eventually published as a book by Beirut’s Middle East Export Press in 1971, it has never been widely available.

“No one talks about the Saudi book,” Vitalis said during a telephone interview. No one, that is, except Vitalis. He is the first to tackle Stegner’s “lost” book in depth and has written “Wallace Stegner’s Arabian Discovery: Imperial Blind Spots in a Continental Vision,” which will appear in an upcoming issue of Pacific Historical Review. By comparison, the hefty 500-page Stegner biography by Jackson Benson, ’52, mentions Stegner’s Arabian adventure briefly in a few pages; it was one of the few times Stegner wrote about a foreign country and was his only book about one.

But Discovery! struck Vitalis as exceptional for another reason. As the political scientist had learned at Princeton, Stegner was an iconic figure to environmental and social historians—a man who decried the exploitation of the American West, campaigned tirelessly for federal protection of U.S. wilderness areas, worked for local conservation causes, and in 1961 served as an assistant to Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, known for his environmental activism. What was Stegner doing writing for a company whose unbridled exploitation of foreign resources and people had captured Vitalis’s scholarly interest?

Over the next decade, in the course of Vitalis researching his book America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (Stanford U. Press, 2007), Vitalis would uncover the complexities of Stegner’s experience with Aramco.

For the United States, the post-World War II period was one of optimism, triumph and a sense of adventure. The world was America’s oyster, and American culture often betrayed a comic-book conception of internationalism. Yul Brynner was Dmitri in Hollywood’s take on Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov; Gina Lollobrigida, with her shimmy and shake, was the biblical Sheba; Rocky outsmarted Natasha and Boris every time in the Bullwinkle ’toons. Western movies showcased Americans prevailing over their enemies in a hostile environment filled with redskins wielding tomahawks. The country saw itself as a progressive force in the world, and in the postwar era few had the energy or resources to contradict such a picture.

In keeping with the zeitgeist, Aramco, then the largest private U.S. investment overseas, launched a massive public relations effort to present itself as a benevolent force in the Middle East. The campaign came in the wake of longstanding criticism.

“There’s a very long tradition in the United States of criticizing the machinations of the oil companies,” Vitalis says. “Upton Sinclair’s book Oil! in the 1920s is a thinly disguised story of the Teapot Dome Scandal” involving corruption, payoffs and domestic oil reserves. “There have been lots of populist attacks on oil companies throughout the 20th century.”

“There was always a feeling the oil companies were making too much money—and actually, they were,” says Donald McDonald, a historian for the Los Altos History Museum who has written about the role of Los Altos residents in developing Arabian oil and who helped mount a major exhibition on Stegner in 2005.

By 1947, some U.S. senators were decrying Aramco’s price-gouging and calling for an investigation. Less than six months later, they accused Aramco of an “avaricious desire for enormous profits” and of overcharging the Navy by $30 million to $38 million for Arabian oil. According to the New York Times, the reconfiguring of oil companies, their subsidiaries and the governments behind them created “one of the most baffling corporate complexes of modern times”—and one that constantly threatened to destabilize the precarious balance of world powers.

Moreover, the disconnect between American values trumpeted abroad during the Cold War and the persistence of segregationist practices was becoming untenable. Aramco’s Saudi workers lived in substandard conditions and had no chance of advancement, unlike American employees. When workers rioted and held a general strike in 1953, some 100 of their leaders were arrested.

The company’s need for spin was enormous. Aramco hired journalists in Cairo and Beirut and produced feature-length movies. It subsidized scholars and built Middle East centers at American universities. The Aramco World index, from 1949 to 1983, is an astonishing chronicle documenting the efforts of the company’s magazine to establish its cultural, historical and aesthetic interests in articles such as “The Marco Polo Route,” “The Beauty of Bedouin Jewelry,” “Ephesus: Hostess to History,” and “Christmas in Bethlehem.”

“It was the prototype of a rich company putting out a very fancy publishing house,” McDonald says, “a wholly owned subsidiary that gives you the idea that they were a benign organization, and the government criticism was unfair, because they were doing a great thing. In other words, they had a PR problem from the beginning. There was a lot of knowledge in leftist circles that all was not well.”

Stegner was not immune to the general surge of postwar optimism. When a former student from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference who had become a public relations man for Aramco approached him in 1955, Stegner agreed to the book project, Benson explains, especially because Mary Page Stegner, his wife of 20 years, had fantasies of visiting the land of Arabian Nights. Stegner made his point of view clear to the company: “I have no liking either for muckraking or for whitewashing jobs; I should very much like to make this book straightforward and honest history. . . . To do that properly I shall need my elbows free,” he wrote.

The money was good: $6,500 for 13 weeks’ work—“a princely sum for his labors on behalf of Aramco, some $42,000 in today’s terms,” Vitalis writes. The perks were equally first-class: “It was kind of nice for an old English professor to operate in terms like that,” Stegner told biographer Benson. “When I was working on it, I thought it was a marvelous story, a sort of modern Hudson Bay or East India Company adventure.”

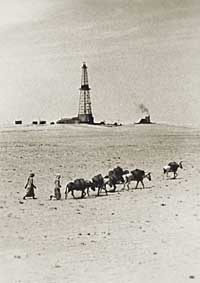

The Stegners left for the Middle East aboard Aramco’s Flying Camel in November 1955. For Stegner, it was indeed an adventure: he traveled by truck and small aircraft, interviewing old-timers from the pioneering days of the 1930s, investigating topography, and looking at the earliest wells. In Discovery! he writes:

This was Arabia as a romantic imagination might have created it; nights so mellow that they lay out under the scatter of dry bright stars, and heard the silence beyond their fire as if the whole desert hung listening. Physically, it might have been Arizona or New Mexico, with its flat crestlines, its dry clarity of air, its silence. But it felt more mysterious than that. . . .

Mary Stegner’s disillusionment came first. “When we arrived there, it was no Arabian Nights at all. It was just a kind of shack, it seemed to me,” she told Benson. “Air-conditioned shacks with a great big swimming pool in the middle with a canvas over the top. And that’s where all the wives spent the days, because we were not allowed to go out with our husbands or out into the countryside to see anything.”

Stegner sympathized with her plight: “I got to go out into the deserts quite a lot with geologists and drillers and other kinds of people, but Mary got stuck in the compound where Muzak played endlessly over the radio . . . and by the pool you sat and disconsolately drank your jungle juice.”

His own disillusionment would follow. The year 1955 was a time of intense labor trouble in the camps, forcing Stegner to reconsider whether he could write an honest account with his “elbows free.” As he wrote in a letter from Arabia, “it is . . . clear that a good deal of the story can hardly be told now, except for the company files.” That was a harbinger of trouble.

On his return home to Los Altos, Stegner wrote quickly, banging out a 357-page, triple-spaced manuscript in 13 weeks, driven by deadlines and his constant, and needless, anxiety about money. He had had an impecunious childhood, and he never got over his fear of the wolf at the door.

“I feel like a juggler with eighteen knives in the air,” he wrote to one acquaintance. And to another: “If I ever write 80,000 words in a month again, for any price, take me to Bethesda and have my head examined.” He needn’t have worried about deadlines: the project was squashed, and the manuscript was deep-sixed for a dozen years.

“You can find an explanation in the [company] documentation why they did not publish in 1958,” Vitalis says. “They read the book and thought Stegner was a racist.” The charges were unjust, he says, but reflected the growing queasiness within Aramco itself.

Benson lauds the book as featuring “heroes . . . who have guts and integrity.” But Aramco executives complained the Stegner manuscript denigrated the Saudis in the process of praising the Americans. Geologist Tom Barger had Stegner strike all references to “coolies” and “natives” from the manuscript, although the terms were used throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. Aramco executives, in the words of one, finally “recognized that [the] effendi, coolie, raghead situation was wrong and started to do something about it.” Comparing the published and unpublished versions of Discovery! Vitalis thinks the criticisms were a self-serving smokescreen. Aramco’s concerns were not humanitarian as much as they were about the company’s financial and political interests.

“Every chapter of the draft seemed to trip an alarm,” Vitalis writes in America’s Kingdom. Aramco objected to Stegner recounting a 1930s incident in which a Texas roughneck beat a Saudi worker. Even a reference to negotiations for oil concessions as a “high stakes poker game” was offensive—it implied Aramco was trying to wring the Arabs for profits. References to oil deposits on the southern frontier underscored Aramco’s interest in boundary issues, and the conflict with British claims.

“Understated as it was, they got scared,” Vitalis says.

The cover of Discovery! is melodramatic: an Indiana Jones-type American with boots and binoculars gazes out toward the reader, another crouches behind a tripod. A barefoot Saudi king clutches his cloak; to the left, a couple embraces. The first Aramco reconnaissance airplane flies over a well fire, with billowing clouds of flame.

The back cover previews the book:

A New Zealand adventurer . . .

An Arab king . . .

An American philanthropist . . .

An astute finance minister . . .

A headstrong pilot . . .

A lovesick geologist . . .

A rugged wildcatter . . .

A North Dakota greenhorn—

thrown together in . . .

The Search for Arabian Oil

The New Zealand adventurer is neither, really. The man with the binoculars is Los Altos geologist Max Steineke, ’21, who had spent 13 years working for Standard Oil of California in Alaska, Colombia and most recently in New Zealand when he asked to be sent to Arabia. Steineke “was the first man on the scene to understand the stratisgraphy and the structure under eastern Arabia’s nearly featureless surface,” Benson writes. He was “no son of a bitch for civilization,” according to Stegner.

Steineke certainly looks like an adventurer. In one photo, he grins from beneath the traditional checkered Arab headdress, like a kid at a frat costume party. His hands are freckled and his loafers scuffed. In another, he sits on a stone in a rock-strewn desert, squinting in the relentless sunlight and banging on a rock with a hammer; the photo is captioned “dressing a rock sample.” It looks posed, a visual cliché.

In Discovery! Stegner writes:

As a field geologist he rated with the best anywhere and as a man, a companion, a colleague, he could not have been better adapted to the pioneering conditions he now encountered. Burly, big-jawed, hearty, enthusiastic, profane, indefatigable, careless of irrelevant details and implacable in tracking down a line of scientific inquiry, he made men like him, and won their confidence. He was a very pure example of a very American type and heir to every quality that America had learned while settling and conquering a continent.

In short, Indy Jones. But Vitalis points out that the photos aren’t as touristy as they might appear; the traditional attire was required to appear before King Saud, who is offensively portrayed without shoes on the Discovery! cover. Steinecke obviously donned the bisht, or cloak, quickly for the occasion, because trouser cuffs, rather than the hemline of a traditional thobe, or undergarment, peep out from beneath the loose-fitting, camel-hair robe.

According to Vitalis, there’s a grimmer story behind the playacting, and the geologists’ junket to Arabia was not just a lark. “There was no work in the United States for a professional because of the Depression, and that means they were willing to go to these godforsaken places.” Steineke’s colleague Barger, half of the embracing couple on the book’s cover, was digging coal prior to the Arabian gig, and so long as he was digging coal, he couldn’t afford to marry his beloved, Kathleen. (Their love letters were published in 2000 as Out in the Blue; Barger eventually became Aramco’s president.)

Biographer Benson writes, “one is aware throughout the book of [Stegner’s] admiration for the cooperative effort that these engineers, mechanics, and construction workers had to make in order to overcome obstacles of climate, terrain, lack of proper materials and equipment, untrained workers, and the restrictions of Saudi Arabian laws, religious customs, and tribal traditions.” But Stegner’s admiration was part of the manuscript’s problem.

The Aramco World editor defended the Stegner account he serialized: “The U.S. oilmen were mythic figures; they did overcome ignorance; they did approach Saudi Arabia with a quite different attitude from that shown by the British,” he wrote to a colleague. “It may have been greed instead of ideology but to those involved simple greed was, and is, I think, a more natural, less harmful approach—and surely the Saudis benefited in myriad ways.”

Stegner had misgivings of his own, during and after the project. Benson notes “certain implicit conflicts in the author: he admires progress, while he is suspicious of it; likes the can-do, cobble-it-together enthusiasm of the oil field pioneers, but displays an underlying unease at a project so motivated by exploitation of the land for money, even though the land is largely barren.” Benson compares Stegner’s unease with Aramco to his conflicted feelings over the Hoover Dam: his admiration for the engineering feat flipped into antagonism.

Vitalis disagrees with Benson’s reading: “For me his blind spots are: why is it okay to do foreign exploitation, even while you’re arguing for conservation at home?” He argues that the trouble lies in what Stegner scholars call his “continental vision.”

“The ‘continental vision’ saw conservation as a zero-sum game. Preserving the American West, for example, meant the increased exploitation of other places,” Vitalis explains. “Often, what was praised as cutting-edge conservation at home was denounced as emotional propaganda and short-sighted nationalism when espoused by Middle Easterners.” As Vitalis writes in his article, “The book complicates the picture that we have of Stegner as a destroyer of American western myths and a forerunner of the social and environmental turn in western history. In writing about Saudi Arabia, Stegner does all the things, deploys all the tropes that his admirers say he avoids in his work on the American West.”

Further, Vitalis charges, “he is a booster for Aramco, a mammoth oil exploration and production company. He takes the opportunity in the book’s introduction to rehearse every myth about American multinational enterprise abroad that the company had invented about itself. It ‘was magical,’ he says.”

Vitalis adds that Stegner “isn’t really doing much more in this case than echoing popular beliefs about American benevolence and then cutting and pasting from the company’s huge stock of public relations materials.”

Discovery! complicates our picture of Stegner, perhaps, but does not destroy it. As if Stegner were overwhelmed by the contradictions he faced, he finally sidesteps them gracefully by framing the events he writes about in a “once-upon-a-time” conclusion that refers euphemistically to the “modern” world of the 1950s:

The pioneer time of exploration and excitement and newness and adventure was already giving way to the time of full production, mighty growth, great profits, great world importance, enormous responsibilities, and the growth of corporate as distinguished from personal relations. . . . the American involvement in Middle Eastern economic, cultural, and political life . . . would grow deeper, more complicated, and more sobering. Not inconceivably, the thing they all thought of as ‘progress’ and ‘development’ would blow them all up, and their world with it. But that is another story. This one is purely and simply the story of a frontier. . . .

Stegner wrote that “hard writing makes easy reading,” but that formula fails in Discovery! The book makes a tough read—more a series of uncompelling anecdotes strung together, often with a grating, false-hearty tone and peppered with cowboys-and-Injuns kinds of detail. And there are thumpers like this one: “However unsteady the profile of Jiddah had been from the sea, the quay was as solid as a knock on the head.” Discovery! often feels like moonlighting hackwork, written under the gun.

“It’s not his best writing,” Vitalis asserts. “He was working nonstop to meet this contract. He cuts corners.”

Discovery! appeared in paperback edition in 1971, the same year Stegner retired from Stanford and published Angle of Repose. There’s no doubt about which book is better: the following year, he won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The nationalization of Aramco was under way.

Stegner once said, “In fiction I think we should have no agenda but to tell the truth.” And in nonfiction? As Discovery! is lifted from obscurity, scholars will be discussing Stegner’s understanding of the truth, and how much he may have compromised it, for some time to come.

CYNTHIA HAVEN is a frequent Stanford contributor, whose latest book is Three Poets in Conversation.