When the heirs of Dashiell Hammett finally felt ready to trust another writer with his legacy, the most likely suspect was Joe Gores, a fellow gumshoe-turned-crime writer. Gores, who once watched a guy destroy his own car with a sledgehammer as Gores tried to repossess it, had spent as much time pounding the San Francisco pavement in search of bad guys and good stories as his literary predecessor. In fact, Gores, MA ’61, had been one step ahead of Hammett’s heirs. A decade ago, he’d asked if he might write another installment of The Maltese Falcon. At first, permission wasn’t granted; after all, it’s tricky work finding an author who could produce a new volume about iconic private eye Sam Spade without being run out of town in a San Francisco minute.

But Gores has always been tenacious in pursuit of a thrilling tale, starting with his introduction to the mystery genre in the library of his boyhood home. “When I was 6, my Ma said I could read anything I could reach, so she made sure on the bottom shelves was Lives of the Saints, The Pilgrim’s Progress,” says Gores, describing his childhood in Rochester, Minn. But he quickly figured out how to climb to the top shelf, where Ma Gores kept the hard stuff: Agatha Christie, Sherlock Holmes and, of course, Hammett. “I still remember opening The Dain Curse. At 6 years old, you don’t know that much, but ‘It was a diamond all right...’ was the first line of that novel, and I thought, ‘Oh, God, wow!’”

Joe Gores, now 77 and living with his wife, Dori, in San Anselmo, has since written many great lines of his own, especially for the six-book “DKA Files” series about repo man Dan Kearney. He is one of only two writers to have won Edgars (named in honor of Poe) from the Mystery Writers of America in three separate categories. The other writer with that distinction is Gores’s great friend Donald Westlake, a mystery Grand Master who died last New Year’s Eve. (He and Gores once published novels in which a chapter described the same incident without letting their publishers in on the fun in advance.)

Gores first began to toy with the idea of building on his literary hero’s work back in 1975, when he published a well-received fictionalized version of the adventures of Samuel Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961), the real-life creator of pop-culture idols Spade, Nick and Nora Charles, and the Continental Op. The novel was simply called Hammett; Wim Wenders directed the movie version in 1982. But decades later, Gores still felt he had “unfinished business” with the author, so in 1999 he wrote to Hammett’s daughter, Jo Marshall, asking if the family would consider a new book based on The Maltese Falcon.

At first, Marshall said no, but later she had a change of heart. As her daughter Julie Rivett, the family spokesperson, puts it, the family felt that Gores was the right guy to take up her grandfather’s story. “He’s walked the walk as well as talked the talk. He knows as well as anyone where those characters came from,” she says.

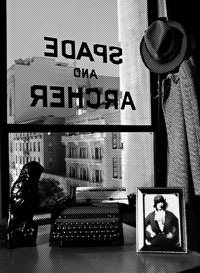

In February, Gores released Spade & Archer (Knopf), a prequel novel that explains how Spade came to seek the falcon statue that is perhaps the greatest MacGuffin in detective fiction. It is both a love letter to the original work and a satisfying read for Falcon fans that circles back to where Gores’s own hard-boiled history—and the genre’s—began: with an appreciation for the finely written line, and a nose for trouble.

Although bitten early and hard by the mystery bug, young Joe Gores dutifully put mysteries aside when he went to college—first to Notre Dame, where he studied English literature, then to Stanford for a master’s degree. “You become very highbrow when you are in college,” he deadpans. “I was writing the kind of stuff you write in graduate school, which is, you know, ‘the girl with the ponytail commits suicide.’”

One day in downtown Palo Alto, Gores happened across a paperback of Ross Macdonald stories, and just as the first line of The Dain Curse had bewitched him as a young child, again a single sentence knocked him for a loop. “The opening line of ‘Gone Girl’ was ‘I was tooling home from the Mexican border in a light blue convertible and a dark blue mood,’” Gores recalls. “And I thought ‘My God, that is the way I want to write! . . . That kind of tightness, that kind of directness, no nonsense, no navelgazing. You are in there to create vivid characters who are doing extremely interesting things and that’s it.”

This lean, action-packed style became the Gores M.O., encouraged by Stanford creative writing teacher Will Ready, who gave Gores what he calls “the best advice I ever got as a writer: Boil it down.”

First, Gores needed something to boil down, some adventures to get the blood flowing. Still mid-degree, he tagged along with a friend who was hopping a freighter to Tahiti. “That’s where I started really writing,” recalls Gores of his time in the South Seas. In 1957, “I made my first story sale there. It was to Man Hunt magazine, the last of the pulps, for $65, and it was about a guy who gets on a chain gang in Georgia.” There were rejection letters, too—Gores would paper his bathroom with some 300 of them.

The Army drafted Gores while he was in Tahiti. Initially assigned to Ft. Lewis, Wash., for two years of retyping file cards, Gores finagled a transfer after a month to the Pentagon and a job writing the biographies of generals.

When Gores returned to Stanford, he was determined to study the kind of adventurous fiction he loved, even if it wasn’t considered suitably scholarly at the time. As his thesis topic, he says, “I picked ‘stereotypes in South Seas fiction’ because almost all the people who wrote about the South Seas were pulp writers.” His adviser had never read the works Gores cited in his thesis and didn’t seek out copies.

In the meantime, Gores had been doing ride-alongs with a repo man, a regular at the gym he lived above. “He used to come in hung over as hell telling these wonderful tales of his adventures thugging cars and I thought, ‘Oh, God, that sounds really great,’” Gores recalls. He asked the man’s boss, Dave Kikkert, for a repossession job, only to be rebuffed with “College kids don’t work out.” Undeterred, Gores offered to work two weeks for free; intrigued, Kikkert gave him a file on a guy who’d skipped out on his car payments. “I talked to 167 people at 57 different addresses, trying to run this guy down,” Gores says. Then one day, Gores walked into the office, threw the file on his boss’s desk, and said, “Dave, I found the bastard. He’s down in Colma, in a grave—he’s been dead for two years!” Gores chuckles at the memory. “He gave me a file on a dead man to see if I could find him! When I threw the thing on his desk, he said, ‘You’re hired.’”

Gores’s years as a private eye with San Francisco’s David Kikkert & Associates provided the juice for his many stories and novels about a thinly-veiled repo agency called Daniel Kearney Associates. Nearly everything about the real DKA—the people, the street slang, the far-out adventures—found its way into Gores’s fiction, including the Gypsies who inspired 32 Cadillacs by making off with those vehicles in one day. (The Kikkert agency recovered 29 of them.) He was a private eye for a dozen years, with a three-year leave to teach in Kenya—“I’d been hung up on Tarzan as a kid and I always wanted to see Africa.” A seventh DKA novel is in the works.

Gores’s fiction often has been loosely based in reality. The vengeance-seeking protagonist of his first novel, 1969’s A Time of Predators, lives in a house modelled on Will Ready’s home near the Stanford golf course. And, of course, he made Hammett into a character, thanks to a serendipitous conversation he had one night while driving into San Francisco with his longtime agent Henry Morrison. “The foghorn was going on the Golden Gate Bridge,” Gores recalls, “and I said to Henry, ‘Boy, it’s a Hammett kind of night.’ Henry just said musingly, ‘I wonder what would happen if somebody wrote a novel about Hammett?’ That’s all he said, and neither one of us referred to it again. And then I couldn’t get it out of my head!”

Hammett is sort of the Shakespeare in Love of the mystery genre—Gores imagines how events in Hammett’s life could have inspired his work. “It’s a ‘what if’ book” Gores explains, borne of his empathy for another San Francisco writer who started out as a sleuth: Hammett had been a field op for the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Set in 1928 when Hammett was about to publish The Dain Curse and The Maltese Falcon, Hammett explores the tensions underlying this transition, imagining what might have happened if Hammett continued to work cases. “What if he had been forced back into the detective work he loved?” Gores wondered. “I know he loved it. But he loved writing more. Same way with me. That’s why I thought I could write this—I had been a detective, and I was now writing about being a detective, and I loved both of them very much.”

Although the plot is fiction, it’s rich in accurate geographic and historic detail. Gores’s deep familiarity with San Francisco is gleaned partly from endless consultation with helpful librarians, and partly from his days pounding the streets as a skip tracer. “When I was a repo man,” Gores says, “often I would drive 5,000 miles a month and never leave the city.” The reconstruction after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake had contributed, too: structures from Hammett’s era had been built to last. In the ’70s, when Gores was researching his book, he could walk the streets and see the city as his hero had.

While Hammett profoundly influenced Gores, those who know the work of both writers say they approach similar subjects from different angles. Hammett’s world is cynical and unsentimental; Gores’s is warmer, more playful. “Joe is much more a romantic than Hammett was,” says the dean of mystery publishers, Otto Penzler, who has published several Gores novels. “I mean it in the sense of having a positive outlook on life, to think the best of most people, to have hope and a sense of justice. Those are kind of old-fashioned romantic ideals, and I think that they make up a great part of Joe’s life philosophy.”

Indeed, Gores is known for his humility and joie de vivre, for being quick to praise the work of others, for characterizing his big breaks—selling his first DKA story to Ellery Queen, writing his first novel—as lucky moves that he wouldn’t have made without encouragement from others. He writes about the op, the cop and the con because, in a way, he admires the intelligence of each. The greatest sense one gets from Gores is that he has been having the time of his life for pretty much all of his life. The words “love” and “fun” come up in conversation disproportionately often for a man whose career revolves around larceny and mayhem, as in “I had so much fun in Hollywood,” which is how he characterizes his time as a writer and story editor in the 1970s and ’80s for shows like Kojak, Magnum, P.I., and B.L. Stryker.

And over time, he built up a reputation for the kind of precise, taut writing he’d so admired in Hammett’s work. In a Gores book, says Penzler, “Every sentence is clean. There are no wasted words. But it doesn’t mean that there’s not an elegance of prose style. There is, but he has that rare simplicity of prose that writers work so hard to achieve.”

Once Hammett’s heirs changed tack about a new Maltese Falcon book, Hammett biographer Rick Laymon put together a meeting between Gores and the family. At first they discussed a sequel to the original tale of treachery and treasure, in which Spade’s search throughout San Francisco for a bejeweled falcon leads only to a fake leaden one. “We talked about, where is the real falcon?” Rivett recalls.

But Gores quickly realized that too many of the story’s characters wind up dead or jailed for a sequel. Instead, he proposed a prequel that would introduce their backgrounds—sharp-as-tacks secretary Effie Perine, put-upon lawyer Sid Wise, sultry Iva Archer and her husband Miles, Spade’s detested partner—and set the stage for their great adventure. It’s a tricky proposition, because as any fan knows, Hammett’s characters aren’t in the business of explaining themselves. At the story’s center is the implacable and inscrutable Spade. “Who was he?” Gores muses. “Spade says several times in Falcon, ‘This is my town. You maybe could have operated here if you hadn’t run across me but now you have to deal with me.’ And I thought, ‘Why is this his town?’”

In Spade & Archer, Gores spins not one but three interwoven mysteries. “You still don’t see inside Sam Spade’s mind—you’ll never do that—but you get a little more explanation on the relationships between the people,” promises Rivett. Thanks to Gores’s painstaking historical research and his inside-out knowledge of the Hammett oeuvre, the prequel and the original interlock so neatly that even readers who have dog-eared their copies of The Maltese Falcon may read it again with a new eye. And not to give too much away, but yes, the dames still smolder mysteriously, San Francisco is still a moody crimetown, and the treasure, as always, seems to lie maddeningly out of reach.

Hammett biographer Laymon says Gores has pulled off a daunting literary task. “It’s not as if Joe disguised himself as someone else. He simply was able to somehow merge his voice and his vision with that of Hammett.” Adds Rivett: “My mom said that at times when she was reading Spade & Archer she would forget that it wasn’t her dad who had written it.”

What was it like to take the pen from one of detective fiction’s greatest idols and spin out his best-known tale? Joe Gores just boils it down: “It was fun,” he says.

KARA PLATONI is a journalist in Oakland.