Milt Ritchie stood beside the grave, feeling disappointed.

Only 15 people had come for the service. This, after so much research, so many invitations, even a little media attention. He was glad for the closure. But the poor turnout, he felt, seemed to reflect something troubling—a lack of cohesion, maybe?—ailing his local Black community.

Granted, the deceased had been dead for more than 100 years. Ernest Houston Johnson succumbed to tuberculosis at age 27 and was buried by his parents in a corner of Sacramento’s Old City Cemetery in 1898. The original wooden marker above Johnson’s plot had rotted away. Now, on a sunny April Saturday, Ritchie, MS ’75, and a handful of others had returned to the gravesite to unveil a shiny granite headstone honoring a man lost to history for most of a century—Stanford’s first African American student.

Ernest Johnson entered Ritchie’s life in August 1995, in the form of a letter from the Stanford Black Community Services Center. As part of an effort to establish a minority alumni task force, the letter said, each ethnic center was honoring the first of its community to graduate from the University.

Morris Graves, now associate dean of students, was running BCSC at the time. He had assigned a student researcher to resolve an issue that had been debated for a long time: when did Stanford accept its first Black student? Some thought it was as early as the 1920s; others claimed it didn’t happen until the 1950s. No one brought up 1891.

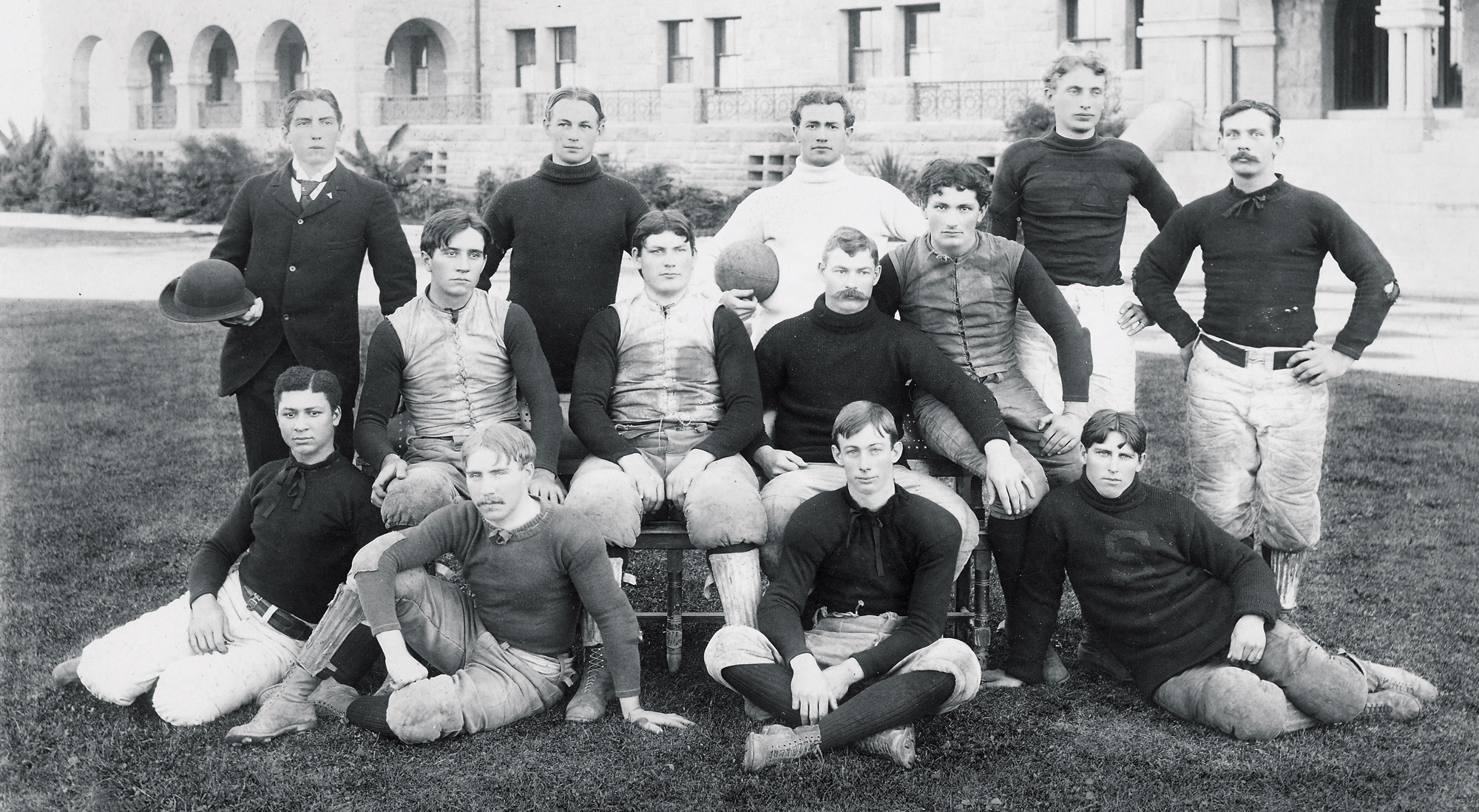

When the student discovered Johnson in an old photograph of Stanford’s first football team, the main question was answered, but dozens more rushed in to fill its place. Where had this Black student come from? What was his background? Hoping to locate a relative of Johnson’s who had supposedly attended Stanford at the same time as Ritchie, the student wrote to Ritchie asking for his help.

Ritchie, a retired chemist living in Sacramento, had felt distant from the Black community for a long while. Perhaps this was a chance to reconnect. He picked up the phone and made some calls. This is what he learned:

Ernest Johnson was born in 1871 just outside of Roseville, Calif. He was, by many accounts, an affable child, the youngest of four. Johnson’s father, Beverly, was an intellectual, though he had only a third-grade education. He owned a catering business, and in his free time studied Shakespeare—an interest he

acquired while working as a valet for Union soldiers during the Civil War.

When it came time for Ernest to begin his studies, his father bypassed the Black primary school and enrolled him in a white grammar school. The school previously had turned away Ernest’s older sister.

“This was a father who believed in his people, and he knew somebody had to be courageous and take a stand,” says Marilyn Demas, a tour director for the cemetery where Johnson is buried, and one of the first people Ritchie contacted.

Demas told Ritchie that after graduating from high school in 1891, Ernest Johnson applied to UC-Berkeley and Stanford. Berkeley accepted him. He didn’t hear back from Stanford.

Beverly Johnson knew the Stanfords through his catering business and his earlier work for the Central Pacific Railroad. Accounts vary as to how Jane Stanford discovered that Ernest had been ignored. In any case, Jane Stanford, the product of an abolitionist family, contacted University President David Starr Jordan about the matter. Soon after, Ernest Johnson received his acceptance.

Johnson was popular with his Stanford classmates. He played on the football team and supported himself working as a printer’s apprentice. He graduated with the pioneer class of 1895, with a bachelor’s in economics, and attended Stanford Law School but never received a degree.

When Johnson contracted tuberculosis a few years later, doctors prescribed “sunshine and fresh air,” and suggested he bicycle his way back to health. It didn’t work.

Johnson died on February 17, 1898. He was buried with his Stanford diploma.

Ritchie included much of this information in his reply to BCSC back in 1995. And then, for a while, he forgot about it.

At 76, Ritchie is tall and slender with a squarish white moustache, and two master’s degrees. In Johnson’s story, he recognized echoes of his own, often lonely, journey.

Ritchie grew up in west Oakland, in “the wrong part of town.” His mother worked as a housekeeper. His father worked at the post office, and nurtured a small pest-control company in his free time. Ritchie first visited Stanford as an 8-year-old on a trip sponsored by the local Black YMCA, never imagining he would one day study at the Farm.

Like Ernest Johnson, Ritchie was a rare Black face in a mostly white elementary school his father had arranged for him to attend. In middle school and high school, he was one of two Black students. Ritchie doesn’t dwell much on the racism in his own childhood, but one moment remains vivid in his mind. While visiting a swimming pool with his white friends, Ritchie was removed by the lifeguard, who pointed to the nearby pool meant for Blacks. It was covered with algae.

SET IN STONE: Ritchie led an effort to replace Johnson's rotted grave marker. The inscription on the new headstone reads ‘A graduate of the pioneer class at Stanford University.’ (Photo: José Luis Villegas)

SET IN STONE: Ritchie led an effort to replace Johnson's rotted grave marker. The inscription on the new headstone reads ‘A graduate of the pioneer class at Stanford University.’ (Photo: José Luis Villegas)

Ritchie graduated from high school in 1946, served two years in the Army, and then attended UC-Berkeley. Later, he earned a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Southern California and a master’s in materials science and engineering from Stanford, where he had won a fellowship.

He worked for a Union Oil Co. refinery, a naval weapons center at China Lake, Calif., and for Hughes Aircraft in Santa Barbara. In almost every case, he says, he was the only Black person around. “In my career, I’ve led a path that’s taken me away from the Black community. Certainly not intentionally.”

Then came the letter from BCSC, Ritchie’s research, and a newfound relationship with Stanford’s Black history. As a result of Ritchie’s research, Johnson was inducted into Stanford’s Multicultural Hall of Fame. Students had T-shirts made up: “Stanford, Black Since 1891.”

Learning Johnson’s story, says 20-year-old Abayomi Fashoro, felt “empowering.” Fashoro, now a junior, was volunteering with the BCSC in April 2003 when she asked Ritchie if he would prepare some information about Johnson for a minority alumni conference. Ritchie agreed. And then he got to thinking about Johnson’s unmarked grave.

He mentioned it to Jan Barker-Alexander, the current director of the BCSC. She said the organization would pay for a new marker. “We felt compelled, out of sheer respect” to provide a headstone, she says.

On April 17, a group gathered to place the stone and remember Johnson. Among the attendees were descendents of Johnson’s sister, representatives from BCSC, the pastor at the church Johnson’s family attended, some cemetery historians. There were prayers and speeches. Ritchie said a few words and helped unveil the granite slab.

The following Tuesday, Ritchie was at an elementary school in Oak Park, “the wrong part of town” by Sacramento standards. Most of the students are Black. Maybe there was something he could do to help, he figured, so he volunteered in a kindergarten class. “It’s time to get closer to my people.”

One day perhaps he’ll tell the children the story of the man buried with his Stanford degree not far from their school. First, he is helping them learn to read.

Jocelyn Wiener, ’99, is a reporter for the Sacramento Bee.