Looking back, the clues to David Steinberg’s crossword wizardry seem a tad more obvious than, well, the clues in some of Steinberg’s testier puzzles. (Unless, of course, you are the type who reads “Place to get drunk before getting high?” and immediately pens in “airport bar.”)

By age 1, Steinberg had not only memorized the alphabet, but also had a pet letter—a wooden “J” he toted wherever he toddled, his mother, Karen Steinberg, says. By kindergarten or so, he was taking on 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzles.

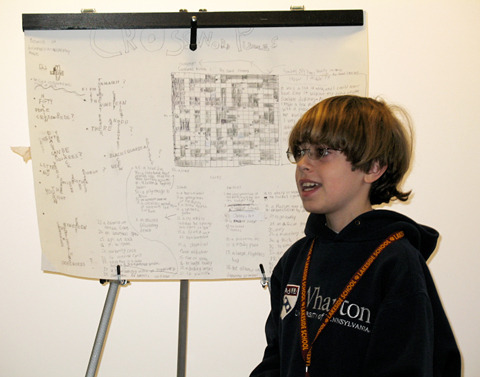

And by 10, he was starting to bring his love for both into a common focus. He made his first crossword for a fifth-grade project—a jumble of trivia and abbreviations perhaps most notable now for its cherubic swagger. “I might submit it to Will Shortz, editor and maker of the NY Times crossword puzzle,” he wrote on his presentation poster. “It really inspired me.”

It would take two more years for him to get that serious. After watching the documentary Word Play, in which a master constructor demonstrates making a crossword, Steinberg walked up to his room, pulled out some graph paper and began his craft in earnest.

After a pile of rejections and a crucial switch from paper to laptop, he scored with his 17th submission, a fiendish Thursday puzzle that required solvers to crack a code. It appeared in the Times on June 16, 2011, just days after his graduation from eighth grade. Steinberg was all of 14.

Since then, Steinberg, now a Stanford sophomore, has ranked among the most prolific Times contributors, his work appearing more than 50 times, typically on Fridays and Saturdays, the most difficult days of the week. (Puzzles get more difficult as the week advances to Saturday. Sundays are smorgasbords.)

And while Steinberg’s late-week efforts get the most attention, fellow constructors appreciate his ability to tackle the range of puzzles, including lowly Mondays, which present the daunting challenge of needing to be friendly enough for beginners and fresh enough for jaded veterans.

“There are very few people who have hit for the cycle, or publish on every day of the week,” says Jeff Chen, ’92, himself a prolific constructor who runs the blog XWord Info. “He has already done that three times over.”

Constructing for the Times and elsewhere is just part of Steinberg’s portfolio. Since he was 15, he’s been the Orange County Register’s crossword editor, an offer he got after mentioning to a reporter his interest in one day becoming an editor. “I’m still amazed they did that,” he says. “That’s so much trust to put in a 15-year-old.”

Photo: Courtesy Davd Steinberg

Photo: Courtesy Davd SteinbergIn high school, he also led an almost insanely laborious process to track down and digitize the 16,000-odd Times puzzles that appeared from the crossword’s inception in 1942 to 1993, when existing digital records began.

After realizing he’d be an old man still working on the project, Steinberg put out an appeal to the crossword community, attracting scores of volunteers from as far away as India who helped unearth all but a few of the puzzles. The digital archive is now stored at XWord Info.

Among the revelations from the effort, older puzzles weren’t nearly as musty as often supposed, although some would be unlikely to pass muster today for other reasons: One had swastika icons, another used “Recent gifts to Japan” as a clue for “bombs.” Steinberg’s database also enabled his analysis of declining numbers of female-constructed puzzles in recent decades, which spurred serious discussion about gender disparity in the crossword-constructing world.

Steinberg would love to be the next Will Shortz, whose couch he slept on this summer during an internship with the Times. (The crossword world isn’t glamorous.) With that seat occupied, Steinberg is considering his options, though crosswords will always figure highly.

“There’s something really elegant to me about interlocking words or just words in general,” he says. “It’s an art form.”

NOTE: When this puzzle is finished, connect the circled letters (not necessarily left to right!) to form an appropriate message that also forms and appropriate shape.

NOTE: When this puzzle is finished, connect the circled letters (not necessarily left to right!) to form an appropriate message that also forms and appropriate shape.