Even before the pandemic swept across campus in the fall of 1918, Stanford was a place transformed. America’s entry into World War I a year earlier had set off a rush of student enlistment. Virtually all male undergrads who remained did so as uniformed privates in the Student Army Training Corps, the U.S. War Department’s effort to harness colleges to the nation’s fight.

For Stanford’s new soldier-scholars, long days were now bookended by the blare of the trumpet: reveille at 6 a.m. and taps at 10 p.m., with precious little freedom in between.

“Fraternity life is smashed completely,” lamented Charles Sullivan, a member of Delta Tau Delta, who was struggling in his first week as a grunt. With Army boots yet to be issued, his feet were no match for double-time marches in dress shoes, he wrote his fiancée.

Blisters were soon the least of his worries. Hours after Sullivan penned his letter, his temperature spiked near 104, he fell out of ranks, and he was stretchered from his barracks in Encina Hall. The next day—October 9, 1918—the Daily gave its first accounting of a wave of illness crashing across campus. More than 100 students, it said, were under doctors’ care.

Spanish influenza—the deadliest pandemic of the 20th century—had come to Stanford. The disease had risen to military doctors’ attention that spring at an Army base in Kansas, but its true horror was about to unleash in a second, more virulent wave. October would be its deadly peak, and Stanford would not be spared.

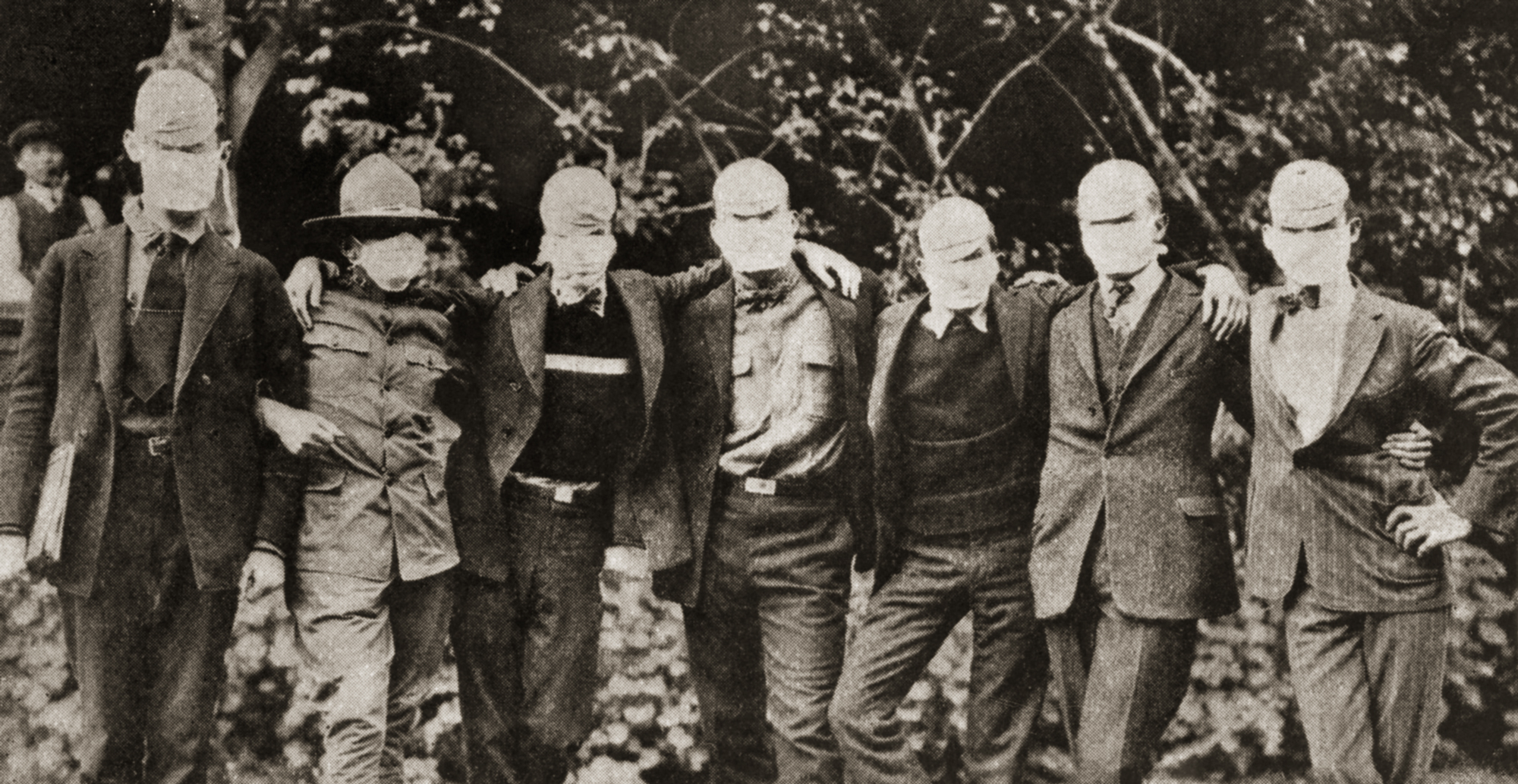

BOOT CAMPUS: Nearly all male undergraduates were part of the Student Army Training Corps in 1918. (Photo: Stanford Historical Photos/University Archives and Special Collections)

BOOT CAMPUS: Nearly all male undergraduates were part of the Student Army Training Corps in 1918. (Photo: Stanford Historical Photos/University Archives and Special Collections)

Few chapters in the university’s past are as alien to us now as the fall of 1918. The school’s about-face into a glorified boot camp was so complete that schoolwork was openly sublimated to war preparation, and male students risked reprimand for something as slight as not making their bed with their pillowcase opening to the correct side. Women had curfews tightened in response to the presence of troops near campus.

And yet, viewed now from our own time of plague, the era appears newly familiar, a kindred moment of social distancing, deep anxiety mixed with devil-may-care attitudes, and, of course, the awkwardness of life in face masks.

“Just tonight the campus has suddenly blossomed forth in white gauze masks,” Hope Snedden, Class of 1922, wrote in a letter to her father on October 24, as a university mandate kicked in. “And you can’t imagine the ludicrous appearance of a tall S.A.T.C. man sneaking into the library with one of them on, with the look of a highwayman. And you can’t recognize your friends by their eyes.”

THE COVER-UP: As in the spring of 2020, masks were required on campus in the fall of 1918, which helped protect students at assemblies. (Photo: Quad, 1920)

THE COVER-UP: As in the spring of 2020, masks were required on campus in the fall of 1918, which helped protect students at assemblies. (Photo: Quad, 1920)

The pandemic wasn’t Stanford’s first fight against contagion. In 1903, a typhoid outbreak that was traced to a local dairy killed nine students. Professor Ray Lyman Wilbur, Class of 1896, MA ’97, MD ’99, the campus physician, began rising at 4:30 a.m. to ensure that no milk left the offending farm; a shotgun was at the ready should anyone doubt his seriousness.

Fifteen years later, Wilbur was Stanford’s president, and guards were stopping people, not milk. The Daily reported quarantines between campus and Palo Alto, as well as Camp Fremont, the vast Army base that had sprouted in the Foothills in preparation for the war.

Wilbur mandated nightly temperature checks for all students. Those measuring above 99.3 were isolated. The Daily offered tips like “Don’t shake hands” and “Don’t ride in crowded cars.” Fraternity houses became infirmaries. Students volunteered as nurses both on campus and at the understaffed base, where hundreds more influenza victims suffered.

Then as now, not everyone took things so seriously. Early in October, the Daily quoted a campus Navy official dismissing the wave of illness as the common flu. And even as deaths began to mount, some people still found room to joke. On October 16, the newspaper ran adjacent front-page stories that could hardly have clashed more. One announced the death of a second Stanford student due to the epidemic, the other feigned outrage that those with the illness supposedly received better food. “If it is necessary to get the Spanish influenza before you can get a good chicken dinner in the vicinity of the University, things have got to be changed, or else let’s get the influenza!”

Sullivan, Class of 1919, survived after spending two nights packed in ice and a week convalescing at Camp Fremont. He returned to campus to find junior Lorenz Hansen, a dear fraternity brother, at death’s door, and an eerie hush in so many places he’d had joyous memories. “I wonder if the place ever again will resume a normal status,” he wrote. “Nothing like it has ever hit this university in its entire history.”

He asked his fiancée to drape his fraternity pin with a black sash in mourning for Hansen and implored her to disinfect her mask three times a day.

Still, life then appears not to have been interrupted quite as much as ours now. Unable to get leave to serve as Hansen’s pallbearer, Sullivan seemed relieved. “Such things break me all up and leave me sick for a day,” he wrote. Instead he ditched his uniform for corduroys, slipped past quarantine, and got a haircut in Palo Alto, still open for business. The same day, October 21, the Daily announced four more student deaths.

AMONG THE LOST: Lorenz Hansen, a member of Stanford's SATC, had just been transferred to the aviation corps when he died of pneumonia following an attack of influenza. (Photo: Quad, 1920)

AMONG THE LOST: Lorenz Hansen, a member of Stanford's SATC, had just been transferred to the aviation corps when he died of pneumonia following an attack of influenza. (Photo: Quad, 1920)By early November, though, officials felt the worst had passed, and the campus mask requirement was lifted. On November 11, celebrations broke out at the news of the armistice ending World War I. And by Thanksgiving, Big Game football returned, ending rugby’s 13-year reign as Stanford’s marquee sport.

To many, the plague had already been vanquished. “The attack of the epidemic was met like the attack of the foe,” the Stanford Illustrated Review, the alumni publication, wrote in its November issue. “Keep cool; stand ready; aim low; go about your duties!”

Yet illness on campus continued, albeit in smaller numbers. The last recorded death was that of Henry Lewin Cannon, a 47-year-old associate professor of English history who succumbed on January 5, 1919. Thereafter, the term Spanish influenza mostly drops from the Daily’s archives.

A comprehensive list of victims is hard to come by. The Stanford Illustrated Review identifies 10 dead undergrads in an honor roll that November. The president’s annual report, published the following year, indicates 12 students died—10 men and two women—but leaves them unnamed. Besides Cannon, at least one other nonstudent member of the campus community died: Charlie Meyers, the longtime campus barber, cigar purveyor, lender of last resort and much-sought student counsel.

Fourteen dead, almost all of them students. On its face, it’s a jarring total. Adjusted for the size of the student body, it’s shocking. Stanford then had 1,322 undergrads, less than one-fifth the present number.

‘I wonder if the place ever again will resume a normal status. Nothing like it has ever hit this university in its entire history.’

Rather than horror at the tally, there seems to have been a sense that Stanford got off lightly. “I think the influenza is on the wane here. There are only 109 S.A.T.C. men in the hospital,” Snedden wrote near the peak of the epidemic. “We have only had one girl & eight men die.”

Perhaps in that pre-antibiotics era, with war raging and accidents common (another Daily headline that October told of a young alumnus lost in a shipwreck), death was a more familiar presence. And certainly, the toll elsewhere may have made Stanford’s seem small. Nearly 150 died at Camp Fremont, 3,000 in San Francisco, 675,000 in the United States, and likely more than 50 million across the world.

But each death was still an explosion of grief to those close to it. A week after Hansen’s death, his only sibling, a sister, died too. A few months later, a brief appeared on the front page of the Daily. Hansen’s parents were appealing for the return of any of their son’s papers, final mementos of a life ended far too soon.

Sam Scott, formerly a senior writer at Stanford, is now based in Toronto.