Brown says we are poised to make a shift similar to when humans went from hunter-gatherers to domesticating livestock for food. It made sense then; it makes no sense now, he asserts.

“The use of animals, the food technology, is essentially completely responsible for this catastrophic collapse in global bio-diversity,” says Brown, who at 65 still runs marathons. “What people don’t realize is it’s not just that we won’t see giraffes anymore if we stay on this path. It’s that we depend on that biodiversity to keep the ecosystems and our planet healthy.”

But most people won’t give up eating what they love, Brown acknowledges, even if it is for a good cause. “That means that we just have to find a way to satisfy the demand for beef, because it is not going to go away.”

So Brown assembled a team of mostly Stanford-trained scientists and put them to work developing a meatlike product that would be good enough to satisfy even the most devoted beef eaters. The first obstacle for Impossible was to figure out how to reproduce the flavor that makes meat, well, meaty. It turns out a molecule called heme is the answer. Heme exists in both plants and animals, behaving similarly even though it is chemically different. It is heme that makes a medium-rare Impossible Burger appear to bleed, and gives off the aroma of cooked meat. The company’s scientists figured out that soy was a good primary source of heme, but soon learned that uprooting hundreds of acres of soybean plants was not environmentally or financially sustainable. So they developed a different method: injecting the DNA from soy plants into genetically engineered yeast.

Sergey Solomatin, a former Stanford postdoc in chemistry, is director of research at Impossible. He laughs at the early memory of trudging through ankle-deep dirt in Minnesota, where soybeans are a dominant crop, pulling out the plants and using a hair comb to separate the heme-containing nodules. “We ground the nodules up and brought them back and said, ‘Now make burgers,’ to the rest of the team. We had no idea.”

Finding that meaty flavor maker was a major milestone, but Impossible R&D also had to tackle texture—in short, to make its plant-based product behave like hamburger. That meant creating a ground mixture that would not crumble when cooked and that didn’t require special instructions.

‘If people want to watch their diet, exercise more and maintain a better lifestyle, that would be smart, but I wouldn’t say you necessarily have to eat less meat for better health.’

At Impossible’s high-ceilinged laboratory inside the company’s Redwood Shores, Calif., headquarters, Solomatin demonstrates a machine that measures how much force is required to bite into and chew a burger; an appealing meat replacement needs to offer similar resistance. Other technologies test the burgers for cooking behavior, juiciness and aroma (there is one room designated just for smell tests). The Impossible Burger itself is manufactured in a 68,000-square-foot plant across the Bay in Oakland, as its younger cousin, Impossible Pork, will be.

The second edition of the Impossible Burger, released in January 2019, contains 21 plant-derived ingredients. Some are unfamiliar to consumers, like the methylcellulose from the spelling bee ad. Protein comes from soy and potatoes, fat from coconut oil and sunflower oil. Binders and starches help hold the patty together so it doesn’t fall apart on the grill or in the skillet.

Many consumers cannot differentiate the Impossible Burger from a beef burger, an obvious win for the company. However, the Impossible version is more expensive than a conventional burger—it will run you $16.95 at the Counter in Palo Alto, whereas a beef burger costs $12.95—which helps explain why the company’s marketing focuses not just on taste but also on associated benefits Impossible says are inherent in a plant-based burger. Nutrition, for one.

The Health Argument

Christopher Gardner has spent more than 20 years studying diets and food patterns and their impact on humans. A professor of medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center, he isn’t ready to declare the Impossible Burger the winner in the nutrition sweepstakes. “On the health side, we just don’t know yet.”

Gardner is counting on his study dubbed SWAP-MEAT (Study with Appetizing Plant Food-Meat Eating Alternatives Trial) to shed new light on the health results of eating plant-based versus animal-based meat. Funded by an unrestricted grant from Beyond Meat, it will be ready for publication this summer. It is the first randomized study of its kind.

SWAP-MEAT is designed to investigate the effect on heart health, the gut microbiome and metabolic status when replacing the consumption of animal meat with that of plant-based meat. Participants consume specified beef products for eight weeks, then switch to plant-based meat alternatives for another eight weeks. Short-term studies like this one give investigators important clues about risk factors that can appear as early as two weeks into an altered diet. The findings will also inform future long-term studies.

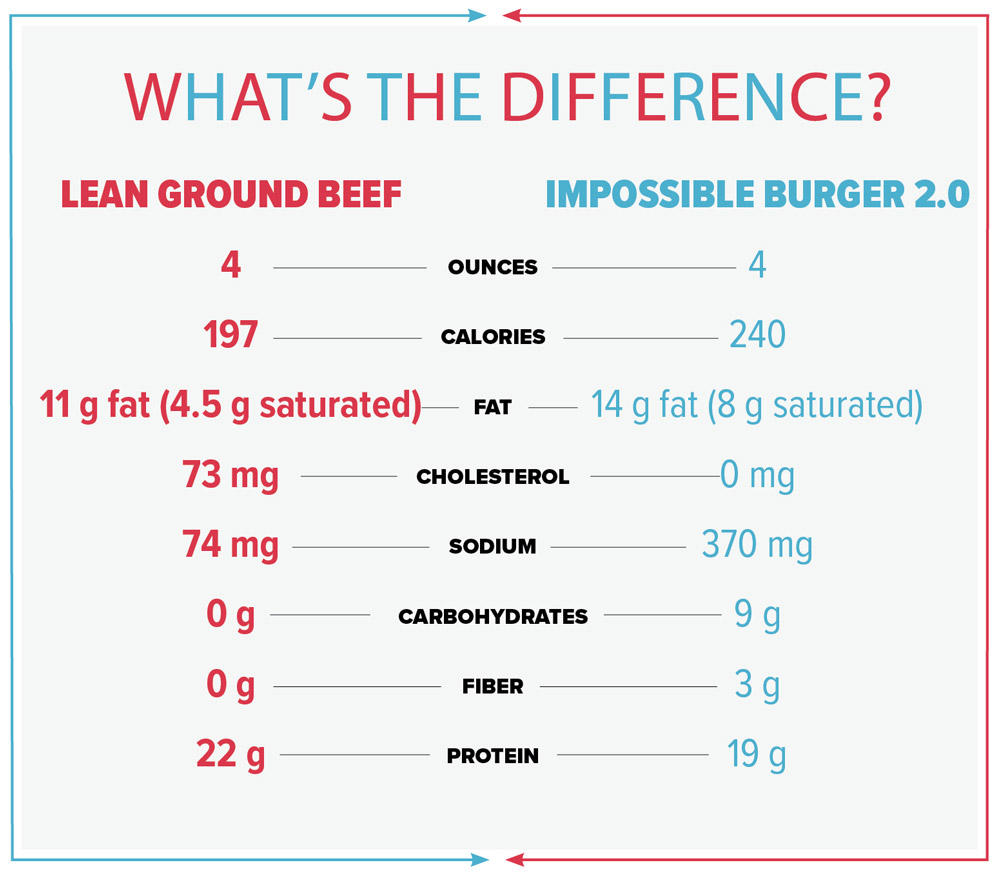

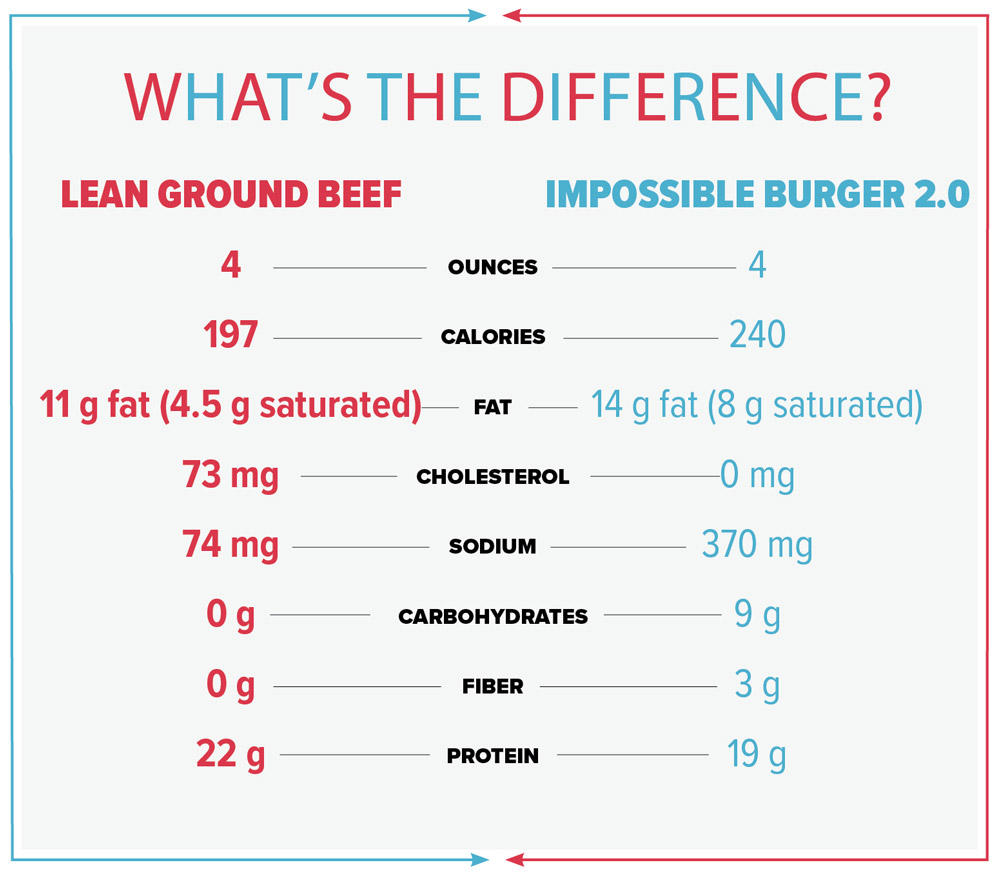

In the meantime, critics point out that plant-based burgers are highly processed, contain GMOs and have much higher sodium content than a typical beef burger. (See graphic, below.) Among the most outspoken is John Mackey, co-founder and CEO of Whole Foods Market, which carries Beyond Meat products but not yet Impossible Foods. A 2019 commentary by three Harvard researchers in the

Journal of the American Medical Association, while noting the risks of diets high in red meat, said people should also be “cautious” about the health effects of plant-based alternatives that use purified plant proteins rather than whole foods.

Others are unmoved by the “overprocessed” argument against alt-meat. Gardner points out that commercial bread has 27 ingredients. Commercially raised cows are fed antibiotics, hormones and feed additives, which end up in the beef. “Do those count as ingredients?” he asks.

WHAT'S THE DIFFERENCE?

Lean Ground

Beef

Impossible Burger 2.0

4

ounces

4

197

calories

240

11 g fat

(4.5 g saturated)

fat

14 g fat

(8 g saturated)

73 mg

cholesterol

0 mg

74 mg

sodium

370 mg

0 g

carbohydrates

9 g

0 g

fiber

3 g

22 g

protein

19 g

John Ioannidis, an epidemiologist and a co-director of the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford, says it’s too soon to jump to conclusions.

“Could there be harm from eating meat? Yes,” he says. “If people want to watch their diet, exercise more and maintain a better lifestyle, that would be smart, but I wouldn’t say you necessarily have to eat less meat for better health. We have no good data that a carnivore diet would be harmful, but our data are too thin in this regard.”

About that Planet

So if alt-meat burgers can offer a taste similar to beef but no particular nutritional benefits, why pay more for them? The answer may lie in the smaller environmental footprint of alt-meat products. Impossible Foods (and its closest competitors) boasts that it uses 75 percent less water and 95 percent less land while generating about 87 percent less greenhouse gas emissions to produce its burgers than do producers of conventional beef burgers. Come for the taste, invites Impossible in its promotions, but stay for the impact.

Much of the difference comes down to, well, cow burps. “Cows and other ruminants emit as much methane as all the oil and gas wells in the world,” says professor of earth system science Rob Jackson. “Eating plants lower on the food chain is more energy efficient and easier on the environment.”

It’s unclear exactly how harmful cows are to the planet, since comparisons of relative effects are complex and statistics can vary widely based on criteria used to evaluate them. For example, a 2019 study by the United States Department of Agriculture found that cows account for 3.3 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, compared with 50 percent from electricity production and transportation combined. However, other studies assess not only the impact of the cows themselves but also how acreage used for livestock production claims land that would otherwise provide natural carbon sinks. One such study, by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, placed the percentage of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions caused by livestock at 14.5 percent, more than half of which is attributed to cattle raising.

‘We are not anti-cow; we are pro-cow in the right circumstances, but in the vast majority of cattle facilities, we feed cows the equivalent of candy corn.’

“The impact of 93 million cows on the country is a real story not understood in terms of its depth and adversity,” says Denis Hayes, ’69, JD ’85, CEO of Seattle-based environmental nonprofit the Bullitt Foundation. (Hayes also organized the first Earth Day.) “We are seeing the devastation of cattle grazing and overgrazing playing out across the world, the overuse of pesticides, cow burps that add to methane pollution, beef contamination in the slaughterhouse, antibiotics and other contaminants in our meat, even the impact on climate change, which is the most dangerous factor.

“We are not anti-cow; we are pro-cow in the right circumstances, but in the vast majority of cattle facilities, we feed cows the equivalent of candy corn,” Hayes says, referring to the corn-based diet fed to the majority of factory-farmed beef cattle. “We are trying to make them fatter faster. It sounds wild, but our goal is to get people to start noticing what kinds of grasses beef are raised on, what kind of soil.”

Fourth-generation cattle rancher Cory Carman, ’01, couldn’t agree more. She says we don’t have to turn to lab-produced meat to protect the environment.

It was the feedlots she’d see driving back and forth from her home in Oregon to Stanford that inspired Carman to return there and focus on ranching practices that were regenerative, humane and financially viable. “I came back [from college] determined to raise grass-fed beef,” she recalls. “I wanted to answer the question, ‘How can you raise cattle in a way that doesn’t harm the environment?’ We are doing that.”

Carman says that by disturbing the soil with their hooves and fertilizing it with their manure, cattle that eat grass promote new growth, contributing to soil health and carbon sequestration. “Instead of talking about how to achieve that potential, we’re often starting from a place of cattle being a source of methane and thus beef is inherently bad,” she says. “When we draw a circle around an entire system and say, ‘Oh, man, cattle emit methane, therefore we should not have any cattle,’ that is the wrong approach.”

Raising and processing 100 percent grass-fed cattle is not easy, though, and it’s more expensive than raising a large number of cattle in a massive feedlot, where economies of scale provide an advantage. Moreover, Carman Ranch keeps its animals munching on highly curated grasses for up to three years before turning them into steaks and burgers, whereas a corn-fed

cow is fattened up quickly and slaughtered at 18 months.

Carman thinks there’s a place in the future for beef as a luxury garnish, an artisanal product that people are willing to pay for.

Have We Reached Peak Beef?

A Gallup poll released in January showed that more than 40 percent of Americans have tried plant-based meat products, while 30 percent still say they’re “not familiar at all” with the products. Sales of plant-based meat could reach $1 billion in 2020, the Good Food Institute projects. Ninety percent of those using plant-based products are not vegetarian or vegan, says a report from the NPD Group, a market research firm that studies consumer trends.

An article in the

Atlantic predicted that beef eating may peak in 2020, not because people don’t like beef anymore, or even because they are being environmentally aware, but because there are so many innovative options with which to replace it. And the alt-meat category will continue to grow. The newest aspirant, Berkeley-based Memphis Meats, is developing a product called cell-based meat—essentially animal flesh grown in a lab. “We want to create a scalable and sustainable way to bring meat to the plate so we can keep eating what we love,” says Steve Myrick, ’05, vice president of operations for Memphis Meats.

“It’s entirely possible to produce foods that deliver the same value and pleasure to consumers, with a tiny fraction of the environmental impact,” says Impossible Foods’ Brown. “It’s up to us to figure out how to do that and make great products. Then we have to compete in the marketplace. If we succeed, we would be taking that business away from the incumbent industry so that there’s no economic incentive to continue.”

Brown’s zealous advocacy could leave the impression that he doesn’t care about the people who work in the beef industry, but that’s not true, he says. “When you replaced an incandescent bulb with an LED, it wasn’t because you hate coal miners,” he says. The shift, Brown predicts, could lead to better, safer, higher-paid jobs with crops, not cows.

That may be a while. The market share currently represented by plant-based beef is less than 1 percent. As consumers get more information and experience with alternatives to conventional factory-farmed beef, the latter industry may contract, but how soon and how far is anyone’s guess. For now, the traditional hamburger reigns. Will it coexist with its plant-based rivals? Not if Brown has anything to do with it. He wants total victory.

“My goal was not to be in the food industry, not to start a food company and not to work on plant-based beef. It was to take down the animal-based food industry as quickly as possible.”