First-gen, Low Income and Claiming a Community

How FLI students are transforming the university for everyone.

When Dereca Blackmon arrived on the Farm as a freshman, she felt a remarkable sense of belonging. “This was the first place where I was not just the smart girl and not just the black girl. I was in this community of all these people that had had these experiences, just like me, of being the only one.”

Blackmon, ’91, plunged into life at Stanford. She majored in history, joined the Delta Sigma Theta sorority and worked with other members of the Black Student Union (BSU) to advocate a fundamental transformation of the university’s Western Culture curriculum. “We had been building a strong community that I felt just so blessed to be a part of,” she says. “Seeing that community activated and feeling empowered here was such a huge moment for me.”

But while Blackmon seamlessly wove herself into BSU activities, she longed for an additional type of community support. There was something she couldn’t easily talk about, even with her large network of friends: She had grown up in a low-income household.

“Even with all the support that I felt at Stanford and absolutely loving it here, without the explicit support for the low-income aspect of my identity, I struggled,” Blackmon says. “There was so much stereotype and stigma about it that a lot of folks carried a lot of shame and fear coming from that background. I was homeless as a student for a quarter here and no one knew.”

Stanford has been enrolling first-generation and low-income students since it opened as a tuition-free institution in 1891. The difference today is that these students are coming together as a community with a common identity, a name (FLI, which is pronounced “fly” and stands for first-generation and/or low-income) and a sense of purpose. In 2011, Stanford created the Diversity and First-Gen (DGen) Office, which recently split into the Inclusion and Diversity Education (IDE) Office and the FLI Office. The FLI Office serves as a resource hub and gathering place, offering orientation activities, funds for hardships or academic opportunities, mentorship, “FLamily” meals and more.

“Our students persist and graduate at very similar rates to the rest of the population at Stanford and they do just about as well academically,” says Blackmon, who has directed the DGen Office since 2015 and is now the assistant vice provost and executive director of the IDE Office. “But what the research shows is that what they have to endure to make those achievements is additional stress.”

The FLI Office aims to mitigate that stress, and one way to do that is to ensure that its students feel empowered. Increasingly, FLI students are designing programs that provide the kind of support they most crave—and often, their creations benefit the student body at large. Meet three who are doing just that.

Were you FLI at Stanford (even if it wasn’t called that back then)?

Share your experiences with us >

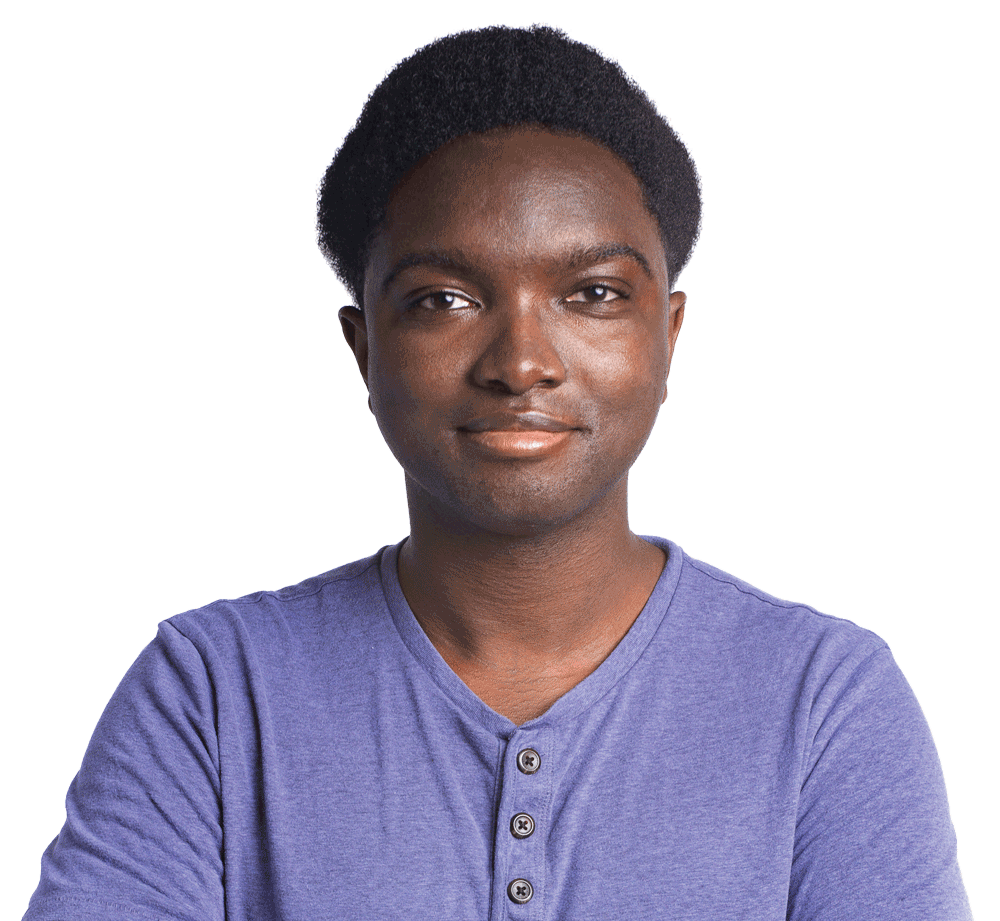

Chris Middleton, ’16

“Very early on in freshman year, we were going out to dinner on University [Ave.] a lot, and at one point I just remember saying, ‘Look, guys, I have spent more on dinner in this week than I plan to spend this month. I can’t afford to do this.’

“For a lot of us, we are not working just to support ourselves; we’re working to help support our families.

“The first time I arrived on campus, everyone else already seemed to know what everything meant. There’s this feeling of moving into a dorm where everyone knew the things that you were supposed to bring, knew all the gadgets and carry-ons to make life convenient, and I didn’t have any of those things.

“When you’re a first-gen student, you kind of buy into that idea of the American Dream in the sense that if I do all these things, there will be no more problems—like, I will have made it and it’s a permanent thing—and I think, from my experiences so far, I’ve learned that it’s very fragile.

“I had the opportunity to work on establishing Mind Over Money, which is the university’s financial literacy program. And in doing so, in taking something that was innovative, that was focused on the aspects of our identity, we were able to create something that helps all students. It turns out that a lot of students had questions around financial responsibility.”

Jessica Zhang Mi, ’21

“Both of my parents weren’t around to help me apply for college or get ready with my tests, and all of that was what I had to navigate on my own.

“[My] being in the foster care system is the most defining aspect of my FLI identity. I think a big component of that is not really having the support of your parents when you’re applying for college or not knowing what to expect when you come to Stanford.

“Although my identity is not specifically defined within first-generation and low-income, I have still found community with other FLI students. That goes to show the huge range of experiences of people who identify as FLI. I think the FLI identity is very much characterized by resilience and independence and being strong.

“We are working on this new group called Fostering Connections, which is open to all students, and the general theme is the lack of a sense of home. I hope that Fostering Connections will grow to be a big community of students and allies so that students who have been in foster care, who have been homeless, and who have been in nontraditional family backgrounds can see that this program is there for them, because that was the hope that I had when I came here. I’m hoping for us to all create a home for each other.”

Jorge Cueto, ’16, MS ’18

“I wasn’t familiar with the concept of office hours. And, actually, [in] my first couple of classes I struggled because I tried to figure things out just on my own.

“It felt like everything that I was doing, every test that I was taking, every homework assignment, was all for the cause of supporting my family.

“Not a lot of people from my community come to Stanford. So everyone’s looking at me like, ‘He’s the one that’s going to make it out; he’s the one that’s going to represent us.’

“[The DGen Office] made me feel like, yes, I have a place in this campus. I belong here. The administration acknowledges my existence, my identity as being the first in my family to go to college, my identity as someone who comes from poverty and is now being thrust into this world that is primarily dominated by people from wealthier backgrounds.

“I was able to connect with people who had similar academic interests, but they actually couldn’t really help me because they came from families that had gone to prestigious schools for generations and they didn’t have to worry about how to get money to buy textbooks. With FLAN [FLI Alumni Network], what we’re trying to do is make it really easy for alums to provide mentorship and also create this community in which we’re able to come together even after we leave Stanford.”