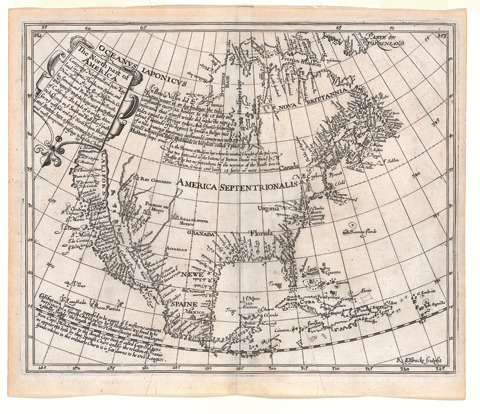

It was one of the biggest goofs in the history of cartography—yet it persisted for more than a century. A new Stanford Libraries acquisition of 800 maps from collector Glen McLaughlin tells the story: California was widely depicted as an island from about 1622 until the mid-18th century.

The misconception harks back to 1510 and the publication of Spanish author Garci Rodríguez de Mantalvo's popular novel of chivalry, Las Sergas de Esplandían. It told of a mythical island called California populated by exotic black warrior-women and ruled by the Amazonian Queen Califia, backed by a trained aerial defense force of man-eating griffins. (The island's gold deposits made it worth risking a raid.) Miguel de Cervantes ridiculed the story in Don Quixote, but the legend lived on when early explorers gave a newfound West Coast territory the fictional island's name. But what had the explorer found? An island or a chunk of the mainland?

The earliest printed maps, produced from Spanish expeditions of the 1530s and 1540s onward, corrected the myth by showing a continuous coastline. That was hardly the final verdict, however.

A Carmelite friar, Antonio de la Ascensíon, accompanied Sebastian Vizcaíno on his West Coast expedition of 1602-03 and wrote an account of the trip. About 1620, the friar apparently drew a map depicting California as an island and dispatched it back to Spain. But Dutch pirates captured the ship en route and diverted the charts to Amsterdam. Such maps were a hot commodity; Spain's were a coveted state secret kept under lock and key, making them a target for theft and plagiarism.

The Dutch subsequently published two title-page maps in 1622 in which California drifted in the Pacific. It was flat-topped and shaped rather like a carrot.

England was drawn into this error when mathematician Henry Briggs wrote of seeing a map in London, brought from Holland, showing California as an island. His article was republished with a map in 1625. Briggs's map quickly became a model for others, and soon nearly all European cartographers followed suit. California had become an island again, as McLaughlin's 800 maps attest.

The Jesuit friar Eusebio Kino was the first to offer proof against the island theory, using his 1701 map, printed in Paris in 1705. He wasn't believed; the matter wasn't settled until 1747, when King Ferdinand VI of Spain issued a royal decree that stated, "California is not an island."

The McLaughlin collection includes printed maps, celestial charts, title pages and frontispieces, rare Asian maps of the island, and a Dutch silver medal bearing a map of California as an island. "It's the most complete private collection that exists, I'm pretty sure of that," says Julie Sweetkind-Singer, head librarian of Stanford's Branner Earth Sciences Library and Map Collections. She worked as McLaughlin's map librarian before coming to Stanford in 2000.

Stanford Libraries started scanning the rare maps in 2008, and McLaughlin began to think about a permanent home for the collection: It ought to stay in California, and it should stay together as a corpus. Stanford seemed the inevitable place. For Sweetkind-Singer, the work "is an extension of the idea we had a dozen years ago—making all his work available to everyone. It's a nice closing of the circle."

McLaughlin began collecting maps more than 30 years ago, but the California as an Island collection was special. "It captures people's imagination," says Sweetkind-Singer. "Obviously, it captured his."

Cynthia Haven is associate director of communications for Stanford University Libraries.