What's the Shark Equivalent of Burning Man?

Something is drawing this marine predator to a particular gathering spot in

the

Pacific.

May 21, 2018

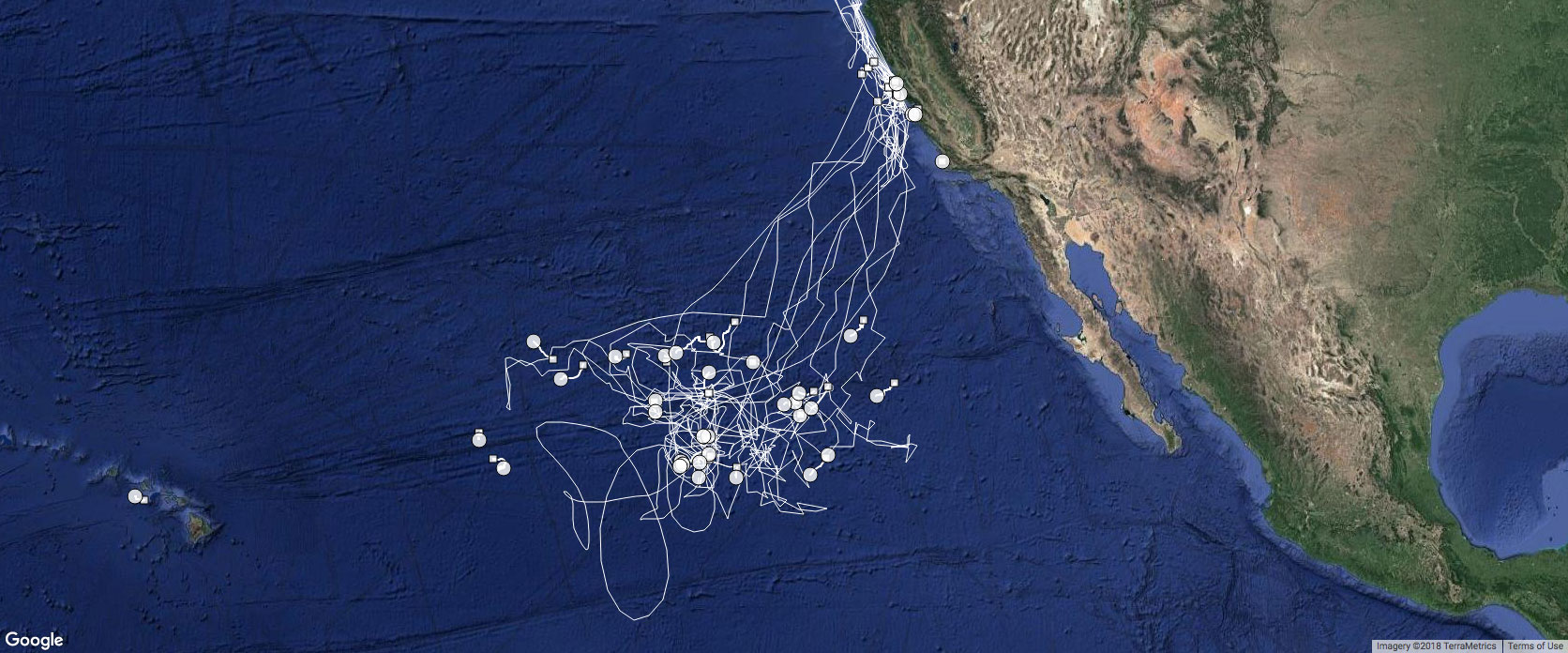

Expedition data shows the voyages of sharks on their way to the

so-called

White Shark Café.

This satellite tag was attached to a 15-foot male white shark

last November. Since then, it has been collecting depth, temperature and light data every one to five seconds.

It was programmed to release itself during the team's expedition to the White Shark Café.

Photos by SOI/Monika Naranjo Gonzalez