Bill Dement knew he was in trouble when he felt his eyelids begin to droop. He shook his head and tried to concentrate on what the professor was saying about reproductive endocrinology. But despite his best efforts, the room grew fuzzy and dim as his eyes slowly closed. Some moments later, his head jerked up from where it had fallen to his chest. He again willed himself with all his might to stay awake, but it was no use; sweet darkness enveloped him. Finally, feeling the sharp jab of his neighbor's elbow to his arm, Dement opened his eyes to see the professor frowning at him and pointing to the door.

Six decades on, the man considered the "father of sleep medicine" still remembers the embarrassment he felt as a medical student being kicked out of class for drowsiness he couldn't control. Perhaps that's why undergraduates in his perennially popular Sleep and Dreams course get rewarded, rather than rebuked, for dozing off—provided they stand up and shout "Drowsiness is red alert!" when Dement wakes them with a practiced shot from his trusty water pistol. These four words have become Dement's mantra: A reminder to all that when sleep beckons, it's time to obey, particularly in situations where an accidental catnap could have devastating consequences. "It's fundamentally about respect for sleep," he says.

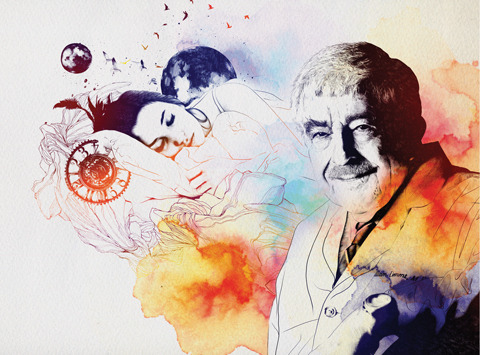

Dement's early experiments at the University of Chicago in the 1950s revealed the structure of the sleep cycle, documented the connection between REM sleep and dreams, and proved that the sleeping brain was worthy of serious scientific study. He joined the department of psychiatry at the School of Medicine in 1963, shortly after it relocated from San Francisco to the Farm, and in 1970 founded the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic, the first of its kind. In a tireless campaign to educate the public about the vital importance of healthy sleep, he has written numerous books, lobbied Congress and crisscrossed the country to speak on the issue. But perhaps his most profound impact has been as the beloved professor of Sleep and Dreams.

In Mark Rosekind's day, the two most popular classes were Human Sexuality, taught by Herant Katchadourian, and Sleep and Dreams. "You know, sex and sleep—80 percent of all undergraduates had those on their transcripts when they graduated," says Rosekind, '77. On the order of 20,000 Stanford students have taken the course since Dement taught it for the first time in 1971. Now, as then, students remain eager to learn about the science of sleep from the man who helped create it. Those enrolled last spring say it has become "part of the Stanford experience"—"a legend."

Invisible at Night

While studying to become a psychoanalyst at the University of Chicago, Dement became enchanted by Freud's theories that dreams were the key to unlocking the secrets of the unconscious mind. In 1953, after hearing a lecture by Nathaniel Kleitman, the Russian-born pioneer of sleep science, he had banged on the older scientist's door, begging to join his lab. Kleitman agreed to let Dement assist his graduate student, Eugene Aserinsky, who had just discovered the phenomenon of "rapid eye movements" during sleep. When Aserinsky casually mentioned an apparent connection with dreaming, "this offhand comment was more stunning than if he had just offered me a winning lottery ticket," Dement recalled in his 1999 book, The Promise of Sleep.

He began moonlighting as a sleep researcher (which may explain his struggle to stay alert in class). While a volunteer slept in the next room, electrodes pasted to his scalp and near his eyes, Dement would sit awake in the dark, silent lab, tending to the temperamental EEG machine as it sketched out jagged lines onto long reams of paper. As the subject's sleep grew deeper, the traces would synchronize into slow, large amplitude waves of activity. Then, suddenly, they would become irregular again and the readings from the electrodes by the eyes would begin to spike. Dement would venture into the room to shine a flashlight on the volunteer's face, revealing eyes shuttling quickly back and forth beneath closed lids. When he woke subjects during these episodes, they would almost always recount dramatic dreams.

Dement earned his MD in 1955, and by the time he completed his PhD in 1957 he had recorded the response of dozens of adult volunteers, as well as infants and cats, and had seen REM in every case. At the time, the scientific community viewed sleep as a fundamentally quiescent state, hardly worthy of scientific inquiry. "It was kind of like you were invisible at night," Dement recalls. But he showed that in addition to the hallmark eye movements, REM sleep is accompanied by intense brain activity and elevated heart rate and breathing. By these measures, dreaming could easily be mistaken for alert consciousness—except that the eyes are closed and the body is typically immobilized in a unique state of muscle paralysis (presumably to prevent injury from physically acting out our dreams). REM sleep appeared to Dement to be as distinct from the rest of sleep as sleep itself is from wakefulness.

To relieve the tedium of sitting up all night taking notes, Dement developed techniques to continuously record brain activity, eye movements and muscle contraction. This allowed him to map out the standard 90-minute cycle—four stages of slow-wave sleep followed by a period of REM—that slumberers traverse four to five times each night. He discovered that we spend progressively longer periods in REM as the night progresses, totaling up to two hours per night. Prior to this, says Dement, "most people thought dreams were instantaneous. Nobody had any idea that you had this totally different stage of sleep."

The Birth of Sleep Medicine

Doctors had long considered sleep to be universally beneficial, a pure and healing state where the physician had no place. But by the early 1960s, the techniques Dement had pioneered for the study of dreams began to reveal that sleep was as subject to disease as any other biological function. Dement had moved to New York to complete his clinical internship and for several years ran a sleep laboratory in a large apartment overlooking the Hudson River in Manhattan. It was during this period that he, along with colleagues in New York and Chicago, discovered that narcolepsy—a condition characterized by sudden, involuntary lapses into sleep—involved clear abnormalities of REM sleep. It was one of the only times in his long career Dement can remember making a major discovery in a matter of seconds.

When he arrived at Stanford, he set aside most of his research on dreams and shifted his focus to pathologies that affect sleep quality—and to the importance of optimal sleep in our daily lives. "It wasn't until we realized there were sleep disorders," he says, that people started paying attention to sleep research. In 1970, he founded the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic, a center dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of these maladies. The clinic was soon inundated by patients complaining of extreme daytime sleepiness due not to narcolepsy or insomnia, but to a recently discovered disorder, sleep apnea, in which the patient's airway would collapse during sleep, causing him to wake gasping for air hundreds of times each night.

When he arrived at Stanford, he set aside most of his research on dreams and shifted his focus to pathologies that affect sleep quality—and to the importance of optimal sleep in our daily lives. "It wasn't until we realized there were sleep disorders," he says, that people started paying attention to sleep research. In 1970, he founded the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic, a center dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of these maladies. The clinic was soon inundated by patients complaining of extreme daytime sleepiness due not to narcolepsy or insomnia, but to a recently discovered disorder, sleep apnea, in which the patient's airway would collapse during sleep, causing him to wake gasping for air hundreds of times each night.

Galvanized by the unexpected prevalence of undiagnosed sleep disorders, Dement spent the next decade working feverishly to raise the profile of sleep medicine as a clinical field. Before long, similar clinics were springing up all over the country, "and they were finding the same thing," Dement says. Still, it wasn't until 1993 that the first long-term epidemiological study found that 24 percent of men and 9 percent of women suffer from sleep apnea. Research at the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic and elsewhere has found strong correlations between sleep apnea and obesity, high blood pressure and heart disease, America's leading cause of death.

Balancing on a Rail

Standing on the deck of Jerry House, overlooking the grassy expanse of Lake Lagunita, Dement gazes out wistfully and wonders aloud whether salamanders still live behind the house as they did in the '70s and '80s, when the dormitory was still called Lambda Nu. Then he turns and asks if I'd heard about the recent crash on Highway 5 north of San Francisco, in which a FedEx truck slammed into a school bus, killing both drivers and eight high school students. Dement is grimly certain that the FedEx driver had fallen asleep at the wheel. He has been sounding the alarm about the dangers of drowsiness and sleep deprivation for decades, and traces his crusade to this quiet spot on the shores of Lake Lag.

Between 1976 and 1985, Lambda Nu was the site of the Stanford Summer Sleep Camp, the first long-term study of sleep in adolescents. Led by Dement's graduate student Mary Carskadon, PhD '79, counselors—standout students from the previous year's Sleep and Dreams class—would record the campers' sleep and then test their energy and alertness throughout the following day. The campers would play volleyball after lunch, go bowling in the afternoons, and, when it was their turn to be sleep-deprived, play games and talk late into the night.

The ability to monitor campers' sleep and daytime alertness objectively over multiple days, along with ensuing studies in adults and elderly subjects, revealed the fundamental biological forces governing daytime alertness. Our circadian clocks produce two peaks of alertness: in the morning and late afternoon, with a dip just after noon (around the time many cultures take a siesta). But another factor is sleep need, a pressure to go to sleep that builds up as long as we are awake. Sleep need is measured in the brain by levels of the metabolite adenosine, which can be temporarily masked by caffeine to make us feel more alert. A full night's sleep resets the sleep need that has built up during the day, allowing us to start fresh the next morning.

The ability to monitor campers' sleep and daytime alertness objectively over multiple days, along with ensuing studies in adults and elderly subjects, revealed the fundamental biological forces governing daytime alertness. Our circadian clocks produce two peaks of alertness: in the morning and late afternoon, with a dip just after noon (around the time many cultures take a siesta). But another factor is sleep need, a pressure to go to sleep that builds up as long as we are awake. Sleep need is measured in the brain by levels of the metabolite adenosine, which can be temporarily masked by caffeine to make us feel more alert. A full night's sleep resets the sleep need that has built up during the day, allowing us to start fresh the next morning.

The scientific jury is still out on what is the "right" amount of sleep for humans generally—some individuals may need only six to seven hours a night, while others may need nine or more. The only real way to know how much sleep you need, Dement says, is by the way you feel the next day. "There's some amount of sleep where you feel pretty wide awake and alert all day long." His recommendation: "Sleep until you can't sleep any more."

The Sleep Camp results also showed that when we sleep less than a full night, our unresolved sleep need persists as sleep debt. This debt can accumulate over multiple nights of partial sleep deprivation to affect alertness as badly as pulling an all-nighter—impairing judgment, reducing reaction times and negatively affecting mood. Long-term sleep deprivation has since been linked to increased risk of stress-related illness and major depression as well as heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes and early death. Carskadon, now a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University's medical school, compares sleep deprivation to walking at the edge of a cliff on a path that gets narrower and narrower until you are balancing on a rail. Sleep usually gives you a healthy buffer zone, she says, but when you're seriously sleep-deprived, "if the wind blows, you've got nothing. Take one false step, and you're done."

"When I realized that sleep loss accumulated," Dement says, "it was clear that most people don't sleep the amount that would allow them to be wide awake for the entire day." For years he had seen stories in the news about inexplicable crashes and accidents that he thought might be related to people falling asleep at the wheel. In the late 1970s he began running a clipping service to keep track of them all. He realized that the role of fatigue in many of these incidents simply wasn't being reported. Even now, he complains, police officers investigating a car crash rarely ask about drowsiness; if there's a trace of alcohol, it's put down as alcohol-related, even though lack of sleep exacerbates the impairing effects of inebriation. Investigations of major disasters such the Three Mile Island meltdown, the Exxon Valdez spill and the Challenger shuttle explosion all listed sleep deprivation as a major contributing factor, but Dement worries that this aspect of these tragedies has not reached public consciousness.

Dement started taking his concern about the prevalence of drowsiness and sleep disorders to the halls of Washington, but found the process too slow. He soon discovered that if he scheduled a meeting with one member of Congress, "I could go down the hall in the House of Representatives, just walk into every office, and somebody would talk to me." In 1988, Congress created the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research, led by Dement, to survey the nation's sleep health. "The national commission was huge," says Rosekind, now a member of the National Transportation Safety Board. "They literally went to different cities and held panels, and had people with sleep disorders and truck drivers and nurses and everybody talk about [their concerns]. . . . Nobody had ever done anything like that before—to shine a light on the full range of sleep issues that affected our lives."

The commission's 1992 report, Wake Up America! A National Sleep Alert, estimated that as a nation we were sleeping 20 percent less than we had a century before, that 40 million Americans suffered from chronic sleep disorders, and that sleepiness had become a major problem on the nation's highways, in schools and in the workplace. More recent estimates have placed the annual number of casualties caused by drowsy driving at 40,000 per year, and the number of shift workers at heightened risk for sleep deprivation at 20 percent of the U.S. workforce. In response to the commission's report, Congress established the National Center on Sleep Disorders Research at the National Institutes of Health to help fund and coordinate sleep research nationwide.

Season of All Natures

Since his work leading the national commission, Dement has remained focused on how best to educate the world about sleep, making it on par with exercise and nutrition as part of a healthy lifestyle. Students in Sleep and Dreams learn about the sleep cycle, sleep debt and circadian rhythms of alertness, about narcolepsy, apnea and insomnia, and certainly about dreams. But "Drowsiness is red alert" has become a major theme of the class. Above all, says Dement, he wants his students "to learn facts of sleep that are necessary to stay alive." To remember that "if you're driving or doing anything hazardous, and you feel like your eyes want to close or your eyelids are heavy, that's it, that's red alert—get out of that hazardous situation."

Since his work leading the national commission, Dement has remained focused on how best to educate the world about sleep, making it on par with exercise and nutrition as part of a healthy lifestyle. Students in Sleep and Dreams learn about the sleep cycle, sleep debt and circadian rhythms of alertness, about narcolepsy, apnea and insomnia, and certainly about dreams. But "Drowsiness is red alert" has become a major theme of the class. Above all, says Dement, he wants his students "to learn facts of sleep that are necessary to stay alive." To remember that "if you're driving or doing anything hazardous, and you feel like your eyes want to close or your eyelids are heavy, that's it, that's red alert—get out of that hazardous situation."

Dement has lobbied nationally and locally for improved education about sleep in high schools and medical schools, for reduced hours for medical residents and for later start times for high schoolers. Some of these efforts have begun to pay off, though not as many or as quickly as he hoped. In 2003, the ACGME, the trade association that accredits residency programs, passed new rules limiting working hours for residents to 80 hours a week. And new federal rules requiring more frequent rest periods for truckers and airline pilots went into effect in 2013 and 2014, respectively.

In recent years, Dement also has focused his research at the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic on the positive effects of eliminating sleep debt. In a 2004 study, he asked 15 undergraduates to extend their sleep as much as possible for several weeks and found significant improvements in their daytime alertness, reaction times and mood. A 2011 study found that basketball players who slept an average of eight and a half hours each night for five to seven weeks (compared with a baseline average of six hours and 40 minutes per night) increased their sprint speed and shooting accuracy as well as general reaction times, alertness and overall sense of well-being.

These studies add to a growing body of literature showing how much better we all might feel if we could eliminate sleep debt from our lives. This message may finally be getting through. Partway into the first session of Sleep and Dreams this past winter quarter, Dement scans the room, water pistol at the ready. "Not a single person is sleeping," he announces, with a hint of disappointment. Then he shouts "That's wonderful!" and launches into a description of sleep spindles, a feature of brain waveforms that indicate a person is sleeping. All too soon, one of his TAs waves to get his attention. "Class is over?" Dement asks, his eyebrows rising. "I'm just getting started!"

Nicholas Weiler, PhD '14, is a student in the science communication program at UC-Santa Cruz.